Chapter 5

5

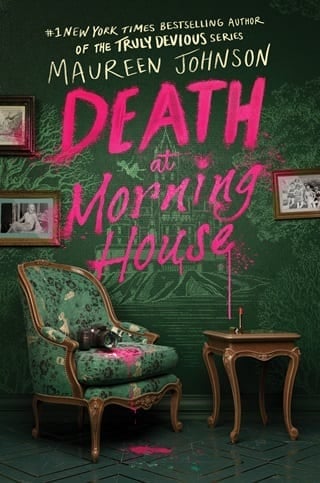

My first impression of Dr. Belinda Henson was that she looked like a praying mantis—green, long, and strangely arranged, with big bug eyes. She was sitting on a chair on the veranda dressed in expensive athleisure—yoga leggings and a snug top in a bright, verdant jade. Her limbs were tangled together in a complicated position that looked uncomfortable to me. She had a face shaped like an upside-down raindrop—a wide forehead tapering rapidly down to a pointed chin. Her hair was a quiff of white gray, and she wore large sunglasses to hold back the late afternoon sun. Her attention was on the viewing screen of a camera she was holding. It was a serious piece of equipment, with a long telephoto lens. April and I stood there for a long moment until she finally tipped her head up in our direction.

"Marlowe," she said. "Marlowe Wexler."

I held up my hand in a sheepish hello gesture.

She uncoiled herself and stood. She took me in with a dispassionate gaze, and the resulting look on her face suggested that while she wanted more from the situation, she knew better than to expect it.

"I'm Belinda Henson," she said. "And you're the one who burned down someone's house."

"Well," I replied. "Not all the way."

I am not only truthful—I am modest.

"I'm told you have a good memory."

I was probably supposed to say yes, yes I did. To nod. To show that in some way bringing me here was worthwhile. But I just stood there because I have no capacity to take a compliment. She waited for my reply for a moment, then shook her head gently. I looked to April, but she had tiptoed off into the shadows.

"Have you read the manual?" Dr. Henson asked.

I said that I had.

"Do you remember what year the house was built?"

"Between 1920 and 1922."

"Cost?"

"Four million."

"What kind of a diet did the family follow?"

"Natural foods," I said. "Following the prescription of Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, the family refrained from consuming meat, refined wheat, alcohol, caffeine, or sugar. A typical breakfast consisted of plain yogurt, stewed fruit, juice, boiled milk, nut cutlets, mushy peas, and prune toast."

"Verbatim from the guide," she said approvingly. "Good. People love those details about the mushy peas and prune toast because it's disgusting. Ralston was obsessed with health, which is funny, because his family came from tobacco. His family was very much a part of the Gilded Age scene in New York City, not the richest of the rich, but close enough."

She quizzed me for another few minutes, asking me about the members of the family, what kind of stone had been used for the house, who the architects were. I started to ease into the questions. I like a quiz—and it's easier to show people I can remember things rather than just say I can.

"All right," she said, nodding approvingly. "It seems Wren Gibson was right about your memory."

So Mx. Gibson's first name was Wren. It always catches me off guard when I find out that teachers have things like first names and friends. I know this logically. They're people. But it's always disorienting to find these things out and realize there's so much we don't know about the people we see every day.

Dr. Henson opened the massive front door. It looked like a door that should creak as you pushed it, and that bats should fly out, but it had a silent, well-crafted glide. My first impression of Morning House was that everything twinkled. The sun seemed to be everywhere, jumping from mirrors, refracting from crystal doorknobs. This huge room was made of wood—wood-paneled walls, wooden floor—but it all glowed.

"That's part of the design," she said, following my gaze. "The way the light comes into the house and bounces around. Phillip Ralston was a man who liked to control his environment, I think it's fair to say. Look up."

I tipped my head back and saw a domed ceiling made of stained glass. The center was a kind of sunburst—orange and yellow and brown and white—radiating and changing into blue and lavender. But every piece was a different shape. There were sunbeams and tendrils and waving lines, all of which ended in a ring of human faces, I think women, with golden hair. They were at the outer rim of the wild mosaic, looking down.

"It's a masterpiece," Dr. Henson said. "Made of over twenty thousand pieces of glass. It's incredible that it's lasted all these years and that it's in such good condition. The same could be said of this whole place. I'm sure you've heard, this is the first and only summer this house has been open to the public. It's been sitting disused since 1932. There was a local effort to try to buy it and preserve it, open it up for tours, but the town couldn't raise the money. As a gesture to the community, the group that bought it is letting the town run tours here for one summer."

Dr. Henson proceeded to give me a walk-through, not quite a tour, the names of the rooms tossed off as we walked past doors. The first floor of Morning House was composed of rooms for every time of day. There was a breakfast room with long windows; a sitting room for the afternoons with views over a garden; and a library with a massive fireplace for cool evenings.

Through a set of bottle-green double doors, there was a grand dining room. It was an impressive space, self-assured as a church, with a green marble floor cut through in geometric patterns in black and gold. The table looked like it could seat a hundred, so just the tail end had been covered in white and silver plastic tablecloths. Mahogany wainscotting hugged the room from below, while the top section of the walls was papered in a moss green, run through with fine lines of green and gold. It was too fresh and clean to have been original.

"When the family left the house, the furniture was put into storage. Some was used later or sold, but luckily for us, a lot of it remained. We got it out a few months ago, cleaned it up, and restored it to its original position, as far as we could determine. I'm not someone who usually does this kind of thing. I'm here because I'm working on a book about the family. I'm in charge in the sense that someone has to be, and being here helps me do my work."

We walked toward the back of the house, where there was a large room full of ancient gym equipment—gymnastic horses and rings, a wooden rowing machine, an old leather punching bag.

"The exercise room," she said. "A major part of the family's life. They had strange views about health."

She opened a door at the back of the gym, revealing a white-and-green-tiled room that might have been a bathroom, or maybe a lab. It had some health-adjacent purpose. It had things like a massage table and a large shower with lots of heads. There was a steam box with a stool in it and a space where your head would come out the top. I could sort of guess what that was for. I couldn't say the same about the object at the far end of the room, a kind of elaborate casket that was filled with lightbulbs.

"What was this for?"

"Some quackery," she replied. "It's a sunbed, but it seems designed to electrocute you. Nothing in this room seems safe. They were obsessed with digestion, so maybe something to do with that. Take this, for instance."

She nodded toward a boxy wooden chair with a hole in the seat. It wasn't quite a toilet, but I could see it was in the toilet family—a truly upsetting relative with a threatening aura.

"One strange thing about this house," she continued as we walked back into the main hall and started up the grand stairs that led up to a series of other floors, all edged in balconies that opened onto the space. "In most of the places along here on the river—the big houses—the whole point was that they were set up for visitors. You came here for the summer and you brought friends. Morning House had no dedicated guest rooms. This family needed a lot of bedrooms. Can you name the members of the Ralston family?"

"Dr. Phillip Ralston," I said. "He was the dad. He was married to Faye. He adopted six kids—Clara, William, Victory, Unity, Edward, and Benjamin. He had a younger son named Max."

"Good. They all had bedrooms here on the second floor. Phillip, Faye, and Max and his nanny over on the left, and the six older children this way..."

She pointed toward a hall with six identical white doors with ornate brass handles but did not stop her progress. She indicated a doorway on a landing halfway up the steps to the third floor.

"It's a half level," she said. "In the time Morning House was built, the higher up in the house you slept, the lower your status."

"That makes no sense," I said. "Aren't the views better from the top?"

"Don't mistake wealth for logic. The servants' rooms began on the third floor, though they also slept on the fourth and in the turret. They put in this halfway room for Dagmar, Phillip's sister. When the house was originally built, she had Max's room. But when Max came, they had to switch things around. Max was a baby and needed to be near his mother. It wouldn't be proper for Dagmar to be on the same level as the servants, so they built out a little and made this room, the second-and-a-half floor. It's a very nice room. It's my room, in fact, so it's not part of the tour."

She kept going to the top floor. We were almost level with the glass dome, and I could see the eyes of the glass women up close—luminous and blue, still clear as ice after a hundred years. Here, the walls were not papered or paneled in fine wood. They were simple white plaster with the occasional pane of clear plexiglass covering up some raw wood planking. While the space was empty, the walls were not. There was writing all over them, and some carvings as well. Names. Dates. Initials. In some cases, they had carved their initials into the plaster so deeply that I could get my finger into the grooves up to the first knuckle.

"This is also part of Morning House," Belinda said. "The people took it over long after the Ralstons left. When I was a kid, growing up here, we used to come to the island all the time. It was where we had parties and explored. Everything you can imagine, that's what we used this abandoned mansion for. People did that for years."

Clearly. The graffiti artists often dated their work. The dates ranged from 1944 up until around five years ago.

"You grew up near here?"

"Oh yes. I'm a local. Morning House has always been on my horizon. We all knew the stories. In fact..."

She scanned down the wall near the doorway until she spotted a small message in black ink.

"Here I am," she said.

I looked and saw a message: BELINDA HENSON WUZ HERE, WITH HER BEER, JUNE 4, 1977.

"Probably not the smartest thing to sign your destruction of private property, but we all did it. The general impression was if you only defaced the fourth floor it would be okay, and it was. As long as you didn't do it in this last room, which was Faye's favorite."

I followed through a set of tall French doors. This room had a vaulted ceiling and traces of silver wallpaper with trailing pink roses.

"She would sing up here," she said. "The sound would fill the house. There are cabinets built into the walls of this room. They used to store chairs so they could hold recitals here. In theory, anyway. No one ever came to visit, so there were no recitals, and now, no chairs."

She indicated a panel in the wall and gave it a gentle press, revealing a closet with a vacuum and some buckets, along with a yoga mat.

"I do yoga up here every morning at sunrise," she said. "I keep my mat here. But there's also something very important that you'll find in this closet and in all the rooms."

She pointed to a red box marked WINDOW FIRE LADDER. I got the message.

"I am not a babysitter."

I hadn't just asked, "Hey, Dr. Henson, are you a babysitter? Is that how you would describe yourself?" But she spoke like I had, and she was kind of mad about it.

"I care more about the family than the furnishings, but you can learn a lot about people from their homes, obviously. Morning House is Philip Ralston's creation, and it contains some glimpses into his mind. Come this way. I won't be breathing down your neck. As long as you all do your jobs safely, I don't care what you get up to. But no candles. The idiots..."

She seemed to want to correct herself, then shrugged.

"... who bought this place are setting the fireplaces back up and I saw candles down there in their supplies, but do not use them. The fire ladders are in all the upstairs rooms. I'll have April show you. Van will forget. He's good with the presentation, less on some of the details. A child almost climbed up a chimney the other day. Do not let children climb the chimneys."

"No children in chimneys," I repeated.

She opened the doors that led out onto a massive balcony that was the roof of the floor below. It was trimmed in a crenellated wall, all unfurnished. From here, the water looked less glassy and green and more like a rippling muscle of steel blue. There were two islands right in front of us, one with a high cliff edge, and a smaller one with a single green house. More were in the distance, small and insignificant.

"This is the highest point on this section of the river," Dr. Henson said, walking to the edge. "You can see for miles. I take a lot of photos from here. I've gotten some amazing pictures of birds. There's a pair of bald eagles that sometimes perch on the oak on the far right. That's the best thing to see. The worst is what people get up to..."

She had a haunted air as she said this, and I had immediate visions of naked grandparent parties on boats with names like I'm Knot That Drunk . I may have been scarred by my own experiences in Key West. My grandparents' best friends are their hippie neighbors, and I accidentally got a look at someone's entire ass through the screen door as they bent over to get the remote. Sometimes, right before I fall asleep, it appears in my mind. The floating ass, wasting away in Margaritaville.

"This is the most popular thing visitors come to see on this island," she said. I immediately started scanning the view, but she shook her head.

"Look down."

I looked over the side of the balcony, to the ground four stories down. Directly below us, in between the bit of garden and the other balconies and porches, was rubble and nothing else.

"Where is it?" I asked. "What is it?"

"You're looking at it. That's the death spot. You see, the story of the Ralstons is lore around here. It's what made this place so alluring, so mysterious."

I'd read the basics of this in the manual. It was a sad story. On the twenty-seventh of July, 1932, Max Ralston—who was four years old—slipped out of the house without anyone noticing. When they did, there was a massive search. It was his oldest sister, Clara, who found his body at the bottom of the lagoon. The family was in shock. Clara went off by herself for the rest of the day. She returned to the house that evening, seemingly intoxicated and wild with sadness, and fell from what must have been this balcony.

"The witnesses said she seemed to be dancing before she threw herself off," Dr. Henson said, adjusting her huge glasses. "She landed on the patio below, where the rubble is.

The family immediately left the island—within a few days—and they never came back. The only thing Phillip did to the house after he left was to have the patio where Clara landed smashed to pieces. People always want to see it, but they're disappointed that it doesn't make for a good picture. Anyway..."

Clara's death spot was summarily dismissed.

"... you'll be getting the details a lot over the next few days. If you've learned what's in the manual, you should have no problem. I'm sure the others will help you."

She said this in a tone that suggested that the others may or may not help me and that she didn't care much either way.

"It's good to have someone from outside of town to keep an eye on things. And if anything is off, you'll come and tell me."

"Off?"

"Not off, but..." She stopped herself and cocked her head slightly, as if puzzled by her own remark. "... if you have concerns. As I said, I'm not the babysitter, but I want to make sure everyone's getting along."

I had no idea what any of that was about, except that it sounded like I was supposed to narc on the others if they did something wrong. Dr. Henson looked out at the view and the other islands in a dispassionate way, signaling that she had no more to say about the subject. She had made it clear: she didn't care about our creepy teenage problems. Not in a mean way. Just in a not-caring way. Frankly, that's how I like my authority figures.

"You must be glad they saved it," I said. "All this history."

I said this as an offhand remark—something you do to punctuate a conversation. Like nice to meet you or have a good day or this concludes my TED Talk . I wasn't thinking much of anything aside from that the view was nice, I missed Akilah, and I wondered how many nights in a row I could just eat hot dogs until everyone else here dismissed me as a dirtbag. So I was confused when Dr. Henson said, "No, not really."

"No?"

"No. That's not how history works. We don't save every monument just because it's big or because it's there. Lots of things are big, lots of things are there . Some things should be allowed to fall down. But this is still here, so we do the best with it that we can. Anyway, why don't you take the opportunity to look around. You'll start training tomorrow."

With that, she left me alone with the view of the river and my little weird thoughts.

Fullepub

Fullepub