Interlude

INTERLUDE

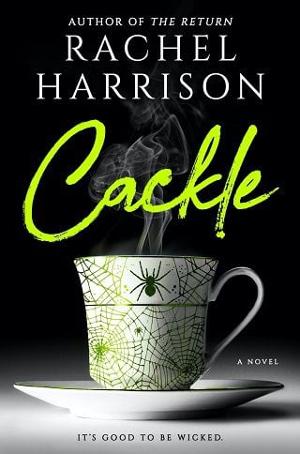

In the weeks after the date, Jill, along with the rest of the staff, avoids me like I’m a leper on fire. I assume Jill told them what happened and I have to admit that between the Chris Bersten spider incident and the bone-date incident, they’re fully justified in being wary of me, though, since the date, there have been no other suspicious occurrences on my end.

It’s unclear if it’s a phenomenon I can control. My curiosity has been outwrestled by my extreme apprehension. I try not to give it too much thought. I’m well aware I can’t avoid it forever, but that’s a problem for future me.

Present me has melded herself to her routine. It’s a source of stability, instilling a much-needed sense of normalcy in my life. There’s comfort in the simplicity of doing the same thing every day, every week. There’s beauty in the ritual.

I get up, stop for coffee at the Good Mug, go to work, pretend the whole school doesn’t suspect I’ve got evil powers—which is TBD, I guess—come home, take a shower, eat an easy dinner like a frozen burrito or scrambled eggs or peanut butter on bread, drink a glass or bottle of wine or occasionally something stronger, watch a TV show and, depending on any romantic story lines in the show, maybe fit in a quick ugly cry or go straight to bed. Most weeknights I’m asleep by nine p.m. at the latest.

The weekends, though . . . The weekends I spend with Sophie. On the weekends, I’m not lonely at all. I’m eating homemade strudel, dressed head to toe in silk and soft velvet. I’m lounging around the library reading old books, or in the conservatory tending to flowers. I’m playing shuffleboard or dancing or watching an old movie where the actors are all hams. There have been no ghost sightings since Sophie captured all the ghosts and put them in the basement.

It’s been blissful.

But fleeting.

I’m too ashamed to admit to Sophie that I can’t maintain my happiness on my own. That when she’s not around, I’m a pathetic mess who eats meals off of paper towels and uses her sleeves as tissues. She gets impatient at any mention of Sam or if I make any implication that I’m unsatisfied in my singledom. So I try to keep this aspect of my life, of my routine, to myself.

But. Sophie’s not stupid. When she suspects I’m having a particularly rough time, she’ll send me home with Ralph. She’s done it on multiple occasions.

“Why don’t you take Ralph this week, pet?” she’ll say, and Ralph will crawl out of her pocket and into her hand, then make his way into my hand. He’ll look up at me, smiling his big silly smile, and we’ll walk home together.

I made him a tiny bed out of a cereal box. It’s got a tall headboard and a sponge for a mattress. I covered the headboard in orange construction paper because orange is his favorite color. I covered the sponge with an old pillowcase.

He loves it.

He also loves to watch TV with me. I’ll let him use the remote, pick whatever he wants. He particularly enjoys HGTV and home-makeover shows. Also cooking competitions.

“You’re so silly, Ralph,” I’ll say, and he’ll smile, march his little legs.

It’s astonishing how normal it is to love a creature you’re not supposed to love.

It’s astonishing what you’ll accept when you want love. When you need it. You’ll welcome it in any form, from anyone, anything, regardless of circumstance, however peculiar. However fantastical.

I wonder all the time if I’m desperate, and I definitely am, but the truth is, anyone would be happy to love Ralph. And be loved by him. He really is great company. The most adorable spider.

And he does help. If I cry, he cries. His cries are terrible. He makes this horrible, high-pitched squeaking noise. It’s enough to discourage me. Also, he’s too cute. After one look at him, it’s hard to be sad about anything. Even Sam. And dying alone.

Ralph does not like Sam. If I pull up pictures of Sam or open my phone to text Sam, Ralph goes crazy. He’ll run up the walls. Stomp his legs. Turn the volume all the way up on the TV. He’ll demand my attention. Usually, he distracts me for long enough that I give up on Sam.

At night, I put his bed on my nightstand and he climbs on. I pull a fuzzy washcloth over him as a blanket. He vibrates with glee. He likes to be cozy.

I don’t blame him. December has been ruthless. It’s already snowed three times. Two delayed school openings and one magical Sunday at Sophie’s watching flurries fall through the big windows in the ballroom while drinking hot chocolate with chunky marshmallows.

My dad doesn’t call to ask if I’ll be coming back to Connecticut to celebrate Christmas with him. He doesn’t text. He does send an e-mail with the entire content of that e-mail in the subject line.

I respond quickly, telling him no, I won’t be able to make it, though I don’t have any alternate plans and the idea of spending the holidays alone is daunting. Sam was big on Christmas. We’d spend it with his family in Maryland, dress up in matching pajamas and eat strictly carbohydrates, watch all the stop-motion specials. He’d often declare that it was his favorite holiday, which I’ve since come to suspect was a tactic to deflate the significance of all other holidays, specifically my two favorites: Valentine’s Day, for obvious reasons, and New Year’s, which Sam found particularly baffling.

“It’s a clean slate,” I’d tell him.

“It’s another day,” he’d say. “It’s just another day in a series of days.”

“I like resolutions. It’s hopeful!”

“You can make resolutions literally any day.”

I would pout and eventually give up on whatever grand ideas I had for an intimate, lavish, champagne-soaked NYE dinner, a spin class and a couples massage on New Year’s Day. Mason jars filled with resolutions.

It’s bad enough I have to suffer through the carols and commercials reminding me of my ex-boyfriend’s favorite time of year. The thought of having no one to kiss at midnight is a devastation I hadn’t accounted for in my log of sad, unfortunate single-person stuff.

When I lament to Sophie about the holidays, she makes a sour face.

“I don’t approve of the sentiment,” she says, shuddering, “but I do enjoy the decorations. Some of them, anyway. The trees are my favorite. Beautiful.”

“Yeah.” I sigh.

“You should celebrate the winter solstice with me,” she says. “I’ll throw us a marvelous party.”

“That sounds nice.”

“What is it, pet? You still look down.”

“I’ve always liked New Year’s. Staying up until midnight. Making resolutions. But it’s pretty pathetic if you’re single.”

She balks. “Please, Annie Crane, never say anything like that again. We’re celebrating.”

We decide Sophie will host me for the winter solstice, and I’ll host her for New Year’s Eve.

In preparation, I buy garland and string lights and sparkly silver pinecones. I buy two bottles of champagne. I have to go back out to buy a stepladder and thumbtacks to adhere the lights to the walls. I go out a third time to get replacement champagne, since I drink one of the bottles to ease the stress and agitation of hanging the lights.

But of course, Sophie puts me to shame. When I arrive at her house for the winter solstice, she opens the door for me in an extravagant purple gown. It has intricate beading and embroidery, a corset back and a long train. Her hair is in a braided updo laced with flowers. A whole flower arrangement, actually. The way she has it, it’s like the flowers are growing out of her head.

There are more flowers. Everywhere, on every surface. Massive arrangements. There are candles. There’s a roasted chicken, and sweet potatoes and carrots and an apple slaw. For dessert, she made a fruitcake with a maple glaze. There’s blackberry wine.

“Only for special occasions,” she tells me as she pours me a generous glass.

After dinner, around nine o’clock, Sophie brings me upstairs to give me a present. It’s a dress, nearly identical to hers, except mine is a warm pink.

“Thank you! Thank you!” I say, as I go into her closet to put it on. When I reemerge in the dress, I do a spin, and Sophie throws a hand over her brow from the drama of it all.

“Gorgeous,” she says. “My Annie.”

She made Ralph an outfit as well. He wears a small navy bow tie and top hat.

“You look very handsome,” I tell him.

He beams.

We go down to the ballroom and drink another bottle of blackberry wine and dance by candlelight. I don’t know if it’s the wine or the intimacy of wearing matching dresses, but something possesses me with the courage to ask.

“Can I ask you something?” I shout over the music. We’re listening to Britney again, Sophie’s favorite.

“Yes, darling,” she says.

“How does it work?”

“How does what work, pet?”

“The . . . the . . . I don’t know! Like, how did I project graffiti onto the bathroom stall? How did I do that thing with the bones? It wasn’t intentional. It just happened.”

“Strange, isn’t it?” she says. “How things just happen.”

She grabs my hands and spins me around and around.

“Sophie.”

We stop spinning. She cradles my face in her palms. “You have to surrender, Annie.”

“To what?”

“No, no,” she says, laughing. “You must surrender everything for everything.”

She twirls away from me.

I realize she isn’t going to elaborate.

So I surrender to the night. I surrender to dancing wildly and to blackberry wine. I pour a drop out for Ralph. He drinks it, hiccups, stumbles a few steps, then passes out on his back.

Just shy of midnight, Sophie leads me out to the backyard. There’s a bonfire. I’m drunk, and through my eyes, the world is opaque, the sky velvety, lush, constellations like strings of pearls. I watch Sophie lay wreaths of winter jasmine. She circles around the fire like the obedient hands of a clock. She’s barefoot.

There’s this moment when, through the fine ribbons of smoke and curtains of yellow flames, I think I see her, though I also feel her next to me, braiding flowers into my hair.

“There’s someone else,” I tell her. “Who is it?”

She isn’t there to answer. Only her shadow. Beside me. Somehow independent of her. Untethered, tucking a pansy behind my ear.

—I wake up the next morning with a dry mouth and a hangover.

“Dear, dear,” Sophie says, looking particularly radiant over a breakfast of eggs and fresh biscuits. She can’t have slept much, so I don’t know how she looks so well rested. She made me a face cream with rose hip and orange peel. She said it was the one she used, and it made my skin soft, but sadly, it did not make me ethereally beautiful.

She brews me an herbal tea that I’m hesitant to drink, considering the last time she gave me a home blend I hallucinated. She insists it will alleviate my hangover. I relent, and she’s right. I do feel better.

“What are your plans for the week?” she asks me.

I sigh. “To be either drunk or asleep, ideally.”

“Why don’t you stay here? Stay the week. I can give you clothes. You have a toothbrush. What more could you need?”

“Nothing,” I say. “Nothing at all.”

So I stay with Sophie. I stay with her through New Year’s, the decorations and champagne back at my place pointless.

I don’t mind. I’m happy to be with Sophie. Happy to be occupied.

And most of all, happy not to be alone.

Like Sam, Sophie doesn’t understand my enthusiasm for New Year’s.

“I’ve been alive for so many years,” she says. “I think it’s made me a bit indifferent. Besides, I honor the passing of time on the solstice.”

“Oh,” I say.

“But you enjoy New Year’s, so we shall celebrate!”

“We don’t have to.”

“We don’t have to do anything, darling. We’re free,” she says. “And freedom means doing what you want. I think I’ll make duck.”

She makes us duck and brussels sprouts. She makes us flower crowns. She has us write resolutions on pieces of parchment with quill pens, fold them and burn them over a special candle she made and placed inside a pewter bowl. The candle smells like sage. When we burn the parchment, the flame turns purple.

“Is that good?” I ask her.

She doesn’t answer.

I have a lot of lofty resolutions, like being more patient, like not forgetting to put on deodorant, like learning to make things the way that Sophie makes things—food and soaps and tonics and balms.

Like overcoming my uncertainty and figuring out how to wield whatever power I had that night at Rhineland.

Like finally getting over Sam.

As midnight approaches and we sit watching the grandfather clock in the library, I confess to her my sadness about not having anyone to kiss at midnight.

“Is that your measure of joy?” she asks, deadpan. “Kissing a man?”

“I guess not,” I say. “When you put it like that . . .”

“You have to let it go, Annie,” she says. “Promise me. At the stroke of midnight. No more of this self-pitying talk about being single or alone or missing Sam. He gave you a gift. Look at where you are now. This is only the beginning.”

“You’re right,” I say. “I’ll try. I can promise you I’ll try.”

“Good,” she says. “I’m very serious about promises.”

“I know.”

“Very, very serious.”

“I know, Sophie. I promise you, I will try.”

She smiles and moves herself closer to me on the couch, resting her head on my shoulder. Ralph has fallen asleep on my knee, his legs spread out flat, his top hat askew.

When the clock strikes midnight, the lights flicker, and I have a strange, evanescent vision. I see a version of myself I don’t quite recognize parting the dark, standing before me and wearing an alien grin.

I rub my eyes and blame the wine.

“Happy New Year, pet,” Sophie says, raising a glass to me. “May it be your best one yet.”

“Happy New Year, Sophie.”

When I leave a few days later to go back to my apartment and my routine, Sophie sends Ralph with me.

“Why doesn’t he live with you for a little while?” she says. “Keep him.”

I don’t do much of anything the first week of January, but I do teach Ralph how to play fetch.

Fullepub

Fullepub