Chapter 2

2

Mathilda : Is life always this hard, or is it just when you’re a kid?

Léon : Always like this.

— The Professional

West Village, Manhattan

Earlier That Day

The timer goes off, the blare of it snapping me out of the trance induced by the rhythmic tapping of the jump rope. I stoop to pick up my phone from the surface of the roof and shove it into the pocket of my hoodie, gaze out over the rooftops of the West Village, and breathe in the brittle air.

It’s a beautiful day.

Down the stairs and back in my apartment, I hang the jump rope from its hook next to the door. P. Kitty waddles over to his food dish in the kitchen and yowls, demanding tribute. I pull out a can of chopped chicken hearts and liver and dump it into his dish, give him a little scratch on the top of his big dumb orange head as he shoves his face into the bowl.

Part of me wants to stay home and watch movies and take a night off from processing deep emotions, but Kenji will be waiting for me at Lulu’s and I don’t want to stand him up. That’s enough to get me in gear. The temperature is somewhere in the twenties, but ten minutes of jumping rope is still enough for a sweat, so I hop in the shower, rinse, and get dressed. Then I make sure P. Kitty’s water is filled. He ate half his food and retired to the couch, transformed into a shapeless ball of orange fur.

“No parties while I’m out,” I tell him.

He doesn’t stir.

I grab the trash and head for the door, then realize I forgot my notebook. It’s on top of my tattered, beaten copy of the Big Book—the textbook for Alcoholics Anonymous—which is in its spot of reverence, next to the paper crane Kenji gave me in Prague all those years ago. I tuck the notebook into the pocket of my jacket and feel a bit safer.

The window is open a crack—the apartment holds heat like a pizza oven—but it looks too narrow for P. Kitty to wriggle through, and I’d rather not come home to a sauna, so I leave it.

I walk down a floor and knock on the door of the apartment directly below me. There’s a shuffling sound from the other side, and the door cracks open, an eye peering out at chest level. It widens with recognition and Ms. Nguyen opens the door. She’s wearing a heavy bathrobe and fuzzy slippers, her gray hair pushed flat against her scalp by a red headband.

“Trash service,” I tell her.

Her face breaks into a smile as she holds up a small white plastic bag tied neatly at the top. “You’re so sweet.”

“Call it even for feeding my cat while I’m away. But you have to cool it on the treats. He’s getting chubby.”

“He’s not chubby, he’s big-boned,” she says. “And if he’s looking for food, it means he’s hungry. You don’t feed him enough.”

“Agree to disagree.”

“Do you need me to watch him over Christmas? Are you going anywhere?”

“I’ll be the same place I am every year. Upstairs, drinking whiskey, watching It’s a Wonderful Life .”

“No family, no girlfriend?” she asks. “Or boyfriend?”

I shrug. “I don’t do Christmas. I didn’t get the BMX bike I asked for when I was a kid. It went downhill from there.”

“Okay, Scrooge, I’ll be making almond cookies for my son and his kids on Christmas Eve if you want to stop by.” She raises an eyebrow. “I could use a strong set of hands.”

“Doesn’t matter how many times you hit on me, I’m not going to sleep with you.”

She laughs and reaches up to smack me on the chest. “Like you would be so lucky. Thanks for taking the trash, Mark.”

“See you tomorrow, darling,” I tell her, heading for the stairs. “And stop sneaking food to my cat.”

She calls after me: “Stop starving him.”

I hit the street and drop the trash in the bins, then point myself toward the Lower East Side. Normally I would walk but at this point it’s probably better to take the F, so I hustle over to West Fourth, then run down the stairs and manage to jump on a car as the doors are closing.

And of course, there’s Smiley.

Smiley is a regular in this neighborhood. Not always the F, I’ve seen him on the A and the 1, too. He may live around here, or else it’s just his hunting ground. As per usual he’s swaying out of time with the rocking of the subway car, clutching a half-empty bottle of Hennessy, oozing with mid-twenties bravado. His unkempt hair is greasy, and then there are those ever-present scars on his face. One across each cheek, lending him the appearance of a grotesque smile.

My tack has always been to ignore him. Most people causing a stir on the subway are homeless or mentally ill, and I have sympathy for them; the city spends billions on the NYPD, which doesn’t do much more than corral, harass, or beat them. And it gets that money by gutting the homeless and mental wellness agencies that could actually help them.

By and large, they’re more a danger to themselves. If you ignore them, they leave you alone, and you can always get on the next car or wait for the next train.

But that’s easy for me to say.

Right now he’s talking at a pretty young brunette in expensive leather boots and a white bubble jacket. She is not picking up what he’s putting down. Rather, her body is curled in on itself, like she’s trying to make herself disappear. Fear permeates the car, people looking away, like maybe if they don’t see it they don’t have to feel guilty.

I sit in the empty seat next to her, but I look up at Smiley. “Hey, bud. What’s your favorite ice cream flavor?”

The record in his head scratches. Then he says, “The hell are you talking about, bro?”

“Where’s the best place to buy groceries around here? I go to Dags, but they’re a little pricey.”

“We’re having a conversation,” he says, taking a swig from the Hennessy bottle, then staring at it in shock when he realizes it’s empty.

“Didn’t look like much of a conversation to me, but I saw how keen you were to chat, so I figured I would hop in. What’s the last good movie you saw?”

The barrage of questions does exactly what it’s meant to do—it confuses him and annoys him, but it’s not aggressive enough to make him angry.

The doors open at Broadway-Lafayette and I give the woman a little nudge. She waits a second and dives off the train. As she’s doing that, I get up, too, putting myself between Smiley and the door so he can’t follow.

The doors close and he pushes me. Not hard, but I move with it to create a little distance between us, so I can watch his hands. Guy who gets his face slashed like that probably carries a blade of his own to assuage the memory. It’s a safe assumption to make—I don’t lose anything by being wrong, but I gain a lot if I’m right.

Such as: not being stabbed.

“You know who I am?” he asks.

“I don’t,” I tell him. “My name is Mark. What’s your favorite color?”

“Red,” he says. “As in, what I’m gonna see in a second if you don’t back down.”

“You’re right, we don’t want that,” I tell him, struggling with all my might to hold at bay the shit-eating smirk that’s begging to crawl across my lips.

He goes for another drag on the bottle—still empty—considering his options. The train slows as it pulls into Second Avenue. I’m starting to wonder if this was a mistake. I don’t regret drawing his attention to me, but I could have played a softer hand. As the doors slide open, he mutters, “Asshole,” and stalks off.

Once the doors are safely closed, a few people clap. I give a little nod to the crowd, pleased at myself for keeping my cool, a little annoyed that no one stepped in before me. But most of all, wrestling into submission that toxically masculine urge that made me want to follow Smiley off and ask him: You know who I am?

—

Snowflakes whisper against the diner window. Not enough to stick, but enough to count as the first proper snowfall of the season. On the other side of Delancey, visible through a steady stream of traffic, is a small barren tree strung up with colorful twinkle lights. It looks sad, out there all alone like that, struggling to cast light in a dark and indifferent city, but that could just be a reflection.

Kenji brings my attention back to the countertop by tapping my notebook, which I helpfully took out and, unhelpfully, didn’t bother to open. His long gray hair is pulled back into a topknot, and, as always, he has a bemused smile on his face, like someone told a moderately funny joke. Not enough for a laugh, but enough to earn his respect.

“How is your eighth step coming?” he asks.

I take a sip of my coffee-flavored water and shrug. “It’s almost Christmas. Are we exchanging gifts? Because if you got me something, I don’t want to be empty-handed and feel like a dumbass.”

“Mark?”

“I’m a medium T-shirt. I have plenty of kitchen stuff. I don’t need more kitchen stuff.”

“Maaark?” Kenji says, drawing my name out in a low baritone, like he’s lecturing a small child.

“It’s coming,” I tell him.

Kenji chuckles as he leans back on his stool, looking around to make sure no one is in earshot. Besides an old man sitting in a booth at the far end of the diner, disappearing into a moldy brown suit as he does the New York Times crossword, it’s just us and the owner, Lulu. Her diner is a narrow little railroad-style joint, full of chrome, faux wood, and dust. The food is fine, but the privacy is top-shelf.

“What’s wrong?” he asks. “You’re distracted.”

I tell him about Smiley. About how I should be proud that I de-escalated the situation, even though I wanted to pound on his skull until shards of bone sliced into my knuckles.

“If you’re looking for affirmation, here it is.” Kenji pats me on the shoulder. “I’m proud of you.”

“Thanks, Dad.”

“I know I keep saying it, but that’s because it’s easy to forget,” Kenji says. “Choosing to change is not something you do once. It’s something you have to wake up every day and choose to do again…”

Kenji stops when Lulu appears in front of us. Her red hair is going white, steely green eyes shining through crimson cat-eye glasses. She hefts a glass carafe of coffee and tops us both off without offering any kind of acknowledgment before shuffling back to the register, where she busies herself with paperwork.

“It’s not easy,” Kenji says, his voice a little lower now. With his right hand, he strokes the intricate, colorful tattoo that dominates his left forearm—the tail of a dragon, the body of which wraps around Kenji’s torso. The dragon’s head takes up the entirety of his back. He tends to touch the tattoo when he’s remembering his previous life.

“The idea of actually sitting down with people…” I take a tentative sip of coffee, hoping the hot liquid will loosen up the thickening in my throat.

“Remember what I told you, all those years ago?” Kenji asks, spinning his mug on its plate.

“Willingness,” I tell him.

“I did an amends two nights ago,” he says. “I tracked down an old girlfriend who is living here, in Passaic.” He puts down the mug and folds his hand. “She runs a restaurant. Japanese-Mexican fusion. Whatever that is.”

“She didn’t comp you a meal?”

“I went at closing,” he says.

“And you just told her what you did?”

Kenji nods. “She seemed upset at first, a little scared, but she heard me out. When I was done, she said she didn’t forgive me, but it had been so long she no longer held a grudge. She told me she set down that pain a long time ago, and it was now mine to carry. She asked me to leave and never come back.”

“How did that feel?” I ask.

“In the moment, uncomfortable,” he says. “But I felt lighter on the walk back to the train. It had to be done.” He takes a long swig of coffee. “The more you do it, the easier it gets.”

I laugh a little at that. The idea of any of this being easy sounds ridiculous.

The thing is, I’m lying to Kenji. My eighth step—the list of people I should make amends to—has been done for a while now.

But the ninth step is actually making those amends.

And moving on to that means admitting these things to be true.

“Here’s the thing I don’t get,” I tell him. “The ninth step says we have to make direct amends wherever possible, unless to do so would cause further harm or injury. If that’s the case, we can do a living amends. Just, you know, live a better life. One of service. Why isn’t this whole program about living amends? How does it not cause further harm or injury to drop this kind of stuff in people’s laps? We’re just ripping off scabs. Putting them in a position of…What if they want payback?”

Kenji, with that smile again. “Spoken like every single person who doesn’t want to start their ninth step.”

My hands are flat on the counter, like I’m trying to hold myself down from floating away. These hands that have caused so much hurt, that have made my eighth-step list so goddamn long. Kenji seems to sense the shifting gravity and places his right hand over my left, to keep me grounded. My instinct is to pull away, but I appreciate the intimacy of it.

Especially because his hands have done the same kinds of things as mine.

“You’re my fourth sponsee,” he says. “Two gave up. One, his past caught up with him. You moved through the steps with real focus. You showed up for them. Then you got here and you hit a wall. I don’t want to lose another one. Remember, this is a kindness. Not just for the people on your list, but for yourself. What you are doing is learning to forgive yourself.”

“I know,” I tell him. “I’m just being difficult.”

“Very.”

Four in, hold for four, out for four, empty lungs for four.

He’s right. Moving into the ninth step means I can finish it, and then one day—well, I don’t expect to truly forgive myself, or to find some kind of inner peace, but maybe I’ll be able to sleep at night, or just hate myself a little less.

Maybe those things could be enough.

The door chimes behind us. A young couple comes in, holding up a phone at eye level, which they’re both smiling into like lunatics. He’s wearing a black skullcap and has a tattered scarf looped tastefully around his neck. She’s got big thick glasses, a fuzzy pink coat, and a shaved head.

“On today’s episode of Undiscovered Eats ,” the young man says, “we check out Lulu’s Diner, which is so off the beaten path it doesn’t even have a Yelp page, and—”

Lulu snaps her fingers, which stops him from talking, and without lifting her pen from paper, or her eyes from what she’s doing, she points to the door and says, “Get out.”

The two of them hover in the open doorway, the frigid December air chasing away the warmth. Neither of them knows what to say, and they look to us like we’re going to help.

I offer them a half shrug. “I wouldn’t mess with her.”

Without another word, they leave.

And that’s why we come to Lulu’s.

I realize Kenji’s hand is still on mine. We look down at where we’re touching, then back up to each other, and we burst out laughing. It was the pressure release valve that both of us needed in that moment.

Kenji reaches for his wallet. But I’m ready, a fifty-dollar bill folded in my pocket and ready to go. I slap it on the countertop and he sighs.

“Please…” he says.

“It’s all good, bud,” I tell him.

Kenji is big on custom and tradition and doesn’t like that I always pay. But I walked away from my old life with a sizable nest egg. He walked away with the clothes on his back.

“Thank you,” Kenji says, offering a slight bow. “And yes, it would be nice to exchange presents this year. It’s been a long time.”

“Oh, that was just me being difficult. Again. After last Christmas…”

“Perhaps,” he says, “we should take a bad memory and replace it with a good one?”

I’m struck by a couple of feelings at once: giddiness at the idea of doing something so normal as exchanging gifts, and then, of course, the noxious shame of what happened the last time I wrapped a Christmas gift.

But it feels like another small step on the path leading to the kind of life I want to build.

The kind where normal things happen.

“Spending limit is fifty bucks,” I tell him. “Sound good?”

“Sounds good.”

We get up and shrug into our coats. Lulu may notice, or she may not. I yell across the diner to her. “Hey, Lu, it’s almost Christmas. You ought to put up some decorations.”

“Hmm,” she says, I think.

Kenji gestures toward the door. “We still have to get the donuts.”

—

The church basement is sparse, but large enough to fit a few dozen people for a mixer or a fund-raiser. The coffeepot is gurgling next to an open box of donuts on the folding table in the corner. The walls are robin’s-egg blue and the floor is a black-and-white-checkered pattern. It looks frozen in time, and that time is 1982.

Kenji leans forward, placing down a silver lipstick-sized device on the small table in front of him, which will prevent us from being heard or recorded outside this room. Next to that, his copy of the Big Book, even more tattered than mine. His is held together with a thick blue rubber band so the pages don’t spill out.

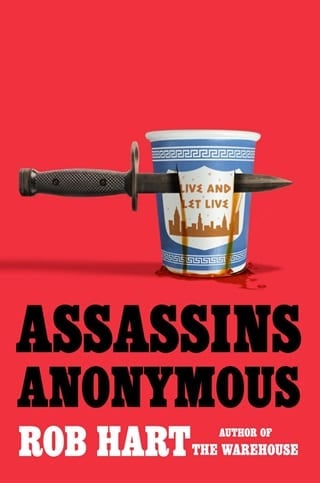

“Welcome to Assassins Anonymous,” he says. “My name is Kenji, and I am a killer.”

Kenji looks around the room, regarding each one of us in turn. There are five of us in total, seated on brown metal folding chairs under the buzzing fluorescent lights.

Valencia is wearing a red flannel and jeans. Her jet-black hair is cut short and tousled like she just got out of bed. She has the same look she always has on her face: like she smells something terrible.

Booker is every inch the jarhead—bald, black tribal tattoos decorating his russet skin, combat boots, and fatigue pants. Eyes darting back and forth, waiting for something to happen so he has an excuse to explode.

Stuart is the youngest of the bunch by at least a decade, and dresses even younger than that—swimming in an oversize black sweatshirt and baggy cargo pants. He perches on his seat like an animal who steals food from larger predators.

“Assassins Anonymous,” Kenji says, “is a fellowship of men and women who share their experience, strength, and hope with each other, that they may solve their common problem and help each other to recover. The only requirement for membership is a desire to stop. We are not allied with any sect, denomination, politics, organization, or institution; our primary purpose is to stop killing and to help others achieve the same.

“We do not bring weapons into Assassins Anonymous, nor prior political affiliations. If any of us were known by any particular handle or nickname, we do not use it here. We share our stories, but we obscure details as best we can. If any of us seek to bring in new fellows, we agree to have them properly vetted. This is to protect us, not just from prying ears, but from each other.”

He’s not kidding. The story goes, there was a meeting in Los Angeles a few years ago where two professional hitman revealed their stage names and inadvertently discovered they’d spent decades locked in a game of cat and mouse. By the time the meeting was over, four people were dead.

Anonymity is an important component of any recovery process, and it’s especially important here.

“Valencia,” Kenji says, “could you read the steps?”

Valencia shifts in her seat and closes her eyes, taking a moment to recall the words. In a regular AA meeting, there would be a handout you could read from; here, we prefer not to put things in writing.

“We really gotta do this every time?” Booker asks.

Kenji isn’t chuffed. That’s just Booker. “Remember,” Kenji says, “we have steps to keep us from killing ourselves, and traditions to keep us from killing each other. Valencia?”

Booker exhales sharply, taking the wooden rosary beads from around his neck and wrapping them around his left hand, like he does at the start of every meeting. I want to point out the irony of that, but now is not the time. Valencia begins:

“One, we admitted we were powerless—that our lives had become unmanageable.

“Two, we came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

“Three, we made a decision to turn our will over to the care of a higher power, as we understood it.

“Four, we made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

“Five, we admitted to our higher power, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

“Six, we were ready to have our higher power remove all these defects of character.

“Seven, we humbly asked it to remove our shortcomings.

“Eight, we made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

“Nine, we made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

“Ten, we continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

“Eleven, we sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with our higher power as we understood it, praying only for knowledge of its will for us and the power to carry that out.

“Twelve, having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to others like us, and to practice these principles in all our affairs.”

Hearing the steps has the same effect it always has on me: a desire and excitement to complete them, and an abject terror at the proposition.

Valencia continues: “No one among us has been able to maintain anything like perfect adherence to these principles. We are not saints…”

This line always draws a couple of chuckles.

“The point is that we are willing to grow along spiritual lines,” she says.

Valencia looks up at Kenji, who nods.

“Thank you,” Kenji says. “Now…”

Stuart’s hand shoots up at teacher’s-pet speed.

“Stuart,” Kenji says, glancing at me, “we have some other business…”

“Nah,” I tell him. “It’s all good. We’re not in a rush here.”

Stuart twists his hands in his lap. “Yeah, so I…”

“This shit again,” Booker mutters, looking at the rest of us like: C’mon, right?

Stuart immediately shuts his mouth, and his eyes drop to the floor.

“Booker, you know that’s not how we do things,” Kenji says, calmly but sternly. “Everyone is allowed space to share, without judgment. The only requirement is that you have the desire to stop.”

“It’s just,” Booker says, waving a scarred hand in Stuart’s direction, “he’s a freak, right? We’re all thinking it. I don’t like that he’s sitting here with us. What we did, we did to people in the game. I killed warlords and terrorists. Not innocent people.” He looks at Stuart. “How the hell did you find out about this, anyway? It’s called Assassins Anonymous. Not Serial Killers Anonymous.”

Kenji looks at me, hoping I’ll jump in. Another difference from a normal AA meeting, where people are given the runway to speak—our meetings often mutate into talk therapy sessions.

“Mark?” Kenji asks.

Booker’s attention snaps to me.

Stuart gives a tentative glance in my direction.

“Couple of things here, B,” I tell him. “You know as well as I do that he got vetted by Kenji, just like everyone else. Second, we take in hit men, and hit men ain’t assassins. You’re entitled to your feelings, but we’ve had this conversation more than once. What we did, we did for money, or the thrill, or because it’s the only thing any of us is good at. Stuart over here”—I gesture toward the cowering figure—“he’s got a real compulsion. The kind of behavior you would more traditionally associate with an addiction. Which means this is the best place for him. Him being here means someone is alive. You want to do carveouts for mercenaries, too? ’Cause that wouldn’t work out so well for Marines who switched over to private contracting…”

Booker involuntarily flexes the muscles in his forearms. I’ve gleaned that much about him from his shares, and he doesn’t like that I have him pegged down to his branch. Marines are the easiest to spot, though; it’s the bravado.

“…but we’re all here trying to be better,” I tell him. “So I think we should support Stuart, not tear him down.”

“Whatever,” Booker mutters, folding his arms.

I look at Valencia. The one I’ve had the hardest time figuring out, because she tends to speak the least. Booker is a Marine turned mercenary; Kenji was a Yakuza hitter. Stuart is Stuart. All I can tell about Valencia is she’s Mexican, but she doesn’t carry herself like military or police, so I figure she had something to do with the cartels.

“V, what do you think?” I ask.

“I think this is a little too much crosstalk,” she says, staring past the circle and through the wall.

“Back to the meeting.” I wink at Stuart. “What have you got for us, Stu?”

“Well,” he says, still looking at the ground, now hugging himself for support. “Last night, I went to this bar near my apartment, because I like their fries. Their burgers are sort of meh, but their fries are good. So I got a plate of fries, and the bartender, she was my type.” His lips curl into a smirk, and I think all of us freeze a little at the word type .

The more Stuart talks, the faster his voice gets: “It’s Astoria, so it’s generally a quiet neighborhood after last call. I could have followed her home, found out where she lived. Or I could have talked to her and learned a little about her. I was always good at that. Getting people to open up to me. But I didn’t. I finished my fries and I paid my bill and I went home.”

Kenji claps, enthusiastically, and the rest of us follow with a little less verve. “Good for you, Stuart,” he says. “How did that feel?”

Stuart tilts his head, digging the thumb of his left hand into the palm of his right. “I still wonder what her head would look like sitting in my fridge with an apple crammed in her mouth, but the important thing is, it’s still on her shoulders, right?”

I can feel the discomfort snaking through the room, so I clap again. No one follows, but it doesn’t matter. The silence is broken. “One day at a time, buddy,” I tell him. “One day at a time.”

Booker mutters something, but I can’t make it out.

Kenji sighs and says, “Thank you, Stuart. Now, our next meeting is going to be a special one…”

A flush of warmth spreads through my body. Doesn’t matter how far we make it in life, we’re all just little kids who want a gold star from their teacher.

“Mark is a few days out from one year,” Kenji says.

At this, everyone claps, much more enthusiastically than they did for Stuart.

Kenji has seniority here: five years and change. Valencia has four, and Booker is over three. Stuart, the new addition to the group, is still a few months in, which is a delicate time for people in recovery, and why I want to encourage him.

Everyone waits, offering me the space to speak.

“I almost can’t believe it.” I take my last prize—my six-month chip—out of my pocket. The inscription is barely legible, the hard plastic surface worn smooth from how often I need to rub it between my fingers and remind myself it’s real. “I was thinking about it today, how that feeling never goes away. The muscle memory. And it made me think, can I really change? But I guess it doesn’t matter whether I can or not, the only important thing is that I want to.”

I look up and meet everyone’s eyes in turn.

“I just want to say, I’m thankful for all of you. No one understands what taking a life does. How it screws you up, but then how even more screwed up it is that you get used to it, and then it just becomes a job. Then you go see a movie and it’s like this noble profession, but the reality is we’re just tools, so somebody with power can have even more power. I can say, with complete and total honesty, even though I still struggle with my programming, I don’t miss killing. And that feels good. From the bottom of my heart, I’m thankful for you scumbags.”

That draws a big, explosive laugh from Booker and a judgmental look from Kenji. Before he can say anything I put my hand up.

“I don’t say scumbags because you’re former killers. I say it because you always leave me alone to clean up after the meetings.”

“Okay,” Kenji says, with just the slightest roll of his eyes. “We’ve got some time left. Booker, would you like to share?”

They do, and the story remains mostly the same. Booker talks about the ghosts of past victims, the ones who follow him through the grocery store and stand by the foot of his bed at night. Valencia talks about wanting to be a mom, but not wanting to be a mom who kills people, and how one day she hopes to be worthy of the privilege. Kenji talks about the amends he made the other night, to the girlfriend of a man he killed in Kyoto.

There are no time limits. With only five of us, it can sometimes be hard to fill an hour. All it takes is for someone to be in a mood. But even on the nights we end up telling the same stories, I find comfort in being here. In seeing these people and knowing I’m not alone.

As I listen to them I consider the upcoming milestone.

One year since the biggest mistake I ever made, if you’re not counting all the others.

Contentment courses through me, and at the end of the hour, when it’s time to say the serenity prayer, I fold my hands together and speak in unison with the group, and it’s like I’m saying it for the first time:

“Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

—

With the room cleared, I close my eyes and take a deep breath. I like to bust on everyone for leaving me to clean, but really I enjoy it. It’s meditative, allowing me space to process the events of the meeting. A nice little decompress before I head back into the world, where the lights and the sounds and the people put me back on edge.

For a few moments I feel safe.

There’s a shuffle behind me. I turn to find Stuart, standing awkwardly on the other end of the room. His hands are clasped in front of him and the way he’s looking at me, eyes unblinking, makes me think of a bug, like I turned on the light and caught him and he could bolt in any direction. Maybe I’m just uneasy because I know what he used to get up to in his free time. The silence between us stretches for a beat too long, so I ask, “How you doing there, bud?”

“What is the difference between hit men and assassins?” he asks.

“A hitman gets paid by a political or criminal organization to kill someone. An assassin kills for religious or political purposes, but they don’t always get paid. The lines are blurry. Lee Harvey Oswald was an assassin, but there are guys and gals in this fellowship who changed the course of world events and you’d never know, and they got paid very well to do it. The terms are sort of interchangeable but sort of not. Kind of like how all bourbons are whiskeys, but not all whiskeys are bourbons?”

Stuart shakes his head. “I don’t get it.”

“Yeah, I pushed that one too far. It’s the best I got at the moment, though.”

“What does that make me, then?” he asks.

“A killer, same as me,” I tell him. “Someone who belongs here, same as me.”

Stuart takes a few steps forward, and I tense, and I think he sees it because he stops. One thing I’ve learned about him, and a thing I actually give him credit for, is that he’s aware of the effect he has on people. “I wanted to say I’m sorry for interrupting Kenji’s announcement,” he says. “And thank you, for the thing with Booker.”

“Booker sleeps in a bed made of sandpaper. At the end of the day he’s not a bad guy. None of us are. We just have the luxury of recognizing that we’ve made mistakes.”

“I like that,” Stuart says, chewing on it. “The luxury.”

“Don’t give me too much credit. Kenji said it to me once.”

Stuart looks down at the floor. “I get it, though. I’m not like the rest of you. Not really.”

“Hey, Stu.” I turn to him fully and wait for him to bring his eyes to mine. “It’s good that you’re here.”

“Thank you,” he says. “That means a lot, coming from you. Listen…” He looks down at the floor again, shuffling his feet, before looking back up at me. “I don’t have a sponsor yet. Would you consider…doing that?”

A clammy wave passes over my skin as it erupts into goose bumps.

You don’t have to have a sponsor in recovery. Kenji sponsors me, but he doesn’t have one. Booker and Valencia sponsor each other. I never considered taking on a sponsee. Up until now I’ve been happy to defend Stuart—because if he can change, so can I—but taking an active role in his recovery is a different level of commitment. And not one I’m ready for. I’m still trying to handle my own.

“I need to think about that,” I tell him. He nods, and then, without saying anything else, he steps through the darkened doorway at the far end of the room. With him gone, the air feels a little less thick.

A stew of complicated emotions mix in my gut. A little regret, that I might have hurt his feelings. A little relief, that I may have shut the conversation down.

Back in the day, I would have done the math, and the equation would be elementary—ending Stuart’s life would have the potential to save so many others. Then I would slit his throat and leave him bleeding in a ditch.

I’m a different person now. Ultimately I do want him to succeed, but the sponsor/sponsee relationship is an intimate one.

I’m going to have to talk to Kenji about this. He might not think I’m ready.

One can hope.

As I’m about to dump the leftover donuts in the trash can next to the table, there’s a squeak of a footstep behind me.

“What’s up, Stu, forget something?” I ask.

As I turn, a boot smashes into my chest.

Fullepub

Fullepub