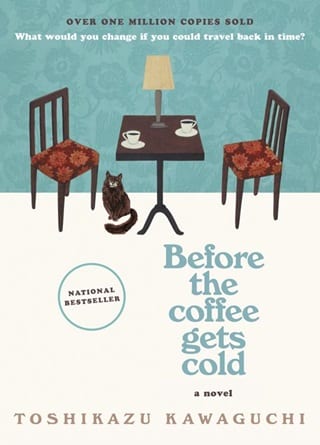

Excerpt from Tales from the Cafe by Toshikazu Kawaguchi

Tales from the Cafe

by Toshikazu Kawaguchi

i

Best Friends

Gohtaro Chiba had been lying to his daughter for twenty-two years.

The novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky once wrote, “The most difficult thing in life is to live and not lie.”

People lie for different reasons. Some lies are told in order to present yourself in a more interesting or more favorable light; others are told to deceive people. Lies can hurt, but they can also save your skin. Regardless of why they are told, however, lies most often lead to regret.

Gohtaro’s predicament was of that kind. The lie he had told plagued him. Muttering things to himself, such as “I never wanted to lie about it,” he was walking back and forth outside the café that offered its customers the chance to travel back in time.

The café was a few minutes’ walk from Jimbocho Station in central Tokyo. Located on a narrow back street in an area of mostly office buildings, it displayed a small sign bearing its name, “Funiculi Funicula.” The café was at basement level, so without this sign, people would walk by without noticing it. Descending the stairs, Gohtaro arrived at a door decorated with engravings. Still muttering to himself, he shook his head, swung round and began walking back up the stairs. But then he suddenly stopped with a thoughtful expression on his face. He went back and forth for a while, climbing the stairs and descending them.

“Why not stew over it after you come in?” said a voice abruptly.

Turning around, startled, Gohtaro saw a petite woman standing there. Over her white shirt she was wearing a black waistcoat and a sommelier’s apron. He could tell instantly she was the café’s waitress.

“Ah yes, well...”

As Gohtaro began to struggle with his response, the woman slipped past him and briskly descended the stairs.

clang-dong

The ring of a cowbell hung in the air as she entered the café. She hadn’t exactly twisted his arm, but Gohtaro descended once again. He felt a weird calmness sweep over him, as if the contents of his heart had been laid bare.

He had been stuck walking back and forth because he had no way of being certain that this café was actually the café “where you could return to the past.” He’d come there believing the story, but if the rumor his old friend had told him was completely made up, he would soon be one very embarrassed customer.

If traveling back to the past was indeed real, he had heard there were some annoying conditions that you had to follow. One was that there was nothing you could do while in the past that would change the present, no matter how hard you tried.

When Gohtaro first heard that, he wondered, If you can’t change anything, why would anyone want to go back?

Yet he was now standing at the front door of the café thinking, Even so, I want to go back.

Had the woman read his mind just now? Surely a more conventional thing to say in that situation would be, Would you like to come in? Please feel welcome .

But she had said, Why not stew over it after you come in?

Perhaps she meant: yes, you can return to the past, but why not come inside first before deciding whether to go or not.

The bigger mystery was how the woman could possibly know why he had come. Yet he felt a flicker of hope. The woman’s offhand comment was the trigger for him to make up his mind. He reached out, turned the doorknob, and opened the door.

clang-dong

He stepped into the café where, supposedly, you could travel back in time.

Gohtaro Chiba, aged fifty-one, was of stocky build, which was perhaps not unrelated to him having belonged to the rugby club in high school and at university. Even today, he wore an XXL-sized suit.

He lived with his daughter Haruka, who would be twenty-three this year. Struggling as a single parent, he had raised her alone. She had grown up being told, Your mother died of an illness when you were little . Gohtaro ran the Kamiya Diner, a modest eatery in the city of Hachioji in the Greater Tokyo Area. It served meals with rice, soup and side dishes, and Haruka lent a hand.

Entering the café through the six-foot-high wooden door, he still had to pass through a small corridor. Straight ahead was the door to the toilet, in the center of the wall to the right was the entrance to the café. As he stepped into the café itself, he saw a woman sitting at one of the counter chairs. She instantly called out, “Kazu...customer!”

Sitting beside her was a boy who looked about elementary school age. At the far table sat a woman in a white short-sleeved dress. With a pale complexion and a complete lack of interest in the world around her, she was quietly reading a book.

“The waitress just got back from shopping, so why don’t you take a seat. She’ll be out soon.”

Obviously caring little for formalities with strangers, she spoke to Gohtaro casually, as if he was a familiar face. She appeared to be a regular at the café. Rather than replying, he just gave a little nod of thanks. He felt the woman was looking at him with an expression that seemed to say, You can ask me anything you like about this café . But he chose to pretend he hadn’t noticed and sat down at the table closest to the entrance. He looked around. There were very large antique wall clocks that stretched from floor to ceiling. A gently rotating fan hung from where two natural wooden beams intersected. The earthen plaster walls were a subdued tan color, much like kinako , roasted soya flour, with a hazy patina of age—this place looked very old—spread across every surface. The windowless basement, lit only by shaded lamps hanging from the ceiling, was quite dim. The entire lighting was noticeably tainted with a sepia hue.

“Hello, welcome!”

The woman who had spoken to him on the stairs appeared from the back room and placed a glass of water in front of him.

Her name was Kazu Tokita. Her midlength hair was tied back, and over her white shirt with black bow tie she wore a black waistcoat and a sommelier’s apron. Kazu was Funiculi Funicula’s waitress. Her face was pretty with thin almond eyes, but there was nothing striking about it that might leave an impression. If you were to close your eyes upon meeting her and try to remember what you saw, nothing would come to mind. She was one of those people who found it easy to blend in with the crowd. This year she would be twenty-nine.

“Ah...um... Is this the place...that er...?”

Gohtaro was completely lost as to how to broach the subject of returning to the past. Kazu calmly looked at him fluster. She turned toward the kitchen and asked, “When do you want to return to?”

The sound of coffee gurgling in the siphon came from the kitchen.

That waitress must be a mind reader...

The faint aroma of coffee beginning to drift through the room sparked his memory of that day .

It was right in front of this café that Gohtaro met Shuichi Kamiya for the first time in seven years. The two had been teammates who played rugby together at university.

At the time Gohtaro was homeless and penniless, having been forced to surrender all his assets—he had been the co-signer on a loan obligation for a friend’s company that had gone bankrupt. His clothes were dirty, and he reeked.

Nevertheless, instead of being disgusted by his appearance, Shuichi looked genuinely pleased to have met him again. He invited Gohtaro into the café, and after hearing what happened, proposed, “Come and work at my diner.”

After graduation Shuichi had been scouted for his rugby talent by a company in a corporate league in Osaka, but he hadn’t played even one year before an injury cut short his career. He then joined a company that ran a restaurant chain. Shuichi, the eternal optimist that he was, saw this setback as a chance, and by working two or three times as hard as everyone else he rose to become an area manager in charge of seven outlets. When he got married, he decided to strike out on his own. He started a small Japanese restaurant and worked there with his wife. Now he told Gohtaro that the restaurant was busy and that some extra help would be welcome.

“If you accepted my offer, it would be helping me out too.”

Run down by poverty and having lost all hope, Gohtaro broke down in tears of gratitude. He nodded. “Okay! I’ll do it.” The chair screeched as Shuichi stood up abruptly. Grinning cheerfully, he added, “Oh, and wait till you see my daughter!”

Gohtaro still wasn’t married and he was a little surprised to hear that Shuichi had a child.

“Daughter?” he responded with his eyes widening.

“Yeah! She’s just been born. She is so—cute!”

Shuichi seemed pleased with Gohtaro’s response. He took the bill and strolled over to the cash register. “Excuse me, I’d like to pay.”

Standing at the register was a fellow about high-school age. He was very tall, close to six feet in height, and had distant, thin almond eyes.

“Comes to seven hundred and sixty yen.”

“Here, from this please.”

Gohtaro and Shuichi were rugby players and bigger than most, but they both looked up at the young fellow, then looked at each other, and laughed, probably because they were thinking the same thing, This guy is built for rugby .

“And here’s your change.”

Shuichi took the change and headed for the exit.

Before he was homeless, Gohtaro was quite well-off, having inherited his father’s company that made over one hundred million yen a year. Gohtaro was a sincere kind of guy, but money changes people. It put him in a good mood, and he started squandering it. There was a time in his life when he thought that if you had money, you could do anything. But his friend’s company to which he had co-signed as guarantor folded, and after being hit with this huge debt obligation his own company went under too. As soon as his money was gone, everyone around him suddenly started treating him like an outcast. He had thought those close to him were his friends, but they deserted him, one even saying openly to his face, What use are you without money?

But Shuichi was different; he treated Gohtaro, who had lost everything, as important. People willing to help someone struggling, without expecting anything in return, are rare indeed. But Shuichi Kamiya was one such person. As he followed Shuichi out of the café, Gohtaro was adamant in his resolve: I’ll repay this favor!

clang-dong

“That was twenty-two years ago.”

Gohtaro Chiba reached for the glass in front of him. Wetting his parched throat, he sighed. He looked young for fifty-one, but a scattering of grey hairs had begun to show.

“And so, I started to work for Shuichi. I put my head down and tried to learn the job as fast as I could. But after a year, there was a traffic accident. Shuichi and his wife...”

It had happened more than twenty years ago, but the shock of it had never left him. His eyes reddened and he began choking on his words.

Sluurrrp!

The boy sitting at the counter began noisily sucking the final drops of his orange juice through his straw.

“And what happened then?” Kazu asked matter-of-factly, not pausing in her work. She never changed her tone no matter how serious the conversation. That was her way of keeping herself at a distance from people, perhaps.

“Shuichi’s daughter survived, and I decided to bring her up.”

Gohtaro spoke with his eyes cast down as if muttering to himself. Then he stood up slowly.

“I beg of you. Please let me go back to that day twenty-two years ago.”

He bowed long and deep, bringing his hips to a near right angle and dropping his head lower.

This was the café Funiculi Funicula. The café that became the subject of an urban legend some ten years ago as being the one where you could go back in time. Urban legends are made up, but it was said that at this café, you could really return to the past.

All sorts of tales are told about it, even today, like the one about the woman who went back to see the boyfriend she had split up from, or the sister who returned to see her younger sister, who had been killed in a car crash, and the wife who traveled to see her husband who had lost his memory.

In order to go back to the past, however, you had to obey some very frustrating rules.

The first rule: the only people who you can meet while in the past are those who have visited the café. If the person you want to meet has never visited the café, you can return to the past, but you cannot meet them. In other words, if visitors came from far and wide across Japan, it would turn out to be a wasted journey for practically all of them.

The second rule: there is nothing you can do while in the past that will change the present. Hearing this one is a real letdown for most people and normally they leave in disappointment. That is because most customers who want to return to the past are wishing to fix past deeds. Very few customers still want to travel back after they realize they can’t change reality.

The third rule: there is only one seat that allows you to go back in time. But another customer is sitting on it. The only time you can sit there is when the customer goes to the toilet. That customer always goes once a day, but no one can predict when that will be.

The fourth rule: while in the past, you cannot move from your seat. If you do, you will be pulled back to the present by force. That means that while you are in the past, there is no way to leave the café.

The fifth rule: your stay in the past begins when the coffee is poured and must end before the coffee gets cold. Moreover, the coffee cannot be poured by just anybody; it must be poured by Kazu Tokita.

Regardless of these frustrating rules, there were customers who heard the legend and came to the café asking to go back in time.

Gohtaro was one such person.

Fullepub

Fullepub