Letter

Siena—

One day, you will find this. I pray you will. And as you know, I am not a praying man.

You will never understand just how sorry I am for concealing the truth from you. I'm even sorrier for the pain you are about to endure. But it is essential pain. If you do not bear it, the layers between our world and the Briardark will thin to the point of no return.

Let's stop this from happening, you and I. We'll start with the truths, and then the secrets.

I really did fall in love with Deadswitch for its landscape. There is something so special about the Sierras. The range feels like a barrier of sorts, as if by hiking through it, you are passing from one realm to another.

Did you know that between the Mojave and Mammoth, there is no road that will take you from the western side of the range to the eastern side? The mountains are too dramatic for such a passage.

What am I saying—of course you know. You know this range as well as I do. Except for Deadswitch. I told you to wait for Deadswitch until you could enjoy it. I'm honestly surprised you listened. You were always one to challenge me.

And now for the secrets.

I may have been surprised that you listened, but I was also relieved. I didn't want you to wait to enter Deadswitch just for the sake of enjoying it when you were finally well versed in your field. I did it for your temporary safety, which I'm sure you are understanding by this point.

I wish it didn't have to come to this. The tragic thing is that it had to. I lied to you about having not returned to this cabin since '97. I have returned many times, on my own, but not for Deadswitch. For another place.

When we started our studies, our goal was to monitor the glacier. Things changed once we were up here. We began noticing anomalies, not just in the glacier itself, but in the biological composition of the entire mountain. Trees seemed to shift from their place in the earth, their cells unlike anything we'd ever seen before. None of us were biologists, but we all knew the stark difference between animal cells and xylem. We began noticing the appearance of flora and growth alien to the mountain's habitat, growth that appeared one day and vanished the next. Some days, the sky began to glow the strangest shades of green before returning to normal, like some kind of quiet electrical storm.

At this point, I should have focused my attention on why we had hiked up: Alpenglow. A glacier melting far too quickly, a sign of the climate's brink. Studying the other anomalies was a project reserved for a much larger team with ample funding. There wasn't much we could do with our equipment.

But I made a choice, a choice that, over a period of five years, would destroy the lives of my fellow researchers and inevitably disband us. It would reveal the end of our world.

I chose the mystery. The unknown, something that was no longer a string board of anomalies, but far more awesome and insidious than I could have ever imagined.

I documented our findings for my successor. For you. And I'm glad I did, because I'm certain this secret will outlive me.

I'm dying. I almost died getting up this mountain for the last time. The cancer came on quick; a part of me wonders if the sickness is even from this world. But that doesn't matter. The only thing that matters is what comes next.

First, you need to read through the research we performed. I know it may seem like a lot, but you must understand the finite details in order to successfully pick up where I left off.

You'll also find an annotated map in one of the boxes. Take it. Learn it. Memorize it. Look at it so much that you see it on the back of your eyelids before you fall asleep. This is very important. You will lose items quickly in the Briardark, but you can't lose what is a part of you.

You'll understand what you must do. I've run out of time. So much depends on you.

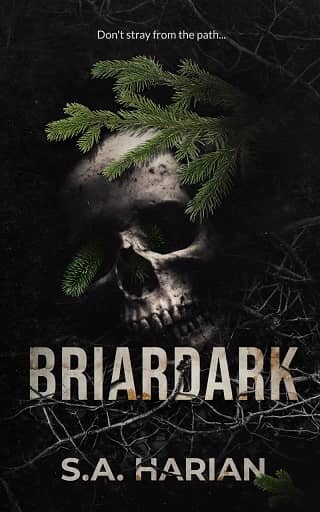

Find The Mother, Siena. And whatever you do, don't stray from the path.

—Wilder Feyrer

Fullepub

Fullepub