Chapter 13

Thirteen

The rain would not let up, the cottage seemed to take forever to heat, and time became Lawrence’s enemy as he waited for Silas to return from whatever village he’d seen in the distance. Lawrence was loath to let Minerva out of his sight, even though she’d fallen into a deep sleep, but he was desperate enough, in his bare feet and minimal dress, to don his things again so that he could walk out to the carriage to retrieve some of his and Minerva’s baggage.

It was a terrible idea. The rain pounded mercilessly down. Without Silas there to help, he had to struggle with the trunk that contained their smaller trunks and bags on the back of the carriage. He dropped his small trunk into the mud of the insufficient stable structure and nearly spooked one of the horses into bolting in the process. The only thing that prevented the horse from fleeing in disgust was what Lawrence assumed was its own exhaustion and misery.

He did eventually manage to bring enough baggage into the house to strip down and wash completely, including his hair, dry himself, and dress in fresh, dry clothing. It was bliss.

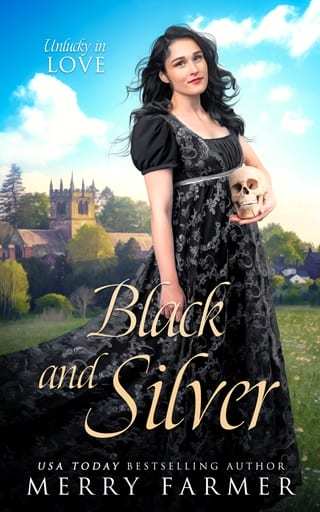

That momentary relief faded quickly when he returned to sit by Minerva’s bedside. He’d fetched Clarence from the carriage along with his things, and with more seriousness than he supposed he should have used, he set the skull on the bedside table to watch over her along with him.

Minerva was so pale, and yet fever painted her beautiful cheeks. Her breaths were long and deep, but they had the strain of someone who was not well to them. She coughed a few times without waking, and Lawrence could tell that her throat was still very sore.

It was agony to have nothing to do but watch as whatever malevolent spirit that had ahold of Minerva tortured her. He adjusted her blankets and tested her skin in an attempt to determine whether she was too hot several times. He paced back and forth in the main room, finally setting the kettle to boil when the stove was hot enough, but then returning to watch Minerva a bit longer rather than staring at the water.

The afternoon wore into a gloomy evening, and Lawrence’s patience wore so thin that he set himself the task of washing Minerva’s hair for her without waking her. He carried a basin he’d found with clean, warm water to the side of the bed, lifted Minerva enough to layer towels under her head, then attempted to sponge and comb water through her hair until the mud came out and the water ran clean.

He succeeded in improving her condition a bit, but not in allowing her to sleep on.

“What are you doing?” she asked, her voice decidedly scratchy, when his ministrations disturbed her.

“Attempting to wash your hair,” Lawrence said, smiling at her and stroking the backs of his fingers across her face. He could not help but touch her, although, should she ask, he would say he was testing for fever.

“You’ve changed,” she said, struggling to push herself to sit.

“No, no, I am the same ridiculous oaf I’ve always been,” Lawrence said, attempting to smile.

Minerva let out a breath and sent him a sideways half-grin that nearly had Lawrence’s heart beating out of his chest.

That moment of elation was dampened when she began to cough, then groaned and clutched at her throat to indicate the pain she was in.

“I brought Clarence in to nurse you, and I made tea,” Lawrence announced, leaping frantically up from the bed, desperate to do whatever he could to ease her suffering. If there was a dragon outside the cottage that needed battling, he would have rushed to defeat it. “I’ll make you some more with honey.”

Minerva nodded, but rather than resting and letting him get on with things, she pushed and struggled to get out of bed.

“I beg your pardon, madam,” Lawrence said, turning back and blocking her way. “What do you think you’re doing?”

“Getting up,” Minerva croaked. Lawrence opened his mouth to protest, but Minerva countered him with, “I wish for more than my hair to be clean. You’ve obviously taken a bath, so I would like one as well.”

Lawrence blew out a breath and let his arms drop, defeated. He could not very well deny her the same pleasure he’d given himself. Not when he could see how musty she still was from the mud.

Against his better judgment, but eager to please her as well as protect her, Lawrence helped Minerva rise and return to the cottage’s main room. It was considerably warmer than before, and although Minerva was still shivering and unsteady on her feet, the room was more comfortable for her.

Even ill, Minerva was stubborn. As much as Lawrence tried to hover and assist her, she insisted that she was fully capable of bathing herself. She batted away Lawrence’s every attempt to help her undress or soap up the sponge he’d used earlier on her hair. He conceded defeat when she asked him to turn around while she accomplished the actual bathing, but unbeknownst to her, he watched her reflection in the cottage’s windows to make certain she did not struggle unduly.

He insisted on helping Minerva to dry off, though he still kept his eyes averted, and then put his foot down and carried her back to bed.

“This is all entirely unnecessary,” she croaked as he fed her honeyed tea and broth he’d made from a jar of bouillon paste he’d found in the pantry, along with a bit of bread that had gone stale, but was not yet moldy. “I can feed myself.”

“Can you?” Lawrence asked, one eyebrow arched scoldingly. “Clarence doesn’t think so.”

He glanced to the skull, then nodded, as if Clarence had stated his agreement.

Minerva merely looked at him with a stare that would have made evil spirits shudder in their boots, but that quickly dissolved into a sigh.

“The two of you have joined forced against me,” she said.

Worryingly, she only finished half her meal, then settled down to sleep without a fuss afterwards. Her slumber was heavy right from the start, though she continued to cough and shiver, even as she snored.

Lawrence returned to pacing, consumed with the desperate need to do something. He felt very much as if he would go out of his mind if Minerva did not turn a corner soon.

A small bit of relief came when Silas returned to the house about an hour after dark.

“There’s a wainwright in the village,” he announced, his voice thick with exhaustion, as he removed his coat and hat. “He’s happy to repair the carriage, but he requested that I bring it there on the morrow.”

“Will the carriage make the journey?” Lawrence asked.

Silas nodded, but without confidence. “If we unload it to put as little strain on the axle as possible,” he said. “It’s merely cracked, not broken yet.”

“We’ll remove the statue before you leave,” Lawrence said. A half-smile flitted across his face before he said, “We can store it in the church until we’re ready to move on.”

Silas laughed at whatever picture that suggestion created in his mind.

His expression lightened for a moment before he went on to say, “Oh, you’ll be pleased to know, my lord, that I asked about the parson at the village. He’s away visiting relatives in Winchester until the end of the month. He only just left the day before yesterday.”

“Which explains why there is still bread and a bit of milk in the house,” Lawrence said, grateful for it.

Silas nodded. “I’ll fetch more provisions in the morning, when I take the carriage to the village. And I was told there’s a village wise woman who might be able to dose Lady Minerva with some sort of healing tincture as well.”

“Thank God,” Lawrence breathed out. “I’d prefer a London physician, but between you and me, it is often these village healers that do a better job of it while causing less damage to their patients.”

Silas agreed with a nod, and the two of them set to work making pallets for them to sleep on for the night. Lawrence supposed he could have attempted to share the bed with Minerva, but he did not want her to wake in the night and fear he had undertaken any sort of impropriety with her.

Not that Lawrence had much rest that night. Every time Minerva so much as sniffled, he leapt up and ran to her bedside to see what was the matter. He went running so much that halfway through the night, he moved his pallet into the bedroom to sleep on the floor by her side.

In the morning, the rain had gone, but Minerva’s fever was hotter than ever. So much so that she barely stirred when Lawrence hovered over her, pressing the back of his hand to her forehead.

“I wish I’d paid more attention to whatever malady that was at the quarantined inn we passed,” Lawrence worried aloud as he stood over her.

“Er, it was a putrid fever, my lord,” Silas answered from the other side of the bedroom doorway. “Some of the others in the stable, where I passed the night, said three or four people had already died of it.”

Lawrence caught his breath. That was not what he wanted to hear.

“Fetch the wise woman, then, Silas, if you please,” he said.

“As soon as you help me unburden the carriage, my lord.”

Lawrence winced. He hated leaving Minerva’s side, but the quicker they managed to complete the task, the sooner Minerva would have help.

The rain had stopped, but the roads and paths around the parsonage and the church were still muddy and slippery. On any other day, Lawrence would have laughed uproariously at the way he and Silas struggled with his lurid statue as they carried it from the carriage to the church. Silas only dared to drive the carriage as far as the road, rather than all the way to the church door, which meant the two of them had to struggle through the mud before carrying the heavy carving into the church.

As it happened, some of the mud splashed to a particular spot near the backside of the male figure in the arrangement, giving the appearance of the whole a completely different connotation. Lawrence prayed that Minerva would recover soon enough to come view the statue where they placed it, atop the baptismal font, with the mud lodged in its current crack.

As hopeful as Lawrence was once Silas drove away with the carriage, being without conveyance in a strange place, while the woman he was willing to admit he adored above all others lay abed with an affliction that was known to have ended lives, had Lawrence feeling restless and anxious.

He did whatever he could think of to combat his anxiety, bringing firewood into the house to dry after the night’s rain, searching the cupboards for anything resembling food and attempting to cook, and even fetching one of Minerva’s books of poetry and submitting himself to the extreme pain of attempting to read it.

All of his activities did nothing to ease his troubled mind, so when the grey-haired old matron who professed herself to be the village healer arrived at the parsonage door, Lawrence nearly wept with relief.

“How long has she been like this?” the old woman asked as she leaned over a fitfully sleeping Minerva, pressing her hand to Minerva’s face.

“I believe she began to take ill yesterday morning,” Lawrence said, “then progressively became worse throughout the day. She washed up before bed last night, but she has not truly been sensible at all yet today.”

That worried him enough, since he was sure it was close to midday, but when the old woman made a dire sound, his nerves all but shattered.

“It’s the wasting fever, to be sure,” she said, turning away from the bed and shaking her head. “It’s been scourging the countryside these last few weeks, taking young and old indiscriminately. I am sorry, my lord.”

Lawrence had to fight not to yelp. “Is there nothing you can give her for it?” he asked. “No tea or tablet or tincture?”

The old woman shrugged, then gestured for him to follow her into the main room. “I’ve got herbs for a tea, if she’s well enough to drink it. Otherwise,” she shrugged, “it’s up to the will of God.”

“But there must be something that could help,” Lawrence fretted.

“Not with a fever like this,” the woman said.

Lawrence was in no way satisfied with that answer. Someone somewhere must have had the ability to do something.

A flash of inspiration hit him. “My father will know what to do,” he said, speaking more to himself than the old woman. “He has lived a long time and suffered more than his fair share of illness. He would know what the cure for this particular fever might be.”

“I could have him fetched,” the old woman said.

Lawrence winced. “He’s all the way down at Godwin Castle, on the Isle of Portland.” He paused, then said, “Truly, we should travel there, to him. I would feel far safer if my Minerva could convalesce in my family home.” He would most certainly be able to find a more competent physician to attend her there.

“You could write to him, explain the situation and tell him you and your lady are on your way, though whether she lasts that long is up to God, not us,” the old woman suggested. “I’ll see that the letter is delivered.”

A deeper sort of distress struck Lawrence. Of all the times for the one skill he had never mastered to be the singular one he needed, it had to be now.

He was too desperate for Minerva to be well to hold onto his pride, so he admitted to the woman, “I cannot write.”

The old woman stared at him for a moment before saying, “Then you’re lucky I can.”

She toddled off to the side, to a desk in the corner, as if she’d been in the parsonage before and knew where things were. She helped herself to the chair, then produced a piece of paper from one of the cubbies and a bottle of ink from another.

Lawrence paced behind her as she wrote. He wondered if he had just fallen victim to the Curse of Godwin Castle. Surely, that was the devilry behind Minerva’s illness. It was the curse, he was certain, that had led to him being so unlucky in love thus far in his life. The curse had thrown him together with Minerva precisely at the point when something as pedestrian as a fever would take her from him.

If it was the last thing he did, as soon as Minerva was well enough, he would marry her and…and doom Dunstan to suffer with the curse alone?

He could not worry about his cousin just yet. In the moment, Minerva was the only one he could have a care for.

“There,” the wise woman said, finishing the letter, then presenting him with the pen. “Can you sign your name or make your mark?”

“Yes, I can,” Lawrence said. He rushed forward, took up the pen, and scribbled his name across the bottom of the paper.

Only after the wise woman sanded and blotted the letter, then folded it and wrote the address of Godwin Castle as Lawrence dictated it did Lawrence consider that he should have at least made an attempt to read the letter’s contents first. He’d instructed the old woman to plead the necessity of sending help, as he figured that was all that was needed.

“Make certain that reaches Lord Gerald Godwin as quickly as possible,” he charged the old woman as he escorted her out of the house. “And if you can think of anything at all that might aid Lady Minerva in her recovery, please return and share it.”

“I will, my lord, but I think it’s best that you prepare yourself.”

Lawrence wanted to rage with frustration at those words. How could Minerva be so close to death already when less than two days ago, they were creeping through Tidworth Hall’s attic, then tangled up in the throes of passion? It made no sense at all to him.

At least the old woman was sympathetic, even if she was a harbinger of doom.

“I’ll have one of my girls come by with a basket of provisions for you,” she said, patting Lawrence’s arm sympathetically as she stepped out of the cottage. “You won’t have to leave her side until the end.”

Lawrence huffed in annoyance, then immediately felt guilty and schooled his expression to one of thanks. “I cannot express my gratitude,” he told the woman with a smile as she turned to walk off.

He could not express it, because he was not convinced he had any. At least, he was not convinced the old woman had done anything but worry him needlessly.

Minerva would not perish. He would not let something as mundane as a fever take her. Minerva was strong and imaginative. If she were to die at all, it would be because she was struck by lightning or lost at sea, or some other means of shuffling off her mortal coil that would be worthy of the sort of tale she liked to read.

There had to be something he could do.

Lawrence shut the cottage door, then returned to the bedroom, where Minerva continued to slumber. He sat on the edge of the bed, aching with exhaustion himself, and sought out her hand as it lay on the covers.

“All will be well, my darling,” he said, stroking the back of her hand as he held it in one of his. “This is just a passing fever. You will be right as rain, standing in the cemetery, making up macabre tales of its inhabitants again in no time.

Minerva gave a short, sniffling breath, then coughed without waking. Lawrence’s heart squeezed, threatening to break within him. He glanced to Clarence as if appealing to a friend. This could not be the end, it simply could not.

Fullepub

Fullepub