Chapter 14

Chapter

Fourteen

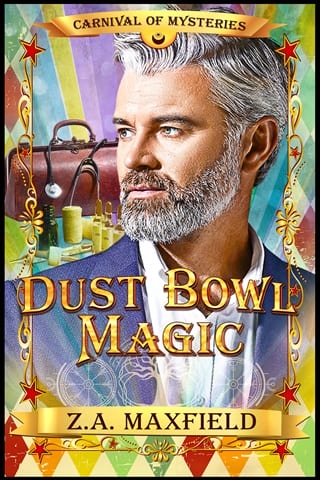

Dr. Lucas Hamilton

Something wakes me. I think it must be nearly dawn, given the hazy blue light outside the window, but the dust is blowing and it's hard to tell the time here. Someone at the clinic door knocks hard enough that the bell jingles. I've been sleeping draped over the table, drooling all over my arm. Fortunately, the cards are dry.

Jesus. "Just a minute," I call out stiffly as I get to my feet. "I'm coming."

I open the door to find a big man in coveralls and a rough work shirt. He carries a little girl in his arms. One look tells me she's febrile. Her breathing sounds labored.

"You the doctor?" His eyes are red, and even though the dust has kicked up, I think they're swollen from crying. "I didn't know what else to do."

"Come in, please." I hear Sumner moving around upstairs. I know he'll come as soon as he's dressed. "Let's take her into the examination room. Follow me."

He obeys, and as we lay the child on the table, she whimpers in pain. It's a feeble noise, strangled by her inability to get a full breath. She's protecting one side of her body, and I think I know why. Coughing is an explosive business. It's not uncommon for pneumonia patients to break ribs. I suspect this little girl has broken one or more of hers.

"Where does it hurt, sweetheart?" I try to assess the damage, but she draws her legs up to protect herself. The maneuver has to be unbearably painful, because all she can do is whine as fat tears roll down her cheeks. Her father stands beside the table and holds her hand to comfort her.

"She was like this when her ma and me woke up." He slides his arm around her protectively. "Seems like it got worse for her overnight."

As I watch, the child calms for her father.

I want to offer her something for her pain at least, but I must consult Sumner before I do anything. Frustration fills me. In the life I knew, she'd have already been seen in the ER—probably an on-call pediatrician. She'd have a pulse oximeter, blood pressure cuff, an IV with fluids, antibiotics, and pain relief. She'd be getting oxygen through a nasal canula. She'd have been to radiology, so we'd have chest x-rays to look at. By the time she reached someone like me, an anesthesiologist would be putting her out, and I'd be preparing to perform a lung transplant. I'd be this child's last line of defense, not her first, and I wouldn't have to watch helplessly—uselessly—as she and her father suffer.

I hate this quirk of fate or fever dream or whatever it is I'm experiencing right now. I hate losing. I hate this feeling of impotent rage, I hate my dependence on modern technology, but most of all, I hate myself. I've reached a place in my career where everyone believes I'm pretty hot shit, but shit's still shit.

Nausea tickles my throat.

"Hold on." I manage a reassuring voice. "Dr. Delano will be with us in a minute."

"I'm here." Sumner is still buttoning his lab coat as he enters the room. He looks calm and put together, as unflappable as always until he meets my gaze. A riot of color floods his cheeks and I'm jolted by a bolt of pure lust. I can't let it affect me. I'm trained to leave everything outside the OR, but I'll be damned if I don't revisit the sight of his prim, downcast eyes later.

"Good morning, Dr. Hamilton."

"Morning Doctor Delano. Mr.—" I look at the patient's father, whose name I didn't get.

"Morse." The man shakes Sumner's hand. "Name's Henry Morse. Folks call me Hank. This is Alice. She's four. Our youngest. All the kids have been coughing off and on, but a few nights ago, Alice took a turn for the worse. We've been worried about her, of course. Doing what we can. Last night was real bad. My wife stayed by her side all night. This morning, she tried to cry out, but she can't no more. You can see she's in pain. We didn't know what to do."

"Let me take a look." Sumner has stepped forward with his stethoscope. He's listening to her heart and lungs. Auscultation. It's been what, a hundred fifty years since the invention of the stethoscope? Sumner pulls a reflector from his pocket and says, "Open and say ah , sweetheart."

"We've been dosing her with lard and kerosene," Hank says, "on account of Evan Jacobson said it helped with his wife's cough."

I open my mouth to speak, but a look from Sumner stops me.

"I'm familiar with the practice," Sumner says. "But I'd prefer people administer fluids like water, weak broth, tea, and the like. Chamomile tea with honey helps with coughing and sore throat."

"Can you heal her?" Morse implores. "We don't have much, Doc, but what we have, we'll gladly pay if you think you can help our girl."

"I'll do everything I can, though I won't lie to you. Alice is seriously ill." He turns to me. "Could you please go over to the boarding house and see if one of the nurses can come? I'm sure Alice will feel better with a nurse to make her comfortable."

I get my clothes and shoes from the infirmary and draw the curtain to change and jam my feet into my loafers. The grit already in them makes me sorry I didn't put on socks.

"Wear a mask, Dr. Hamilton."

"Yes, Doctor Delano." I find a mask behind the intake desk and tie it on before going out into the dust-driven morning.

Wind is a malicious imp, picking up debris and hurling it with every gust. Grit grates my skin and stings my eyes as I make my way toward the boarding house. As I breathe, moisture collects in my mask. By the time I return to the clinic, the fabric will be caked with dirt and thoroughly clogged. Unlike pandemic-era Costco, here it's obvious why people prefer to go without wearing one. Prolonged use is like wearing a mud ball over your mouth and nose.

We definitely need better PPE.

I can't see ten feet in front of my face, but somehow, I reach the boarding house. Rose answers the door wearing a robe and slippers. She's the only boarder awake. The sour-sweet aroma of baking bread curls around me like cartoon scent fingers, promising something delicious. I wonder what Mrs. McKenzie is baking.

"Dr. Hamilton, I didn't expect to see you so early." Rose glances behind me, probably looking for Sumner. "Is something wrong?"

"A very sick little girl arrived just now, and Sumner asked me to see if one of you could come to the clinic early. He thinks she might be reassured by the presence of a nurse." I don't say woman, or worse yet, female, but I know that's what Sumner intends. Someone motherly.

Her expression is sympathetic. "I'll come. It'll take a few minutes for me to dress."

"I'll wait out here." I mean to lean against the wall and bear the duster as best I can, but Mrs. McKenzie appears behind Rose.

"You will do no such thing, Dr. Hamilton." She waves me inside. "I have some coffee made. Would you like a cup?"

"You're an angel." I sigh as I shake off what dust I can. "I'm afraid I didn't have time to make any at the clinic."

The fragrance of baking gets stronger the closer I move toward the kitchen.

I had a roommate in college who used to bake every Sunday. She was passionate about the practice. "Bread is the common denominator between every culture throughout history. It links the past and the future. Everywhere, in every time, people have made some kind of bread."

The truth of her words clicks for me now because this room smells just like our student apartment. Wholesome and comfortable. Welcoming.

"Something the matter, Doctor?"

"Just memories. Call me Lucas, please." I take the mug she's holding out for me. "Your kitchen smells delicious."

Her cheeks grow pink. "My boarders love it when I bake. They say it reminds them of their mothers."

"It does feel homey here." Just not my home. My mother never worked a paying job, but she hired a housekeeper and a cook the day she married my father. "I like it."

"Thank you. I'll make a basket of rolls to take with you."

"That would be very kind."

She smiles sweetly. "I know men like you and Dr. Delano. You'd forget to eat if no one reminded you. Are you married, Lucas?"

"I've never been so fortunate." I give a humble shrug along with the well-practiced line.

"Well, bread is quick and easy to grab between patients. I'll add butter and a jar of peach preserves my sister sent me from Georgia. Be sure to take care of yourself, doctor, you hear me? Otherwise, I'll be forced to storm the clinic and remind you."

"I wouldn't want you to trouble yourself to that extent." I manage to drink my coffee before Rose returns.

"I'm ready." She enters the kitchen wearing a coat over her uniform of calf-length dress and starched white apron.

"I don't know if you'll need a coat this morning."

"I want to keep tidy on the way to the clinic."

I glance at my clothes, which are brown with dust. "I didn't think of that."

"You will next time. I'll wear a mask, too." She pulls one from her pocket.

I replace mine as we head for the foyer. The wind shoves the door at me when I open it, bringing in a tide of dust. Maybe I should fashion a keffiyeh of some sort. I wish I had safety glasses.

"The entire staff should have eye protection." I shout over the wind. "We can't help anyone if we can't see."

Rose lifts her skirts away from the filthy walkway. "I'll bet someone in this town has driving goggles."

God, how I long for Amazon Prime one-day shipping. Or Instacart, which is even faster. Could I order goggles from the Sears catalogue? We'd probably have to wait for a stagecoach to deliver them. I have no money here anyway. No ID.

I'm a hot mess in this place.

The things I take for granted—technology, transportation, telecommunication, telemedicine—are a Jenga game on which I've built my life. I can't help the feeling that reality is Ponzi scheme, and all the people who lived and died before me paid the price for everything I have. Before I found myself here, anyway.

I should test the subject with Sumner, even if it makes me sound insane or unmanly. Which it will. If you've worked in a field hospital a mile or two from a trench war, you've got to be made of stern stuff. Frogs and snails and recurring nightmares. Compared to that, being blown off course—chronologically speaking—and regretting the loss of one's bank card is nothing.

Rose and I run the rest of the way to the clinic. Despite her precautions, the hem of her skirt is brown by the time we get inside. At least her coat keeps her apron tidy.

"Good man." Sumner pats my shoulder as he greets Rose. "Sorry to call on you so early, Rose. Is it very bad outside?"

"I've seen worse." She blows her nose into a linen handkerchief. "Where's our little girl?"

"In the infirmary." He lowers his voice. "She has fractured ribs. I've given her something for pain. Will you please keep her comfortable?"

Her eyes narrow with concern. "Of course, Doctor."

She's gone with a swish of skirts. Sumner indicates we should move somewhere more private, so I follow him to the dispensary.

"Things don't look good," he admits.

I know the limitations of the clinic. I need to know what we're up against. I want to help the girl, but what can we even do in a case where things aren't looking good ?

"I need to get a listen," I say. I take Sumner's stethoscope. He allows that without complaint, which—if I'm honest—surprises me. His humility is admirable.

I stop abruptly. "I'm sorry, Sumner. May I use this?"

"Go right ahead." He ushers me into the examination room with a wan smile.

Under the heavy gaze of Alice's father, I assess her color and listen to her lungs. I find diminished breath sounds in one lung, rhonchi and crackles in the other.

I briefly meet Sumner's eyes. His expression tells me what we're both thinking.

Alice's dust-weakened lungs are vulnerable to secondary infection. She likely has bacterial pneumonia. On one side, fluid is compromising her ability to get a good breath.

Thoracentesis is an option—draining fluid from the pleural space—but it's painful dangerous under these circumstances. She may not survive, even with the procedure. If she does survive, the dust she has inhaled in her young life will leave permanent scarring on her lung tissue. She'll live with limited lung capacity for the rest of her life.

Incidentally, that's as true in my time as it is in Sumner's. There is no cure for silicosis, and while treatments for pneumonia and tuberculosis and autoimmune disease—antibiotics and corticosteroids—come along fairly soon, they don't exist now.

I look on while Sumner explains the situation to the girl's father, whose grief is palpable.

"I won't sugarcoat things for kindness's sake." Sumner clears his throat. "We'll do what we can, but Alice is gravely ill."

"She seemed better only a couple days ago.…" Morse puts his head in his hands and sobs. "No, no, no, no."

I draw Sumner aside and speak in whispers.. "Surely getting Alice to one of the better hospitals in the east, away from the dust storms, will help. In a better environment with the most modern treatments available she might have a more favorable outcome."

"I don't believe Alice would survive the trip at this time," Sumner whispers.

"I can perform a thoracentesis." I'm taking a huge chance by offering this. It's usually performed with an ultrasound for pinpoint accuracy. I believe I can do it without, but the girl is already so weak. It might help her breathe more comfortably. Given time —and a miracle—she could fight this off. If we lose her I'll get tarred and feathered or whatever they do to time-traveling queer doctors who fuck up in rural America these days.

"That won't be easy on her." Sumner considers my suggestion. "I hate to put her through it."

"She has to breathe to heal." It's the only suggestion I have. Remove the fluid and ease the pressure. The lung can expand. She's more comfortable and she gets more oxygen.

"The fluid could build up again."

"If she has a bacterial infection there's every chance it will. I could put in a port and let it continue to drain, but then she'll be uncomfortable for longer and frankly, I don't think the risk/reward percentages?—"

"I know. You're right." This hurts him. This is personal. Sumner hates to lose as much as I do, but for a different reason. He treats people. He doesn't perform procedures.

I suddenly realize I want to be more like him.

I want Sumner's gravitas, his experience, his ability to carry so much light through unspeakable darkness.

I'm numb, but I hold his gaze.

He rests his hand on my shoulder. "I think you should take her home. You should do it there."

I frown. "Why?"

"Her family should be with her," he says gravely. "You'll see that they all receive what they need? Mr. Morse says the other children are sick."

"I will."

He nods. "I think you've come up with a good plan."

It's the only plan. The only help I know to give. I don't say the words, because we both desperately want to try anything that might help. We want to throw one more Hail Mary pass if that's what it takes to even up the game or at least get a first down and another chance. I'm not used to being helpless. It hurts.

Sumner interrupts my thoughts. "Do you mind helping me gather up what you'll need for the procedure?"

"Of course." He leaves the room and comes back with an old-fashioned doctor's bag. I feel sick, what if I have this wrong?

He meets my gaze. "You'll be fine, Lucas."

I've lost my arrogance. My confidence. I'm working in the dark with nothing more than aspirin and cough preparations. It's not like Médecins Sans Frontières, where conditions aren't optimal and supplies can be limited, but at least it's possible to get them.

Even the way I approach the procedure must change. I can't do the job and then hand her off to the ICU. I need to connect with her family and focus on all of their needs if I want to be half the doctor—half the man—Sumner is. I need to de-compartmentalize this procedure and be mindful these are people, not wins and losses on some imaginary scoreboard.

I have a daughter. I can't help wondering what she was like at Alice's age. I think about my parents and my colleagues, from the anesthesiologist to the janitorial staff that clean up after everyone leaves. I don't know if I'll ever get back to that life, but if I do, it will be as a changed man.

"Penny for your thoughts?" Sumner asks.

I shake my head. I'm shattering into a billion pieces.

"Let's get what we need from the dispensary." The minute we're alone, he wraps his arms around me.

We're both afraid. The difference is I'm still desperate to hide it. Sumner doesn't compartmentalize, and he's no less capable for leaving behind the need to maintain a stoic front. His eyes close as we bask in the warmth between us for as long as we dare.

"It has been a long time," Sumner whispers, "since I've sought comfort in a man's arms."

"I've never—" I shake my head, embarrassed to admit I've never looked for what we have together. I isolate—insulate—myself against the discomfort that inevitably comes with intimacy. "Not like this."

Sumner's eyes glitter. "Do you plan to disappear as enigmatically as you appeared?"

"If I have a choice, I won't keep secrets from you. I don't know what will happen." Will I be stuck in this time forever? Will I wake up in the world of Sophie's indifference and my parents' disapproval and have nothing but fading memories of my time here with him?

Sumner's eyes are clear, and bright, and stunning.

They say everything neither of us can put into words right now.

Oh my God. I love this man.

Something has changed between Sumner and me. Something that has less to do with sex and everything to do with intimacy. I want to hold this tiny growing spark in my hands, to gaze at it and feel its warmth, but I don't dare, for fear I'll smother it.

Better, I think, to let our little fire grow stronger before trying to capture and name it. It's too fragile and our lives are too tentative to count on anything.

Whatever happens, today there will be pain.

Calvin and I help bundle Alice into the ambulance, with Hank Morse in the back so he can hold her hand while Sumner drives. Calvin follows in Hank's truck. In town, neighbors turn to look as we pass. The rest of the way is desolate. We start out on paved road then turn off on some rough dirt tracks. We're driving at the speed of a funeral cortege. I don't see farmers or stock animals. Only piles of fine dirt, blowing from one side of the road to the other.

Though it looks built to last, Alice's home is little more than a main room that features a kitchen, dining, and living space with two tiny bedrooms sticking out like ears. There are three older school-age children: two boys and a girl.

Sumner and Calvin drive back in the ambulance. I tell the Morses what Sumner and I agreed we should do. I give them time to think. I make certain they know the risk.

They understand, I think, how dire the situation is. In the devastated silence, Hank shoos Alice's siblings outside. They sit on the porch while we work.

I ask June to boil water to sterilize the instruments. From canning, she probably knows more about pasteurization than I do. I clean my hands using the hottest water I can stand. We swab Alice's back with an alcoholic iodine solution because that's what we have.

Hank holds Alice while I get things ready. For the procedure, I must find the pleural cavity with a huge, museum-worthy syringe and draw out the fluid that is putting pressure on her lung. It's delicate, unlike on television when an EMT sticks a chest tube into a patient's pleural space to treat a pneumothorax. This procedure isn't as invasive as that, but it's risky here. Anything is risky here.

I numb the skin with Procaine, a cocaine derivative antecedent for Lidocaine, but Alice screams when I insert the syringe. Her parents hold her still for me, but it's scary for her. I slowly draw out the fluid and discover signs of discharge from an infection—which I was afraid of—and then it's over. We clean and bandage the small wound.

Alice's breath sounds have improved. She's breathing better on the infected side than she was before, so the procedure has done its job. If she gets better, it will be because her body fights off the infection. If not, more fluid will build up and cause the same problem and further decisions will have to be made. We make her as comfortable as we can in her shared bedroom and watch over her.

The other Morse children come in and sit quietly on the hard wood floor. Alice lies very still. Her breathing is not as restricted, but her fever is high. June bathes her skin with damp cloths. Alice sleeps fitfully. We wait and watch.

I get up just to walk around about an hour later. I need water. I get a cup and pour myself some from a pitcher on the sink. I ask if June wants one. She shakes her head.

Hank has gone outside somewhere. There are no animals and barely any crops. Maybe he's gone to pray by himself, or cry, or he keeps cigarettes or liquor in the empty barn. June doesn't remark on his absence. June gives me an enamelware mug of nettle leaf tea, and we sit together and wait.

"Sorry we only have nettle tea," she says at length. "I can give you some toasted bread."

"I'm content with the tea, thank you." I'm not going to eat what little food she has. The family is all eyes and long bones. "Dr. Delano's driving made my stomach lurch a bit."

As did terror of performing surgery at a dining room table with a prehistoric syringe.

She sips her tea. "Those roads sure can make your teeth rattle."

"Better than driving with Calvin. He likes to go fast." I realize I'm throwing a child under the bus, but I'll latch onto any conversational gambit to keep from thinking about the little girl in the next room."

"Oh, Calvin. He's a handful, that one," she says though it's obvious she's keeping her focus on the bedroom.

"He's quite the entrepreneur." I have started keeping change for when he shows up to make himself useful.

"He's got a good heart. Tends to leap in where angels won't go, if you know what I mean. We'll miss that family if they move out west."

"I understand many families are leaving." Because I've seen the documentary, I've heard it's the largest human migration in US history. Did they count indigenous people when they calculated that? I wonder.

"Farming families live on hope when they don't have nothing else." June has the colorless features common to the long-suffering farm wives I've seen here. "Some lose even that after years like we've had."

"What about you? Are you thinking of moving?"

"Nah, we won't move." She pulls her threadbare sweater closer and crosses her arms as if making herself smaller will help her bear the harsh winds outside. "Hank's a prudent man. He believes in not owing folks. This farm isn't mortgaged, and we paid cash for the equipment. Little good it does us now. We'll keep this farm going if anyone does."

"This drought can't last forever," I say automatically. Farming is the last thing on her mind.

Her eyes lift, and there's something hard in them. "Alice is going to die, isn't she."

My throat burns. "That's in God's hands."

"But you think so. That's why you brought her home." She glances toward the kitchen door. "Hank doesn't think she's gonna pull through. He'd have stayed by her side if he did. He doesn't want the other children to see him cry."

"He's only human." I wish he'd stayed, in that case. "He should let them see that."

She shakes her head. "He wants to be strong for them."

I think of Sumner, talking about his lost lover. "To my mind, it doesn't make a man weak to show his grief."

"Hank was raised to keep his feelings close." June's stiff spine seems to say she is made of the same stern stuff. "He's from proud people."

"I understand that." My father raised me to compartmentalize, after all. Circumstances have reinforced the lesson over the years. Caring fucking hurts.

"Hank comes from lush farm country back east." Her face softens. "He's never known trouble he can't fix by working harder. Men like him are questioning everything they thought they knew."

"Not you?" I ask because the tilt of her chin seems to dare me.

"Women are allowed quiet disappointments and domestic failures. It's not the same." She rises from her chair with some effort. "I'll go be with Alice now."

"I'll be here if you need me." I watch her join the vigil with her children.

The shadows lengthen, and the sun goes down. A couple of times, June calls for me. Alice doesn't wake, but her breathing changes from time to time. It grows more labored as the night wears on. Listening to her chest, it's clear she's not getting better.

Hank slinks in after nine by the clock on the mantle. He smells of tobacco, but not alcohol. He's been crying.

"Is—" His voice cracks. "Is there anything I can do?"

"Be with your wife and children. They need their dad."

He swallows hard, but he eases himself into the small room where his family is rapidly losing hope. The oldest boy rides herd on his siblings until one by one, they fall asleep. Lantern light throws monstrous shadows onto the walls.

Just before dawn, Alice grows restless. She opens her eyes wide and rasps the words, "Why is everyone staring at me?"

She tells her mother she wants Johnny cakes.

The family greets her sudden declaration with joy, but she's lost her battle. Her breathing pauses more and she stays still longer between breaths. She opens her eyes and asks again, "Why are you staring?" She calls for her mother to hold her, to cover her. She says she's cold, though she's bundled in every blanket they own.

June shoos the older children out. I go with them. They sit on the porch in a stunned sort of silence that breaks my heart. I selfishly wish I'd stayed in the clinic, where I know a look from Sumner would shore me up for the grief to come. It hasn't been a week and already Sumner is my rock. He's on my mind, in my heart, as necessary as the air I breathe.

Hank and June remain with Alice until the end. They stay with her in quiet grief after she passes. They've done this before because death isn't sterile in rural America at this time. Not yet. Death here isn't something that happens in hospitals and gets passed off to morticians. It's not a passive act. It's something that happens to families, not individuals, and families take care of it.

This is a living history lesson whether I like it or not.

The other Morse children are hungry, but no one complains. June emerges from the sickroom, and they cling to her, siphoning the strength that good farm women like June have in infinite supply.

This. This resilience is what keeps a farmer going. The dogged determination to wait for the next rain, the next crop, the next year. It's the assumption the next thing will be better because it must be. This belief is so ruthlessly human I can't bear it.

Hank takes the children outside again.

June cleans Alice's body on the kitchen table, cuts a few locks of her hair, and dresses her in her best dress. She uses a cloth bandage to tie Alice's jaws together before Hank and I arrange her securely on a board for travel. I stay professional as I'm introduced to death as I've never, not once, seen it before.

June lights the stove on a new day. Her family still needs to eat.

"I'm sorry for your loss," I tell her as shame bleeds from every one of my pores.

She nods, then turns away to gather he children to her.

Hank and I drive Alice to the mortuary. Hank is at the wheel of his truck with Alice's board stretched across the seat beside him. I ride in the truck bed, pretending my eyes are damp and red from the inevitable clouds of dust in the air.

Once we arrive, I get directions and walk the short distance from the mortuary to the clinic.

Sumner greets me warmly.

"Bad night?" He holds a mug of hot coffee out for me.

I take the cup and sip deeply. The coffee is bitter and hot enough to scald, but I barely taste it or feel its burn.

I have nothing to say, though I sense Sumner expects a greeting, at least. I can't give him even that.

"You should know that Calvin and Pastor Andersen will be moving our infirmary patients to the Red Cross hospital in Beaver County this afternoon," Sumner says. "Everyone else we've seen today has gone home."

I follow Sumner into the infirmary. We're still as statues for a long time, watching an older couple there sleep restlessly. There are things I ought to be doing, but I can't seem to make my body move.

The fight to live up to others' expectation has kept me moving like a clockwork man for over two decades. I never imagined the fate of one little girl could break me.

"C'mon, you." Sumner places his hand at the small of my back. Warmth spreads to the tips of my fingers and toes. "You'll fall down if you don't get some sleep."

He guides me up the stairs where I fall into Sumner's bed unmindful of my dusty clothes and the people downstairs. I've never fallen apart like this, but apparently I've finally learned how, because I admire Sumner, because I'm not alone.

Sumner gently removes my shoes. He lets his fingers linger on my ankle, holding that single part of me, pushing his kindness into my bones. He covers me with a blanket. I wish I could be happier about these things, but the nagging feeling that this is all an illusion or worse, a delusion, holds me back. Even if what's growing between us is real, it can never last.

I catch his hand and meet his gaze and say nothing. Sumner smiles, and I melt into a schoolboy sort of dizzy happiness. To me, he's the original flame Prometheus carried from Olympus.

I don't tell him that. We all hide the most vulnerable thing about ourselves.

Fullepub

Fullepub