Chapter 3

Merrie Monarch Festival, Hilo, Hawai‘i

Beneath the ribbed ceiling of Hilo's Edith Kanaka‘ole Stadium, the Tahitian drums pounded so loudly that the audience of three thousand felt the vibration in their seats. The announcer cried the traditional greeting: "Hookipa i nā malihini, hanohano wāhine e kāne, distinguished ladies and gentlemen, please welcome our first hālaus. From Wailuku… Tawaaa Nuuuuui!" A burst of wild applause as the first troupe of women shimmied onto the stage.

This was the Hula Kahiko event during the weeklong Merrie Monarch Festival, the most important hula competition in the Hawaiian Islands and a significant contributor to the local economy of Hilo.

As was his custom, Henry "Tako" Takayama, the stocky chief of Civil Defense in Hilo, stood at the back during the event ceremonies in his trademark aloha shirt and ready smile, shaking hands and welcoming people from all over the Big Island to the annual performance of ancient-style dances by Hawaiian hula schools. Even though his was not an elected job, he had the air of the campaigner about him, like a man who was always running for something.

His upbeat manner had served him well during his thirty years as Civil Defense chief. In that time, he had guided the community through multiple crises, among them a tsunami that wiped out a Boy Scout troop camped on a beach, the destructive hurricanes of 2014 and 2018, the lava flows from Mauna Loa and Kīlauea that took out roads and destroyed houses, and the 2021 eruption on Kīlauea that created a lava lake in a summit crater.

But few people glimpsed the tough, combative personality behind the smile. Tako was an ambitious and even ruthless civil servant with sharp elbows, fiercely protective of his position. Anyone, politician or not, trying to get something done on the east side of Hawai‘i had to go through him. No one could go around him.

In the stadium, Tako, chatting with state senator Ellen Kulani, felt the earthquake at once. So did Ellen. She looked at him and started to say something, but he cut her off with a grin and a wave of his hand.

"No big thing," he said.

But the tremor continued, and a low murmur ran through the crowd. A lot of the people here today had come from other islands and weren't used to Hilo's earthquakes, certainly not three in a row like this. The drumming stopped. The dancers dropped their arms.

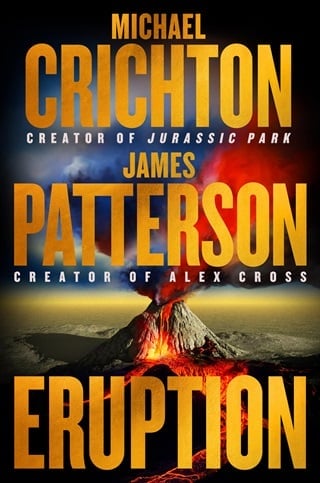

Tako Takayama had fully expected earthquakes all during the festival. A week before, he'd had lunch with MacGregor, the haole head of the volcano lab. MacGregor had taken him to the Ohana Grill, a nice place, and told him that a big eruption from Mauna Loa was coming, the first since 2022.

"Bigger than 1984," MacGregor said. "Maybe the biggest in a hundred years."

"You have my attention," Tako said.

"HVO is constantly monitoring seismic imaging," MacGregor said. "The latest shows increased activity, including a large volume of magma moving into the volcano."

At that point it became Tako's job to schedule a press conference, which he did, for later today. He'd done it reluctantly, though. Tako thought that an eruption on the north side of the volcano wouldn't matter a damn to anybody in town. They'd have better sunsets for a while, the good life would go on, and all would once again be right in Tako's world.

But he was a cautious man who considered every possibility, starting with the ones that affected him. He didn't want this eruption to be a surprise or for people to think he had been caught off guard.

Eventually, being a practical man, Tako Takayama found a way to turn this situation to his advantage. He'd made a few calls.

But now he was in the middle of this awkward moment in the auditorium—drums silent, dancing stopped, audience restless. Tako nodded at Billy Malaki, the master of ceremonies, who was standing at the edge of the stage; Tako had already told him what to do.

Billy grabbed the microphone and said with a big laugh, "Heya, even Madame Pele gives her blessings to our festival! Her own hula! She got rhythm, ya!"

The audience laughed and burst into applause. Mentioning the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes was exactly the right touch. The tremors subsided, and Tako relaxed and turned back with a smile to Ellen Kulani.

"So," he said, "where were we?"

He was acting as if he himself had ordered the tremors to stop, as if even nature obeyed Henry Takayama.

Fullepub

Fullepub