4

4

December 27, 1880

Thursday

D 'A GOSTA RESTED IN A wing chair, watching the rising sunlight try in vain to penetrate the shutters that wreathed the parlor in gloom.

In the hours since the assault, the house had settled into a frozen state of shock. Féline, the woman slashed by Munck upstairs, had been sutured and dressed by Pendergast and given an injection of antibiotics he'd brought from the twenty-first century. Murphy, the coachman, had taken the dead man—the children's tutor—to the basement and securely interred the body beneath a newly laid brick floor. Joe, Constance's brother, was upstairs being looked after by a maid. The rest of the servants had retreated to their rooms save for Gosnold, the butler, who insisted on remaining at his position in the parlor.

The urn and spilled ashes had been swept up and taken away. The card that had come with it, however, remained where Pendergast had placed it after reading the contents: on a side table near D'Agosta. All the rest of the night, D'Agosta had been unable to bring himself to read it. But as the light outside continued to brighten, he finally turned his head painfully toward the table, reached out, and took it up.

My dearest Constance,

I present, with condolences, the ashes of your older sister. They come with my thanks. The surgery was most successful.

Your plan was a desperate one from the start. I sensed you would double-cross me; it was just the mechanics of your betrayal that puzzled me. And then, mirabile dictu, the instrument that could lay bare the precise scheme was delivered to Bellevue… and from there into my hands.

You have the Arcanum; I have you: or rather, your younger self. Give me the formula, true and complete, and the girl will be returned to you intact. And then our business will be concluded… save for one thing. This is not your world to meddle in; it is mine. You, and those who followed you, will return to your own forthwith—or suffer the consequences.

You will signal your agreement by placing a candle inside a blue lantern and hanging it in the southeastern window of the third floor. I will then contact you with further instructions.

If I do not receive this signal within forty-eight hours, young Constance will suffer the fate of her older sister.

Until our next correspondence, I remain,

Your devoted, etc.

Dr. Enoch Leng

D'Agosta cursed under his breath and laid the note aside.

In the moments after the urn arrived, Constance had been incandescent with rage and—D'Agosta was certain—at the very brink of madness. Her feral hysteria had been the most unsettling thing he'd ever witnessed. Pendergast had said nothing, his face an expressionless mask of pale marble. He had listened to her imprecations and recriminations without response. And then he had risen, taken care of Féline, and silently supervised the cleanup of the murder scene and disposal of the body. Everyone appeared to be in unspoken agreement not to involve the authorities—which, D'Agosta knew, would only lead to disaster. And now the three of them remained silently in the parlor, sunk in a mixture of grief, guilt, and shock as a new and uncertain day crept into life outside the shuttered windows.

After her tirade, Constance had abruptly fallen silent—and remained that way. Now she disappeared upstairs. Ten minutes later she reappeared, holding a small, well-worn leather notebook.

She turned to the butler, who was still waiting in the parlor entrance. "Light a taper in a blue lantern and place it in the window of the last bedroom on the right, third floor."

"Yes, Your Grace." Gosnold turned and disappeared.

"Just a moment," said Pendergast, looking at Constance. "Is that the actual formula for life extension—the Arcanum?"

"Did you think you were the only one who had a copy? You forget: I was there while he developed it."

"So you intend to comply with Leng's instructions? You'll give him the Arcanum—and thus allow him to carry out his plan?"

"It won't matter that he has the Arcanum. Because he won't live long enough to use it—I will see to that."

Pendergast shifted in his chair. "Don't you think Leng has already anticipated this intention of yours?"

Constance stared at him. "It won't matter."

"I'm afraid it will. Leng knows everything. He anticipates everything. Whether you care to admit it or not, he is cleverer than either of us. Not only that—he now knows I'm here. He knows why we're here. He'll be prepared for whatever you do—whatever we do."

"He will not," said a soft voice from the darkness, "be prepared for me ."

A match flared in a rear doorway of the parlor.

And then a figure stepped forward, lighting a salmon-colored Lorillard cigarette set into an ebony holder. The flare illuminated the pale face, the aquiline nose and high smooth forehead, the ginger-colored beard, and the two eyes—one hazel, the other a milky blue—of Diogenes Pendergast.

D'Agosta felt numb with shock. Nobody spoke. Diogenes Pendergast could not be here, he thought—not in this parallel universe, not in 1880. But here he was.

When no one spoke, Diogenes took off his coat and tossed it over the back of a chair, sat down, then carefully placed his hat on the nearby table. "I'm sorry, Frater . It's rude of me to intrude like this. I would have knocked, but—not wishing to disturb—it seemed best to let myself in. This is a dispiriting state of affairs," he went on, in a voice like melted butter poured over honey. "And you're correct when you say our dear ancestor will be prepared for whatever you all might do. But that's precisely what makes my presence so fortuitous."

"How did you get here?" Pendergast asked in a tight voice.

The end of the cigarette glowed red as Diogenes inhaled, and the scent of cloves began to spread across the parlor. "The garden gate was left open, so to speak. Back at Riverside Drive, where that uncouth scientist used your machine in an effort to enrich himself. Which machine, by the way, is now unfortunately no longer operational."

Not operational? This observation, despite the nonchalance with which it was delivered, sent a stab of anxiety through D'Agosta.

Diogenes paused to take a drag from the cigarette and issue a stream of smoke. "It's rather barbarous, this world without electricity," he said in the same languorous accent he'd affected since first appearing. "But at least they haven't yet discovered lung cancer."

"Why," said Constance, in a voice cold enough to freeze nitrogen, "should we ever think of associating ourselves with you again?"

"My dear Constance, let me ask you a question," Diogenes replied. "What is it I do best?"

Constance did not hesitate. "Killing."

Diogenes patted his gloved hands. "Exactly! A killer of hopes, of dreams, of love—but most especially of human beings." He stabbed out the half-smoked cigarette in a nearby ashtray—as if to punctuate this pronouncement—then drew out another and fitted it to the holder. "And now—" he turned to Pendergast— "a question for you: do you recall the last thing I said, that night I disappeared into the swamps of the Florida Keys?"

Pendergast hesitated just a moment, then quoted: "I am become death."

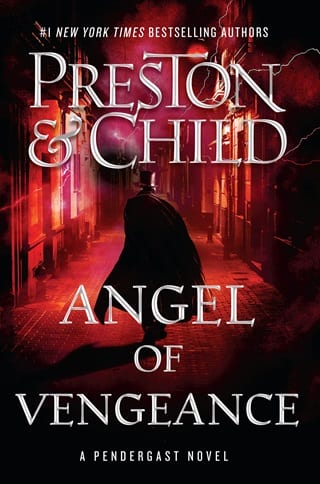

"Excellent. My words exactly. I'm so glad to finally be in the position of doing a favor for those I love. A singular favor." He lit another match. "I am come," he said, applying the match to the fresh cigarette, "as your Angel of Vengeance." Then the match was shaken out and he chuckled: a low and ominous sound that, though brief, seemed to linger forever before dying away, leaving the room once again in shadow and silence.

Fullepub

Fullepub