Chapter 3

CHAPTER 3

E lizabeth Bennet stepped away from the easel to better appreciate the colors on the canvas through the east-facing windows of her father’s long-abandoned hunting lodge. Orange was a bold choice for her clouds, but if nature could get away with it as it had in last night’s sunset, then why should she not include the vivid color in her painting?

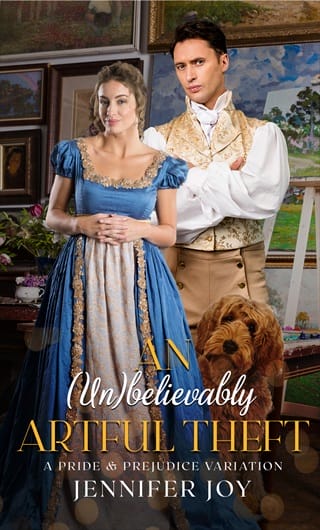

She dipped the bristles into the paint on her palette. “A dab of orange here, and a dab there,” she said, turning to her companion, who looked up at her with unadulterated adoration. “What do you think, Remy?”

Rembrandt wagged his tail happily, his tongue lolling out of his mouth. He was her most loyal devotee. Her only devotee. He barked and nudged her free hand with his wet nose. She ruffled his curly brown fur. Remy was a big oaf with more heart than intelligence, but he was her favorite art adviser, always approving. He darted to the door and looked back at her eagerly. Remy was also an excellent timekeeper.

“Already?” she asked begrudgingly. It felt like she had mixed her paints only five minutes ago. Reaching for the turpentine, she began cleaning her brushes near an open window. It was November-cold, but the smell was potent, and she could not risk it clinging to her.

After checking her hands to ensure that they were free of paint, she removed her apron and placed the easel against the wall, away from the light. Stacked against the wall were two other finished paintings. With a hard-earned sense of accomplishment, she looked at the trio of completed canvases leaning against the shaded walls. Her technique had improved with each landscape. Rolling hills, vivid skies, ribbons of streams… Her heart tugged at the familiar longing and her fingers twitched.

Landscapes were lovely, but her dream was to paint people. What she would give to paint the light in an eye, the curve of a lip, the unguarded expressions that revealed a person’s true character.

With a sigh, she picked up her sketchbook and flipped it open. Her father’s eyes glinted at her over the top of the spectacles perched partway down his nose. It was the look he gave Elizabeth when something caught his humor, which happened often. It made her smile.

On the next page, her mother, framed in decadent lace and holding a glass of ratafia, narrowed her gaze at someone off the page, most certainly an eligible gentleman she intended for one of her five unmarried daughters. As far as her mother was concerned, marriage was the solution to all their woes, both real and imagined.

Elizabeth’s eldest sister, Jane, personified kindness with her soft features. She was more light than shadow. Simply looking at her picture filled Elizabeth with calm.

Elizabeth was the second-born, and then came Mary. Mary might possess plainer features, but they transformed into a sparkling beauty when she smiled. Unfortunately, the self-righteous views of others easily influenced her, and those harsh opinions too often showed in her thin mouth and squinted eyes.

Kitty and Lydia took up the next page. Elizabeth had sketched their expressions as they giggled with their heads close together. Individually, each was as astute as any other young lady of her age, but combining their intelligence resulted in a deficit that did neither of them credit. Kitty was older and capable of sense, but she looked to Lydia, who was bolder and too selfish for reason. Lydia’s chin tilted up at a defiant angle, her bold gaze reflecting absolute confidence in her ability to get whatever she pleased.

Last was Elizabeth’s self-portrait. Except for the eyes―of which Elizabeth was admittedly proud―her face was dreadful. Her nose was too thin, her mouth too wide, her jaw too firm, her hair too wild. She did not have Jane’s symmetry. Still, it was a true rendering, like looking in a charcoal-shaded mirror.

Elizabeth had worked diligently to improve her artistic skill and took great satisfaction in her ability to reflect the subjects’ personalities―an attribute unnecessary for the landscapes she created.

Portraits earned much more money…

She sighed again and closed her sketchbook. Someday she would sign her own name at the bottom of her work. For now, she must be content to continue as Mario Rossi, an insignificant Italian painter with a common name and unknown origin. As a man, she could earn money. As a man, she could paint. But unless Elizabeth developed a convincing Italian accent and dressed the part of a male, she would never be able to paint live portraits… which meant she must continue to paint landscapes.

Remy’s tail slapped against her legs. He pranced toward the door, reminding her that it was time to return to Longbourn and join her family around the breakfast table. After grabbing the book she always carried along with her sketchbook, she closed the door behind her with Remy at her heels.

Her mind wandered back to her problem as they walked. At her current pace, she had been completing one painting a month. It was not much, but it was all she could accomplish in the precious minutes she snatched during the day.

After having sold her work for four years, her paintings had earned a respectable sum that, with the help of her uncles, she had invested and grown. It was not enough to save Longbourn, though. Not unless she made some changes .

Could she complete one painting every fortnight? That was half the time she presently required, but if she managed it, her income would double. Good lighting was her biggest obstacle during the late autumn and impending winter months as well as the unreliable weather. She loved to walk and read out of doors, but if she insisted on walking too often in the rain and wind, her family would suspect something was amiss.

She could work up an idea in her sketchbook the evening before. She would have to resist the urge to adjust the scene as the painting developed before her eyes and revealed its story to her, but if she settled on an image and placed it clearly in her mind, it would shorten the hours she spent painting. That would gain her some precious time.

She scoffed at herself. Why rush an activity that gave her so much joy? Surely, the work she loved and delighted in would suffer. She would suffer. Her enjoyment came in the discovery, in the process of painting and layering colors rather than in completing a work to sell. “I might as well be a machine in a factory!”

Remy turned to her as though asking for an explanation, so she obliged. “I would feel nothing. And if I feel nothing, how can I expect my paintings to inspire anyone?”

Then again, she needed to earn more. If only she could draw higher prices… If only she could paint portraits! She groaned at the vicious circle that kept her trapped .

Longbourn came into view, a welcome distraction from her frustration. Her father’s carriage sat in the drive. He had returned from London. She prayed he bore good news, though in her experience, appointments with the banker seldom did.

He alighted from the conveyance, refusing Mr. Hill’s assistance. Instead, he pulled out a crate, which he cradled like a baby in his arms. Elizabeth frowned in confusion. Papa’s trip to London had been for business, not pleasure. Mama was certain to complain when she learned he had gone shopping without her. So intent was he on the crate that he did not notice Elizabeth follow him inside. Her mother and sisters swirled around him as he carefully set the crate down on one end of the breakfast table, completely impervious to the dishes he nudged out of the way as well as Mama’s warnings that he not snag the tablecloth.

“Was London a success, Papa?” Elizabeth asked, her anxiety winning out over her curiosity. If the financial institution did not extend her father’s loan, they would have no money to buy seed to plant in the spring.

With a nod and a mumble, he carefully pried off the lid and set it against the table leg. Elizabeth leaned forward impatiently to see what captured her father’s attention so fully.

Nestled on a bed of straw was a painting smaller than the atlas in her father’s library. She had hardly caught a glimpse of it when he lifted it from the straw and held it up for the occupants seated at the table to see .

Mama huffed and made a big to-do over her breakfast roll, tearing the bread in half and spooning generous helpings of fruit preserves on top in an apparent attempt to drown her disappointment in strawberries. Lydia was soon to follow, as was Kitty. Soon, Papa had the privilege of being glared at by the threesome while he held his painting as though it were the most precious masterpiece in the world. Mary took her place quietly and sipped from her teacup, clearly not knowing what to think. Truth be told, Elizabeth did not know what to think, either.

Jane, always the one to pacify and appease, said, “I have never seen such a beautiful work of art. Will it not look lovely in the front parlor, Mama?”

At this, Papa jolted from his reverie. “Absolutely not! Such a splendid display of technique and artistry must be protected and safeguarded.”

Mama stabbed her spoon into the jar of strawberry preserves. “You refuse to allow me and the girls to go to London for a shopping expedition with you, then you come home with a painting you will not allow us to see?”

“Come, my dear, you know very well that the purpose of my trip was to meet with the banker.”

Elizabeth sucked in a breath, but Papa gave her no significant look, nor did he seem inclined to say anything more on the subject. “I came upon this quite by accident, I assure you. When the door is open to my study, you will have plenty of occasions to see it hanging behind my desk from the hall. ”

“Mr. Bennet, how can you be so cruel to me? After all I suffer, with all I endure?” Mama shoved the berry-smothered roll into her mouth.

Papa turned the painting to face him, the ever-present twinkle in his eyes. “Yes, I can see how dearly you suffer, my dear. Shall I ask Hill to bring you more preserves?”

Mama’s chin trembled. “This is the last jar,” she said through a sniffle.

Elizabeth’s sisters lost interest in the painting when they realized how little fruit remained for them―all except for Jane, who went to the kitchen, no doubt searching for something that would distract them from their disappointment.

Papa, not one to be preoccupied with food, carried his painting into his study. Elizabeth followed, anxious to hear his news and to get a closer look at the piece.

“Papa, what did the banker?—?”

He held up his hand to his lips. “Shhhhh. Just look, Lizzy. Have you ever seen its like?”

Elizabeth looked. The worries of moments ago were instantly forgotten with her senses too full of wonder, excitement, inspiration, hope… and other emotions she could not even name. She had not had the opportunity to frequent art exhibitions in town, but she had memorized every print inside her father’s books. This, this glorious painting, was the work of a master!

She stepped closer, her hands over her heart, drinking in its beauty thirstily. The contrast of shade and light, the Divine theme peeking behind every stroke of the brush, the style. She recognized the work of an artist whose skill she had dreamed of being able to one day see for herself. “Rembrandt?” she whispered.

“Stunning, is it not?” Papa replied in a church whisper.

It was stunning. Elizabeth had heard of painters who copied original works, most of them to practice and improve their own skills, but she had never seen one before. She had thought them audacious and overreaching for selling their imitations. However, now that she stood directly in front of one of their reproductions—and an exceptional reproduction it was!—she could only feel gratitude. Only royalty and established families with connections and great wealth displayed original art in their galleries. She never would have had the chance to see this beautiful painting had the artist of this work not taken the time to copy it so expertly. “It is a skillful reproduction. How did you come upon it?”

“Would you believe I bought it from a vendor on the street?”

Elizabeth gasped. “Sacrilege!” She dared not ask how much he paid. Any sum was too much.

He took her hand between his, his touch comforting and warm. “We are saved, Lizzy. All is well.”

She wanted to believe him so badly it hurt. Art had always been his solace, much as it was hers, but he did not paint anymore. All he had were his books… and now, this painting.

Not a trace of worry wrinkled his brow or scrunched his eyes. At that moment, her father looked happy and free of the fears that had buried him and his estate under a mound of poor decisions and debt. She could not bring herself to ruin it by inquiring any further about the banker.

Her own worry, however, intensified.

Fullepub

Fullepub