Chapter 2

Two

“… and so, you see, kind sir, this is why I cannot accept your invitation to drive in Hyde Park with you this Saturday, as flattered as I am by the offer .”

Lawrence sighed and refolded the letter he’d received from Lady Harriet Longstead several days before, tucking it into his traveling bag, along with the mountain of other communication he’d received since arriving in London.

“You can have this taken down to the carriage now, Danforth,” he said as Godwin House’s butler stepped into the room, two of the footmen behind him. He closed the case, but left it to Danforth and the others to secure as he headed out of the room. “I’m ready to leave all this behind me and return to the wilds from whence I came.”

He spoke with a smile and clapped Danforth on the arm before stepping away, but his heart was heavier than he wanted it to be. Lady Harriet’s letter was one of at least a dozen similarly gentle rejections he’d received in the last month. It was bad enough that it had taken him more than a quarter of an hour to puzzle out each letter when they were received, and it was not as if he cared overly much for any of the young ladies who had turned down his potential offers of courtship, but the rejection stung all the same.

His father had ordered that Lawrence and all his brothers and cousins marry, and he had proclaimed that the last of them to do so would inherit the cursed Godwin Castle. That had been in the spring, and now the year was waning. Cedric, Alden, and Waldorf had all found themselves the loveliest of brides. They were all exceedingly lucky in their choices as well. It was more than just being free of the burden of Godwin Castle, they were all blissfully happy.

The only two of them left unmarried were Lawrence and his cousin, Dunstan. And while some might argue that Dunstan was a lost cause, after being so cruelly eviscerated by his deceased wife in the few, short years of their marriage, Lawrence had his own theories about how Dunstan might surprise everyone by making it to the altar, sooner rather than later.

That left Lawrence as the presumptive heir to the family curse, and truly, there were days when he felt as though it had already fallen upon him.

He was trying to find himself a bride, trying desperately. It was not as though he did not want to marry and have a family, although at his age, approaching fifty, he was not certain he had the constitution for raising a gaggle of children. He yearned for marriage, longed to find a woman with whom he could spend what he liked to think was the second half of his life.

But Lawrence had never been lucky in love. He had a string of failed affairs behind him with nothing more to show for it than a gallery of erotic sculptures inspired by mistresses of the past and sketches of past fancies who had never taken him seriously. Possibly because of said gallery of erotic sculptures.

The fact of the matter was that as Lawrence’s reputation as a sculptor grew, his seriousness as a marriage prospect for the young ladies of the ton diminished. He had become the sort of man everyone wished to invite to supper, but whom few wanted any deeper sort of connection to.

Regardless, he would not give up. London had been a failure for him, but perhaps he could visit the continent or the American colonies and find a willing bride there, one who was not overly concerned about being married to the man who created those sculptures.

“Oh, my lord.” Danforth stepped out into the hall, arresting Lawrence before he’d made it to the top of the stairs.

“Yes?” Lawrence asked, turning back to the man with a smile. He usually wore a smile, even though his brothers and cousins teased him for it. One could always smile, even when the world was sinking into a bog around him.

“Before you go, there is another letter for you waiting downstairs,” Danforth said. “It was just delivered by special courier, not more than ten minutes ago.”

“Thank you, Danforth,” Lawrence said, his smile going tight.

He turned and headed down the stairs, wondering which of the young ladies he’d spoken to at the opening of Joint Parliament the day before had turned down his request to call now.

But when he reached the table in the foyer where the silver salver that held correspondence rested, it was not another rejection from a lady that awaited him. Instead, the address on the envelope was written in the blocky, slightly splotched handwriting that most definitely belonged to a man.

Curious, he snatched up the envelope, broke the seal, then slowly, painstakingly, read its contents, his smile returning.

“ Godwin, I’ve had an inquiry from a gallery owner in Hamburg who would like to curate an exhibition of your sculptures based on the theme of the four seasons. He is deeply familiar with your work and will pay well. But he has one unique requirement. Please call upon me for more .”

It was sighed G. Loesser, the name of a friend and art broker Lawrence knew well.

“Excellent,” Lawrence said out loud, directing his comment to the two footmen who brought his traveling bags down while he’d been wrestling with the missive. “Hurry, hurry, lads. It appears as though I have a final errand to run before I’m through with London entirely.”

The footmen, kind, clever lads as they were, smiled at him as they carried his things out to the waiting carriage.

“Is this all of it, my lord?” Silas, his personal driver and sometimes valet, asked as he met the footmen at the door.

“It is,” Lawrence said, pausing to breathe in the cold, damp air as if it were the middle of summer. “As soon as it’s secured, we can go fetch Lady Minerva. Although I need to stop at Loesser’s offices along the way.”

Silas hummed and frowned, then said, “Begging your pardon, my lord, but the Oxford Society Club is on the way to Loesser’s gallery. If we go to the gallery then back again, it might take twice as long. I know you’re eager to be done with London.”

Lawrence sent Silas a kind smile. “You bring up a good point. Perhaps Lady Minerva would not mind attending this errand with me. We shall fetch her along the way, and then on to Loesser’s.”

“Very good, my lord.” Silas nodded and touched the brim of his hat, then held the door for Lawrence to hop into the carriage.

While Cedric detested it when his servants made suggestions and directed their master, Lawrence did not mind it at all. He trusted his servants. They’d been hired to do a job, and in almost every instance, they knew their job far better than he did. Because of that light hand with those many other gentlemen chose to command, most people, his family included, considered Lawrence to be weak of mind and even weaker of will.

Perhaps he was. He accepted what others thought of him without attempting to change it, and that made him seem a little too affable at times. But what point was there in attempting to change the ways of the world? The world was what it was, and as an artist, his job was to observe and render it in whatever medium he chose. It was not for him to change what God had made so perfectly.

The drive to the Oxford Society Club was uneventful. He was told that Lady Minerva had gone out on last-minute errands when he arrived, and since men were not permitted inside the club, except in the foyer, and only then when they were accompanied by a member of the club, and as the sky had begun to spit rain, he waited in his carriage until Lady Minerva made her appearance.

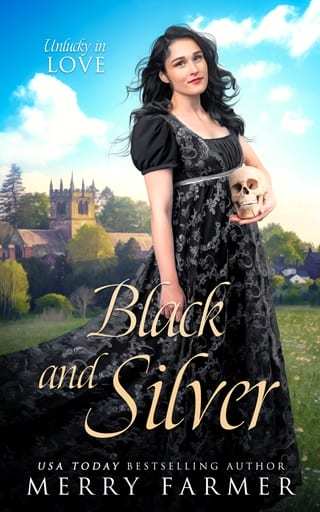

Lawrence nearly burst into laughter when she did finally appear. Lady Minerva was an enigma. No lady of her beauty and cleverness within the ton chose to dress as if she were a recent widow, the way Lady Minerva always did. Lawrence had always found that proclivity, and the sharp intelligence of the lady’s conversation, to be intriguing. When the opportunity had arisen for him to accompany Lady Minerva back to her home kingdom of Wales the day before, Lawrence had jumped at it. He needed to leave London anyhow, and Lady Minerva had provided him with the ideal excuse to flee.

And so he was in particularly good spirits when he stepped down from his carriage just as the lady passed and said, “Good day, Lady Minerva. Aren’t you looking fetching this fine morning.”

His words seemed to startle Lady Minerva far more than a greeting warranted. She grabbed his coat and dragged him towards the door of the club, hissing, “Hurry! Hurry! We mustn’t be seen at all.”

Lawrence nearly laughed at the excitement of it all. Lady Minerva already seemed to be caught up in some sort of fantasy, though Lawrence could not see why she would be so anxious to get off the street. No one around them was paying either of them the slightest bit of attention.

“Are we escaping from the law today or evading some criminal gang?” he asked as they stepped into the foyer of the Oxford Society Club.

Perhaps as expected, Lady Minerva narrowed her eyes at him in a disapproving scowl.

“Do you find something amusing in my wish to be discreet, Lord Lawrence?” she asked in clipped tones.

“Not at all,” Lawrence said, still trying to remain affable, as was his nature. “I love a bit of excitement in the morning. It makes the afternoon so much more restful when one has packed in their adventure before luncheon.”

A flat silence filled the space between Lawrence and Lady Minerva for a moment as she continued to stare at him.

Then she sucked in a breath, stood straighter, and tilted her chin up slightly.

“I am almost ready to depart, my lord,” she said, hugging her parcel closer. “If you will but give me ten minutes to complete the process and to have my things brought down, I shall be ready to venture out with you.”

“Of course, my lady,” Lawrence said, bowing gravely, though he couldn’t hide the delight he felt. The journey to Wales could take weeks, depending on the weather, and he would have the privilege of spending all that time with her.

Lady Minerva left him, and Lawrence was politely asked to step outside once more. The rain had picked up a slight bit, but he did not hide away in his carriage as he could have.

Instead, as soon as Lady Minerva emerged with a rather large valise, he rushed to assist her.

“Allow me, my lady,” he said, smiling despite the rain.

“I can manage quite well on my own,” Lady Minerva snapped in return.

Her attempt at independence, and Lawrence was certain that’s what it was, which he could easily forgive her for, was marred slightly by the alert way she glanced up and down the street before handing her valise off to Silas in order for him to add it to the trunk at the back of the wagon. She continued to search the area as Lawrence offered her a hand to step into the carriage. Once she was seated, she tucked herself into the far corner of the rear-facing seat and hugged her black coat around her.

“I say,” Lawrence joked, looking up and down the street himself, then pretending to peer blindly into the carriage without seeing much. “Silas, have you seen Lady Minerva Llewellyn? I swear, she was here a moment ago, but she seems to have disappeared entirely.”

“Must you?” Lady Minerva sighed over his antics.

“Oh! There you are,” Lawrence said, stepping into the carriage and sitting on the forward-facing seat. “You veritably blend into the shadows in that coat.”

“Yes, well, sometimes it is best to blend into the shadows,” she said frostily.

Lawrence laughed softly and settled himself in as Silas finished with the trunk, then took his seat atop the carriage and nudged the horses onward.

“Oh, I should beg your pardon, my lady,” Lawrence said once they were moving safely along the road. “I have a final errand I must attend to before we take to the western road.”

“An errand?” Lady Minerva asked with far too much alarm. “Where? In the city?”

“In Marylebone, actually,” Lawrence said. “Not much farther on than here. A friend of mine who is an art broker sent me a letter just before I left the house an hour ago, informing me of a gallery in Hamburg that wishes to stage an exhibition of my work.”

Lady Minerva’s entire countenance changed as she blinked and sat straighter. “I’d forgotten you were an artist, my lord. My friends who have married into your family told me, of course, but I am sorry to say that I cannot recall ever seeing any of your paintings displayed.”

“Sculptures,” Lawrence said, blushing a bit. “I am predominately a sculptor. Though I do sketch quite a bit while doing studies for my pieces.”

“Sculptor, then,” Lady Minerva said with a nod. “Are you in the National Gallery?”

Lawrence cleared his throat. “Er, no. My sculptures are more for…private audiences.”

For the first time since fetching her, Lawrence caught a sparkle in Lady Minerva’s eyes. “I am intrigued, my lord.”

“As all good minxes are,” Lawrence answered her cheekily.

That caused Lady Minerva to tense up and hug herself tighter again.

“I beg your pardon, my lady,” Lawrence said, wincing. “I should not have presumed to jest with you so early in our acquaintance. I think you will find that I frequently make the wrong comment at the wrong moment. It is just that I find society to be so unbearably stuffy and restrained sometimes. Life is enjoyable. I cannot fathom why people hide from that so much.”

Lady Minerva waited far too long, staring at him, before saying, “Indeed.”

The conversation faltered from there. A few things were said about the weather and about the length of the journey as they traveled on to Loesser’s office, but not much.

Lawrence gave Lady Minerva the option of waiting in the carriage while he stepped inside to see what the details of the deal Loesser wanted to work out for him were, but she declined. That came as a bit of a surprise, but perhaps not as much as it could have when Lady Minerva rushed straight from the carriage and into the office building, pulling her bonnet down over her face, lest anyone passing recognize her.

“You are beginning to make me think you are some sort of spy, my lady,” Lawrence whispered as they approached the desk at the front of the office.

“No, you have me confused with my friend, Lady Kat,” Lady Minerva said, sending Lawrence a sideways look.

Lawrence’s heart lifted. It appeared Lady Minerva did have a sense of humor after all.

“Ah, Lord Lawrence, welcome,” Loesser said, stepping out of the back room and up to the other side of the desk. “That was quick.”

“I am about to depart London,” Lawrence said, reaching across to shake Loesser’s hand. “You might not be able to reach me for a few weeks, until I arrive at Godwin Castle after returning Lady Minerva Llewellyn to her home kingdom.”

“My lady,” Loesser greeted Lady Minerva with a nod and a smile.

Lady Minerva smiled briefly at him, then returned to looking around the front room of the office, which was filled with various artwork.

“About this Hamburg offer,” Lawrence said.

“Yes, I knew you’d be interested,” Loesser said with a wink. “It’s for one of the more progressive galleries in the city. They wish to do an entire exhibition of your work.”

“That’s splendid,” Lawrence said, beaming. “I suppose if one cannot be appreciated in his own country, the next best thing is to gain a following somewhere else.”

“It certainly is,” Loesser said. “And they’re willing to pay a pretty penny for the privilege of displaying your art, and perhaps selling a few pieces, if the opportunity arises.”

“I would be amenable to that,” Lawrence said. “Whatever of mine that you do not already have in your storerooms, I could have fetched for you from my studio in Winchester.”

“Perfect,” Loesser said. He then pinched his face and added, “There’s only one complication.”

“Oh?”

Lawrence glanced to the side at Lady Minerva’s sudden intake of breath. He was more than a little alarmed to find one of his own, particularly erotic sculptures sitting out on a table near the window. Whatever hope Lawrence had that Lady Minerva had spotted whatever she’d been looking for outside the window and that that was what had caused her gasp was thwarted when he saw her clap a hand to her mouth as she looked at the carved man and woman in a particularly amorous embrace in marble form.

“The gentleman in Hamburg remembers a particular sculpture of yours,” Loesser went on, either not seeing Lady Minerva’s reaction or being so accustomed to the shock of ladies over art that he paid it no mind. “Primavera in Splendor.”

Lawrence snapped his attention away from Lady Minerva and stared with wide eyes, face heating, at Loesser.

“Primavera in Splendor?” he asked, his voice hoarse and cracking.

“Yes,” Loesser said with a knowing smirk. “It’s one of your finest works.”

“I, er, thank you?”

“The Hamburg gentleman is interested in purchasing it from you after the gallery show. For a thousand guineas.”

“My God!” Lady Minerva gasped, twisting to face him.

“A thousand guineas?” Lawrence repeated. “For that old thing?”

“It seems he has never forgotten it, even though he first laid eyes on it ten years ago,” Loesser said. “Do you think you can procure it for him?”

Lawrence was silent for a long time, thinking about it. He would have loved nothing more than to rid the island of Britannia of that particular statue, and the memories behind it, forever. If he’d had it in his possession, he would have sent for it at once. He might have even given it the Hamburg gentleman for no price at all, just so that he would never see it again. Or more importantly, that its current owner would never see it again.

“The work in question is not in my possession at the moment,” he said carefully.

“I know,” Loesser said, grinning. “Lady Wimpole still has it, doesn’t she.”

Lawrence swallowed tightly. “She does, though she has remarried and is no longer Lady Wimpole.”

Loesser shrugged. “So get it back from her, whatever she’s called these days,” he said. “Something tells me she wouldn’t put up that much of a fuss, if she even still has it. Especially if she’s remarried. If her new husband even knows the statue exists, I bet he’d be grateful to be rid of it as well.”

“Indeed,” Lawrence said.

“Where does this former Lady Wimpole live?” Lady Minerva asked, coming forward, even though part of Lawrence wished she hadn’t.

“Er, Wiltshire,” Lawrence said.

“How convenient,” Lady Minerva said. “Wiltshire is on the way to Wales. We could stop at no-longer-Lady Wimpole’s house and ask for the statue back.”

“Yes, we could,” Lawrence said, slowly and reluctantly.

“A thousand guineas,” Loesser reminded Lawrence. “I could use the commission for a sale like that.”

Lawrence let out a sigh, lowering his shoulders. Loesser had a point. A thousand guineas would not make or break him one way or another, but for a man who lived on such close margins as Loesser, it could mean a great deal.

“Alright,” Lawrence said with a shrug. “I do not suppose it could hurt to visit Wiltshire and inquire whether Lady Wimpole still possesses the statue.”

“Good man,” Loesser said, reaching across the counter to thump Lawrence’s arm. “I knew you’d be willing to help a friend out.”

“Yes,” Lawrence said with a smile.

Deep down, however, he wondered if his willingness to go out of his way for the benefit of others was one of the reasons so many people considered him to be so simple. One way or another, time would tell.

Fullepub

Fullepub