Chapter One

“Nearly home, sir!” the coachman said, grinning and tipping his hat. As if it were good news.

Henry Willenshire forced a tight-lipped smile and climbed back into the carriage. They’d changed horses for the last time and would reach his family home all too soon.

If a wish could have carried him back to France, he would have done it in a heartbeat. As it was, his absence had earned him frowns and faintly veiled disapproving remarks from his family.

The four Willenshire siblings were in a rather… unique position. The eldest boy, William, had of course just inherited their father’s title of the Duke of Dunleigh, and they had all naturally assumed that, on their father’s death, they would inherit parts of the tremendous Willenshire fortune, too.

Not so. There were conditions to their inheritance.

Henry clenched his teeth. Every word of that will, his father’s will, was burned into his brain.

“ In case my family should forget what is due of the Willenshires and the great Dunleigh Estate, I have chosen to remind them. While I cannot stop my eldest son inheriting his title and the small amount of money attached to the estate, the rest of the property and money is mine to dispose of as I wish. The inheritance due to my widow will remain unchanged and unencumbered. However, before my children may access their inheritance, they are required to marry in a court of law. On the date of their marriage, they may receive their full inheritance…”

It was unprecedented, as far as Henry knew, a man of the late Duke’s standing leaving a stipulation in his will to force all of his children to marry to receive their rightful inheritance. And there was a deadline, too. They had twelve months from the date of the will’s reading to marry or lose their money forever. Henry remembered vividly how he’d felt, how numb and surreal it had all seemed, like it was a bad dream that he would wake up from at any moment.

Of course, none of them were pleased about the will. A further stipulation had left Katherine, Henry’s only sister, obliged to marry first, or else none of the boys could receive their money. Another unfairness on the late duke’s part. One of many.

Henry let his head tilt back against the carriage seat. He’d considered taking up apartments in town, rather than facing his family, but really it cost too much. Still, he wasn’t ready to relinquish his freedom altogether, so perhaps he would have to find the money from somewhere. It wasn’t as if he could borrow it. William, the new duke, had not received his inheritance yet. With the exception of Katherine, none of them were married.

She’s lucky, Henry thought glumly, conjuring up images of his sister’s smiling face on her wedding day. Timothy Rutherford was an old family friend, and the two loved each other. Even Henry could see that.

With a lurch, the carriage came to a halt, some time after the last stop. Henry could not have said how long, only that he very much did not want to go home.

The place doesn’t even feel like home.

Rain was falling lightly, slowly soaking the gardens of Dunleigh House. It was an ugly place, in Henry’s opinion, especially when compared to the beautiful, sun-drenched stones of Spain, Italy, and France.

Don’t think about it, he told himself, grimly climbing out of the carriage and leaving the coachman to take down his bags and boxes. You’re not there. You’re here. For now, at least.

“Ah, the prodigal returns. I was sure you’d find more business to keep you abroad.”

Henry darted up the stone steps, ignoring his brother.

William Willenshire, the new Duke of Dunleigh, was leaning against the doorway, arms tightly folded and lips pressed into a thin and disapproving line. Henry shook off the lingering dampness from his hair, like a dog.

“Hello, Will. No, ‘welcome home, Henry’?”

William rolled his eyes. “Welcome home, Henry. But let’s not pretend that you want to be here.”

Henry said nothing. He had been pursuing something to do with wine, which could have kept him in France for months yet, but it had all fallen through, unfortunately. But all was not lost. There was a self-made gentleman, Mr. Charles Fairfax, who might make a decent business partner. Henry had made his acquaintance recently and they had promised to meet up again in England. Anything to distract him from the fact he had to marry or live destitute.

“Some messages arrived for you today,” William said abruptly. “Lord Percy Fletcher wants to see you, your old friend.”

“How nice. I haven’t seen Percy for a while. Is my old room ready?”

“I’d like a quick word with you, first,” William said shortly, turning on his heel and walking along the corridor. He didn’t wait to see if Henry followed him.

Henry bit his lip, considering how funny it would be to ignore William’s summons and just go on up to his room.

Sighing, he followed his brother.

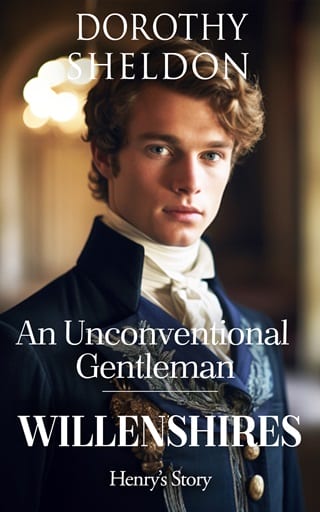

They passed through a cavernous hallway, ceilings swooping high and forbidding above them. A vast family portrait glowered down at passersby underneath. The family resemblance was clear, glittering hazel green eyes staring blankly, chestnut locks gathered in neat, sedate arrangements around faces and necks. Henry saw himself there and tried not to look. He’d been younger then, already longing for the freedom of travel and escape. His dark hair was massed around his head, his eyes darkened by the painter. Beside the pale, oval faces of his older brother and Katherine, he looked plain and ill-tempered.

Alexander, the youngest of them all, was the only one who was smiling.

“Where’s Alexander?” Henry asked impulsively, lifting his voice to carry over the clack-clack of their boots on the marble floor. “I thought he’d be here to welcome me.”

Was it his imagination or did William’s shoulders tense.

“I couldn’t say where Alexander is. He went out last night and hasn’t come home.”

Not the response Henry had hoped for. They were quiet for the last few minutes, taking a sharp turn into the study.

A tea tray was set out already, and the fire was lit.

“This is nice,” Henry commented.

William sat stiffly down on the chair behind his desk, gesturing for Henry to take the chair opposite .

“Two months is a long time,” he said bluntly. “You shouldn’t have left, Henry. Certainly not so quickly after Katherine’s wedding.”

Henry bit the inside of his cheek. “She’s happy enough, isn’t she? Why do I need to stay?”

“Why do you need to stay? Why do you think? We have ten months left on Father’s wretched deadline. Katherine has her inheritance, but I’d quite like mine, too.”

“And what, exactly, does this have to do with me?”

William pressed his lips tight together again, obviously controlling his temper. Henry lounged coolly in the chair, hooking one leg over the arm. He wasn’t going to help him out. None of his siblings knew what it felt like to live in a cage.

Well, perhaps that wasn’t fair. But William and Alexander had always planned to marry one day, and Katherine would have to marry, on account of being a woman and all. Unfair and annoying, but there it was.

However, Henry was the second son, with few prospects and few expectations placed on him, and he’d hoped for a life of freedom. Love and marriage might well come along, but if it didn’t, why would it matter? It wasn’t as if he was going to be the Duke or wanted to be.

“If I choose to renounce my inheritance,” Henry continued, once the silence had become uncomfortable, “whose fault is it of mine? I can make my own way in the world.”

“Really? Because none of your enterprises have flourished so far. I hear that your wine business was a disaster. I have no intention of bankrolling your lifestyle.”

Henry flushed. “I have another promising scheme coming up.”

“You always have another promising scheme. But, no, as you say, it is none of my business if you choose to renounce your inheritance. You and I have never been friends, Henry, but I thought you might have stayed for your siblings.”

“Katherine can take care of herself. Her letters seem very happy, and I think she’s pleased with the match she’s made.”

“She is, but I’m not talking about her,” William leaned forward, resting his elbows on the desk. “Alexander is not going well. ”

Henry bit his lower lip hard, tasting copper.

The stipulations and deadlines of their father’s will clearly bothered Alexander. He was an anxious young man at the best of times and had recently taken to dealing with his stress by excessive drinking, occasional gambling, and keeping remarkably poor company. When Henry had left, Alexander had begun to look pale and ill.

A flash of guilt surged through him. Henry swallowed it down as best he could.

“Well, I’m home now,” he said, lightly. William did not smile.

“It remains to be seen whether you’ll be of any use.”

The remark stung, but Henry was careful not to let it show on his face. He grinned instead.

“Careful, Will. You’re starting to sound just like our dear Father.”

William went white and then red in quick succession. There was no telling where the conversation might have gone if the study door hadn’t flung open, admitting Lady Mary Willenshire, the Dowager Duchess of Dunleigh.

“Henry, my darling boy!” the Duchess exclaimed, arms held wide. “I had no idea you’d returned so early. Come kiss your mother.”

Henry got dutifully to his feet, embracing his mother and kissing her powdery cheek.

“You look very well, Henry, although you have caught the sun a little. How was France? Deadly dull, I imagine.”

“France is never dull, Mother,” Henry responded, smiling.

“Are you glad to be home?”

He only hesitated for a heartbeat.

“Of course I am, Mother.”

“Good, good. Ah, the tea tray is here. I’ll pour.”

While the Duchess busied herself pouring out three cups of tea, Henry and William tried to avoid staring each other down.

Henry was aware that his siblings were somewhat unforgiving towards the Duchess. She was a faded woman who had once been a great beauty and had long since had any spirit or character crushed out of her beneath the late Duke’s unforgiving heel. Their father had worked hard to mold his children into the shapes he wanted – forcibly, if necessary – and had already achieved his goal with his wife.

Naturally, then, he had no further interest in her. The Duchess, however, still wore mourning for him, and would likely stay a widow for the rest of her life, clinging to an idealized memory of a terrible man.

Henry thought that his siblings – William, in particular – should be a little more considerate.

“Two months is entirely too long,” the Duchess was saying out, handing a cup of tea to William. “You should have been here to support Katherine through those tricky early months of marriage. She is extremely stubborn, and would never listen to any of my advice.”

“I think Katherine’s marriage is doing very well, Mother,” William said tightly.

The Duchess cast Henry a look. “Well, Timothy is a nice enough man, but you know that he only writes… writes novels .”

She whispered the word, as if saying it loudly might summon a wicked heroine right there in their home.

Henry hid a smile. Timothy Rutherford, like him, was a second son, one whose father made no secret of how strongly he disapproved. Spurning his father’s money and influence, Timothy had moved into his own apartments and made a living writing novels under a pseudonym. They were good novels, too. Better than good. They’d rocked polite Society, and everybody had read at least one of Timothy’s works, even if they didn’t know that Timothy was the author.

The man was quiet and placid, had great integrity and a bottomless imagination. He had loved Katherine for some time, if Henry was not mistaken, and he privately thought that his sister could not have chosen a better man.

And, of course, her marriage had opened up the way for her brothers to receive their inheritance.

“Any further engagement on the horizon?” Henry enquired and earned himself a glower from William.

“No,” William said shortly.

His eyes flickered to the side, and Henry followed his gaze. A silver locket lay on the desk. It looked like a woman’s necklace, and Henry dredged up a memory of William finding it at a ball, belonging to some mystery woman whom nobody knew. No point in keeping it, in Henry’s opinion.

Which, of course, William would never ask for.

“How long are you staying, Henry, dear?” the Duchess asked, handing a steaming cup of tea to her second son.

“Indefinitely, if you’ll have me,” Henry said, deliberately meeting William’s eye. “Unless it’s inconvenient, of course.”

William sighed. “It’s never inconvenient having you here, Henry. This is your home, too.”

A knot loosed in Henry’s chest, one he hadn’t even known was there.

“I’m glad,” he murmured. “I’m not… not displeased to be home.”

William arched an eyebrow. “High praise, indeed.”

The Duchess glanced from face to face, oblivious to any undercurrent of tension between her sons.

Story of our life, Henry thought grimly. The Duchess had never seemed to notice her husband torturing their children. If she had noticed, she had done nothing about it, so it was more palatable to believe that she hadn’t noticed.

It was what Henry preferred to believe, at least.

“If you’ll excuse me,” Henry said politely, putting down his teacup, “I’ll retire to my room. I have a great deal to get done.”

“I’m sure,” William muttered. Henry considered demanding to know what that was meant to mean but decided against it.

Fullepub

Fullepub