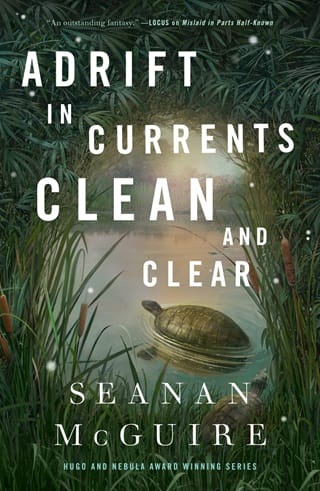

13. The Edge of the Pond

13

THE EDGE OF THE POND

HANDS GRIPPED HER SHOULDERS and yanked her back into the air. Nadya hung limp, barely aware, as she was laid down on a surface of hard-packed mud. “—she’s breathing,” said a voice, unfamiliar, strangely accented, with none of the gentle slopes she had come to understand in the city beneath the River Wild.

Perhaps she had found the other city’s survivors after all? A hand pressed down on her chest and water bubbled up her throat, filling her mouth. She rolled to the side, vomiting it out, and opened her eyes at the same time, looking down.

She was sprawled on some kind of bank, not on a city dock as she would have expected. Two strangers stood nearby, oddly dressed in blue trousers and thin printed tops, no embroidery, no texture. They were watching her with concern.

“Are you all right, little girl?” one of them asked.

“I’ve seen her around the neighborhood,” said the other. “She’s that little Russian orphan Carl and Pansy adopted.”

Nadya choked up more water and looked down at herself, horrified but somehow not surprised to see her body as it had looked when she was ten going on eleven, and not as it had looked when she rose from her bed that morning, a woman grown and ready to ride out for the service of her city, river, and home.

Her water arm was gone, replaced by the absence that had been familiar for so very long, but was now only an aching confirmation of what had happened.

Nadya pushed her feet back under herself and braced her left hand against the mud, levering her body into a standing position. Everything about the motion felt odd. She was too small, too light; there was nothing to her.

The people who had pulled her out of the turtle pond watched her silently, concern in their faces.

“What…” she began. “What happened?”

“I saw you floating in the water, facedown, and pulled you out,” said the first stranger. “You would have drowned if I hadn’t come along when I did.”

Nadya looked frantically around. Nothing she could see looked even remotely like a door. The pattern of weed and shadow had been hopelessly disrupted by her fall, the fence was the wrong angle, nothing was right…

Nothing was right.

Her prosthetic arm wasn’t floating in the pond, and Belyyreka was still a memory, bright and burning, not fading like a dream. She knew who she was. She knew where she belonged. She turned to run, and stopped as one of the people grabbed the back of her jacket, pulling her to a halt.

“Stay here, little miss, while we call your parents and get you seen to,” he said.

Nadya didn’t struggle.

She no longer remembered the way home from the edge of the water, after all.

Fullepub

Fullepub