2. Avery

“They’re just kids, Avery.” Director Murray leaned back in her chair, the wicker creaking as her weight settled. “Treat them like you would any other band geek battling acne and raging hormones.”

“I do!” Avery leaned forward, wringing her hands together in her lap. “I mean—I’m trying to. I’ve just never been around this many mons-” At Director Murray’s raised eyebrow, Avery caught herself. “Inhumans.”

“See? You’re getting better already.”

“But that’s the problem, Director Murray,” she whined. “I keep slipping and offending them, and then I second-guess myself for the rest of the class. How am I an effective teacher if I can’t even speak appropriately to them?”

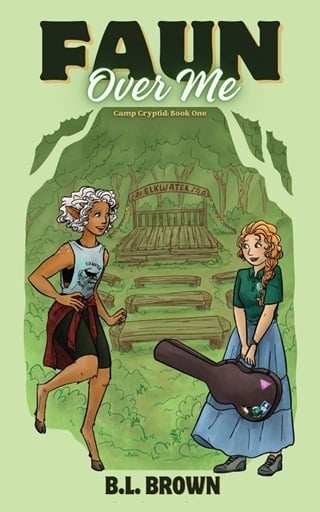

“Well, first of all, stop thinking of our campers as a ‘them.’ We’re an ‘Us’ at Elkwater Music Camp.” Director Murray spun the gold ring on her finger, frowning slightly. “Second of all, you’re an incredible teacher and an even better musician. I wouldn’t have offered you the job if you weren’t; and third, for the love of God, stop calling me Director Murray.”

Avery opened her mouth, closed it, then muttered, “I still don’t know why you hired me.”

“Because you were the best-qualified candidate.” Director Murray’s frown deepened. She sat forward and placed her elbows on the desk between them, hazel eyes pinned on Avery. “Because you applied.”

“But—”

“No more buts, Avery,” she sighed. “You graduated from the composition track at Messiah. You’re a poly-instrumentalist who spent the last four summers counseling at a band camp in Virginia, which, come on. You couldn’t have applied to work for me earlier?” Avery opened her mouth to argue, but at the director’s pointed look, she decided the question was rhetorical. “I should probably be asking why you finally did decide to apply for a job here.”

Avery’s only response was a quiet squeak.

“You knew we were an integrated camp when you applied, Avery, and that told me you were the right person for the job.” Director Murray smiled and eased back, gesturing to the framed pictures decorating the walls. Happy teens grinned in one photograph with their arms slung around wolven and naga. In another, gnomes sat on the shoulders of human boys, tiny fingers poised on piccolos and flutes. A group of musicians—furred, scaled, and fleshy—perched on logs and tree stumps around a fire, mouths frozen open in song. Photograph after photograph of musicians of multiple species marching in a field, collaborating on music, and grinning in the dining hall. So unlike the childhood she had known and entirely the one she had desperately wanted. “Stop being so hard on yourself and focus on what’s most important: these kids are here to learn. From you.”

Avery smoothed the front of her skirt and scuffed the toe of her white tennis shoe along the worn woven rug, feeling the weight of Director Murray’s gaze on her. “I’m just scared that I’ll—”

“Ah.” The director stood, setting palms on the desk and leaning over the paperwork she had been reviewing when Avery knocked on her door. “There it is.” Her eyes narrowed, darting over Avery in quick assessment. “That’s your father talking, Payne. Not you.”

“I—”

“There’s nothing to be afraid of in this camp. Everyone here earned their spot through talent and hard work. It’s what we all have in common. Think about that, yeah? These kids earned a place, just like you earned your job as my Assistant Director.”

Avery dropped her eyes to her lap, staring at the grass stains on the knees of her skirt and biting her lips to keep from blurting the truth: that she’d only applied for the job after an argument with her dad. That she was piggybacking on Director Murray’s reputation for churning out top-tier musicians and using this job to get a spot in Carnegie Mellon’s graduate program. That she was using this camp and the director’s goodwill to further her own aims, and was using this summer to live the life she never got to. That she couldn’t sleep at night because of the guilt and fumbled chords during the day because she was drowning under the pressure. That the storm last night had seemed to mimic her own inner turmoil until she thought she was going to burst. That she—

“I know you grew up in an area that was … affluent,” Director Murray continued. “I did, too; I know how close-minded it can get, but you’re here, regardless of your reasons for applying. That matters.”

Avery swiped the back of her hand under her nose, blinking tears away before raising her head. Director Murray had resumed her seat, fingers laced on the desk. Though her face was calm, her mouth closed but soft, there was a tension in her arms and shoulders. From her years spent as a camper, a counselor, assistant director, and finally director, Director Murray was tanned and lean, toned in the way of an Appalachian thru-hiker. She kept her shaggy pixie cut swept back from her face, the ends of the short style bronzed from the sun. Small lines clung to the corners of her eyes and mouth, earned from summers on the field and evenings spent laughing and smiling.

Avery wondered what it was like to be so carefree when surrounded by so many mons—no. Inhumans.

Back home, in Harrisburg, it wasn’t exactly rare to see them, but just as Director Murray said, she had grown up in an affluent area, surrounded by people who looked, spoke, and existed like her: human, white, and Christian.

Elkwater Music Camp was the furthest from home Avery had ever been, not in terms of distance but in lifestyle and culture. Messiah wasn’t an integrated campus, and whenever she traveled to Philly or New York with her family, they were ushered from their car to the hotel, paraded about like a Christian Right Von Trapp Family, and ushered out of sight. The most diversity Avery had ever experienced was from playing softball as a teenager. Even then, the team was entirely human, as were those of the other private schools they played against.

Sure, she had seen inhumans. She wasn’t a flower in the attic or anything weird like that. It was just that people like her didn’t associate with inhumans like them … until now.

“I want to be here,” she said. “I want this job, I want to teach these kids, but I—”

“There’s those buts again,” Director Murray smiled. “The campers have only been here for two weeks, and you did great during onboarding with the counselors and staff. Take it each day at a time, pick a different kid in each class, and give them some special attention. Learn how the unique qualities they each bring can help them excel in music, and you’ll have done your job.”

Avery exhaled, blowing a stream of air at a curling wisp of her hair. “Okay.”

“And maybe sit with the other counselors at dinner?” Director Murray added. Avery straightened, a tendon in her neck pinching. “It hasn’t gone unnoticed …”

“They don’t want to sit with me.”

“Says who?”

“I—no one.” She dropped back in her chair, arms crossed. “But—”

“No more buts, Avery, Jesus.” Avery flinched, and Director Murray dropped her head back, groaning. “Ugh, sorry. Look.” she rose and stepped around the desk, cuffing Avery on the shoulder with a loose fist. “I know this is a lot, and I respect how you addressed this in your interview, but don’t give up after two weeks. A lot of these kids and counselors have grown up in this camp. I marched at OSU with Nurse Almaden, and your roommate has been a counselor here for as long as I can remember. We’ve got you at a disadvantage, but it’s not one you can’t overcome. You’re here, and you’re coming to me when you need to talk it through. Keep doing that, and next summer this’ll be as common as a chord progression in C.”

Avery huffed. “You’re saying that like you know I’m coming back next year.”

“You haven’t run screaming for the hills yet.” Director Murray smiled. “That’s a good sign.”

“There’s still twelve weeks to go,” Avery replied as she stood, adjusting her skirt. “Plenty of time.”

“There’s that can-do attitude I hired you for.” She sighed and straightened the papers on her desk. “I could use a little of that, I think.”

“Still no takers?”

Director Murray shook her head, lower lip thrust in a pout. “Not yet. My mom is gonna talk to a few of her associates in DC. Hopefully, someone will be interested in investing, but it feels like cheating.”

“How so?”

A bell rang before she could answer, the electric tone buzzing through the open window and calling the camp to breakfast. Director Murray checked her watch and tipped her head at the door, gesturing for Avery to walk with her.

“I can’t even get investors to call me back, much less answer the phone. Growing Elkwater to welcome more students feels like something I should be able to do without relying on my parents’ connections,” she said.

“It’ll happen.”

Director Murray snorted quietly and bounced her shoulder against Avery’s. “Where’s that confidence when it applies to your job performance?” Avery opened her mouth to argue, holding her tongue when Director Murray sighed and shoved her hands in her pockets. “Let’s talk about this later; if you don’t mind channeling some of that Payne knowledge, I’d like to pick your brain on how I can better approach sponsors.”

“Sure thing.” She sent her boss a weak smile.

Director Murray jogged up the stairs to the dining hall, pausing at the door when she realized Avery had not joined her. “Not hungry?” she asked, offering an easy out.

“I had cereal in my bunk,” she lied.

“Right.” Director Murray nodded and hit her with a direct stare. “I’ll see you at dinner, then.”

“See you at dinner.”

Not a request, but then again, Avery couldn’t really blame her. She was the Assistant Director. It was her job to be present and available for the campers and counselors, and she couldn’t do that by hiding in her bunk and eating alone.

“At the counselor’s table,” she added. Avery bit her lips and nodded, sagging with relief when Director Murray slipped inside the dining hall.

Embarrassed and not yet ready to be immersed in the bustle of a band camp in full swing, she took a narrow trail around the side of the dining hall, cutting onto a well-used path through the woods. Twigs, leaves, and fallen branches from the previous night’s storm cluttered the trail. Her conversation with Director Murray rambled over and over in her head as she kicked the mess aside, clearing the path for others. It helped to hear she was coming into this at a disadvantage, and yet, it didn’t. Avery was raised to do the good thing, to love thy neighbor, and all that, but nowhere in the doctrine of her congregation had they allowed space for those who weren’t her fellow man.

But being a good neighbor was about loving those around you, regardless of creed or color.

Right?

“Right. Of course, that’s right,” she muttered, hitching her skirt to swing a leg over a recently fallen tree trunk. The storm the night before had been wild, blowing in from the west without any warning. It was a wonder they hadn’t lost power in the camp, so Avery was hardly surprised to find a tree blocking the path. The sweet scent of rotting wood tickled her nose and she rubbed it with her palm, peering at the dark hollow of splintered oak and churned earth at the base of the trunk. “Why else would they be here if we weren’t supposed to share this earth with them?”

She straddled the tree, enjoying the quiet of the wood and the peace that thought brought. She could do this—get over the biases of her upbringing and be better before starting a graduate program at a fully integrated university.

Avery slid off the trunk and started down the trail feeling lighter. It all seemed so easy now that she’d argued her way out of a legalistic trap. Every living thing was on the earth for a reason that she, a single human, wasn’t in a place to question. All she had to do was accept it and be kind. Easy.

She ducked under a low branch, and a thorny bush snagged her skirt. Grumbling, she stooped and tugged at the fabric, yanking it free with a tearing sound that didn’t bode well for the fabric.

“Great. Just great.” She inspected the inch-long tear, tossing the fabric aside as she rose, took two steps, and stopped at the sight of a skinny, haggard form leaning against a tree less than six feet away.

“Hel—” the figure wheezed, raising a filthy, shaking arm. Sunlight glinted off of the tips of three trembling fingers. “Help me.”

“Ohmygosh.” Avery rushed over, stopping short when the figure lurched away from the tree and practically threw itself at her.

“It’s in the woods,” they gasped, gripping Avery’s shoulders. Sharp points pinched her skin and raised goosebumps. They drew close, blinking at her with wide and wild, coppery eyes. Mud caked their arms, masking their face and matting the curls clinging to their head. “It followed me, I ran, I—”

“Are you okay?” Avery circled her fingers around their thin wrists—they were covered in a soft, delicate down, she noticed—and gently pulled them away.

“It followed me; it’s out there. I ran as fast as I could.”

“Hey, it’s alright.” Avery raised her voice, using the “counselor tone” that worked so well on her campers. “Calm down, okay?” The creature’s pupils tightened to thin, horizontal ovals. Every muscle went taut, and they held themselves so still Avery wondered if they were breathing at all.

They weren’t a camper; she knew that much. As Assistant Director, it was part of her job to know every kid in their bunks, if not by name, then by sight, and this figure with their mud-caked clothes and soft downy fur, was neither a camper, counselor, or staff member of Elkwater Music Camp. “Where are you from?”

Those narrow pupils pulsed, and they twitched to meet Avery’s gaze. “Monongahela.”

And with a tight exhale, they collapsed.

Avery stood there, biting her lower lip and weighing her options. Nurse Almaden would be on the field this time of day, ensuring none of the wolven collapsed from heat stroke. Her roommate would be goodness knew where, and even if Avery could find her, what would Sanoya do? This wasn’t a camper; they didn’t belong here, which meant there was only one person to go to for help.

Avery turned and ran, scrambling over the tree trunk and hitching her skirt to lengthen her stride. In half the time it took to reach that part of the wood, she was back with Director Murray in tow.

“They said they ran here,” she panted, hitching forward and gripping her knee with one hand, pointing to the figure lying crumpled in the dirt with the other.

Director Murray skidded to a halt, the flush in her cheeks from their run fading as she stared down at the creature in shock. “She ran here?”

“How do you know it’s a she?” The figure was a mess, all torn clothes, mud, and twigs. If she’d learned one thing over the last month of being thrown feet-first into integration, it was that one never assumed gender. That was an easy way to earn the hatred of a skunk ape, and she was still apologizing for making that mistake by calling the camp cook, a rat-like inhuman with four arms and too many tails to count, “ma’am.”

Director Murray glanced at Avery and then crouched beside the figure, brushing matted curls away from its face. Her shocked expression eased to worry. “I just do.”

“Do you know…her?”

Director Murray tensed, working her jaw before speaking again. “Go back to camp.”

“What?”

“Go back to camp, grab Nurse Almaden, and send her to my cabin.”

“Do you want me to help—”

“Go, Avery,” Director Murray snapped, angrier than Avery had ever heard her. “Go and get the nurse; I’ll handle this.” She gathered the figure in her arms, struggling to her feet and turning to head back to camp. The creature hung limp, her head lolling and feet dangling.

No. Not feet.

Avery startled back, pressing against a tree as she tried to make sense of what she was seeing. The torn hem of filthy yoga pants gave way to delicate, lean calves covered in more mud, and where she would have expected shoes or toes, the creature’s ankle tapered into a cloven hoof.

“Avery,” Director Murray’s voice was calm and even. It was the voice she used whenever a counselor called her to a particularly rambunctious bunk after lights out. “Go get the nurse.”

Fullepub

Fullepub