Chapter 2

2

MAY 21, 1927 PARIS, FRANCE

The next morning, I awoke in the H?tel Westminster in the heart of Paris, but my pulse was still hammering from my escape in 1727. It would be dangerous to travel as a single woman for the thirty miles from Huger to Charleston, so I had borrowed a set of the stable boy's clothes from the wash line behind the kitchen. He would miss them, but I was desperate.

Most men wore their hair shoulder-length and clubbed at the back with a ribbon. My hair went past my waist, so I had cut it with trembling hands and wore a red handkerchief under the leather tricorn hat I borrowed from a hook in the kitchen. I'd also taken a pair of buckled shoes from the back porch that belonged to one of the servants. They were a little too big for me, but they would have to do.

Before I left, I slipped my diamond necklace into my pocket. It had been a gift from my grandfather on my eighteenth birthday, and I would sell it for passage to Nassau.

With nothing but the clothes on my back and the necklace in my pocket, I set out on foot, walking and running as far as I could throughout the night until I fell into an exhausted sleep hidden in a cover of trees about a mile outside Charleston.

But now I was in Paris again and would have to wait an entire day to wake up in 1727 and continue my escape. Grandfather would come looking for me, so I had to get onto a ship as fast as possible. It was my one chance to learn the truth about my mother and see if she could help me understand the strange existence we shared.

The Paris street was already loud and busy outside my hotel window as I quickly threw back the covers and got out of bed.

"Wake up, Irene," I said as I chose a simple, modest dress with long sleeves and a dropped waist. The dress might not be as glamorous as the dresses I admired on others, but it was much more comfortable than my stays and heavy skirts in 1727.

My cousin Irene was in the bed next to mine and moaned, "Leave me alone, Caroline."

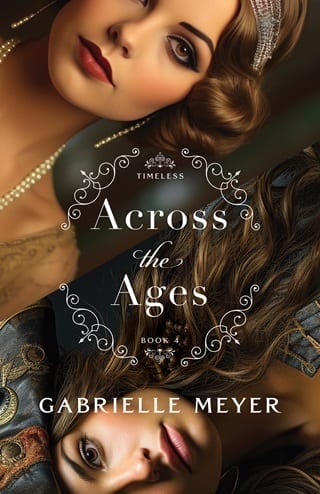

My first name was the same in 1727 and 1927, something that always amazed me. But my last names were different. In 1727, I was Caroline Reed, the daughter of young Anne Reed and her sea merchant husband. Even if Grandfather knew the name of Anne's husband, he had chosen to give me his last name. In 1927, I was Caroline Baldwin, the daughter of the Reverend Daniel and Mrs. Marian Baldwin. Passionate reformers, prohibitionists, and devout Christians.

"We can't make Father late," I told her, tired of the game we played every morning. She was just a few months older than me and had been invited along on our trip to be my companion—yet I knew the truth. Irene's father had passed away last fall, and since then my cousin had become reckless. She'd cut her hair short, wore provocative clothing, began to smoke cigarettes, and went around with a loose crowd. My parents had hoped to reform her on this trip. So far, nothing had changed, and I had spent most of my time trying to keep her from embarrassing my father. But I'd quickly come to realize she didn't need reforming. Her heart was grieving, and she needed time to heal. The rebelliousness distracted her from the pain.

I shook her shoulder. "Irene," I said with a little more force. "Today is an important one for Father—perhaps the most important. You must hurry."

With another groan, she rolled onto her back and yawned. "I thought coming to Paris would be fun."

"You knew we were coming to attend the conference."

Irene lifted herself onto her elbows and blinked away the sleep. Her short blond bob was in a net to protect the marcel waves while she slept. Mother and Father refused to let her wear makeup, but there was a hint of color on her lips and rouge on her cheeks.

Neither had been there last night when we went to sleep.

"Did you go out last night?" I asked.

A saucy smile tilted her lips. "I had to have some fun, Caroline. I couldn't go back to Des Moines without something to tell my friends. And boy, was it the cat's pajamas!"

We'd been in the City of Lights for two weeks and had spent most of our time sitting through boring lectures, meetings, and sermons. Father had been invited to speak at the World Conference of Christian Living. It was a summit that included leaders from denominations all over the world, seeking unity and understanding amidst the social chaos of the Roaring Twenties. As one of the most prominent and outspoken preachers in America, Father had been asked to attend. He was known for his fiery sermons and the large tent revivals he hosted across America. But it was his ardent support of Prohibition that had made him famous, by friends and enemies alike.

Some called Prohibition a failed social experiment and were advocating for its demise. Father was working hard to ensure its success—and he'd enlisted my help, though I'd been given little choice.

"What if you were seen?" I asked her, whispering so my parents wouldn't hear in the connecting room. "What would people say if they knew Reverend Baldwin's niece was cavorting on the streets of Paris—at night?"

Irene tossed her covers aside and sat up to stretch. "Don't spoil this for me. I had so much fun last night at the Dingo Bar—and I plan to go back." Her blue eyes were shining. "Do you know who I met? You'll never guess. Ernest Hemingway! The author. And he said that F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda, would be there tonight! Can you imagine? The Great Gatsby is the bee's knees. Fitzgerald is one of the greatest literary minds of our time, and I'm going to meet him."

A longing filled my heart that surprised me. Books were one of my favorite pastimes, and to meet an author like Ernest Hemingway or F. Scott Fitzgerald was a dream. But I could never take the risks Irene had taken. Fear of disappointing my parents, and bringing shame to our family, was always on my mind. I was supposed to uphold the ideals and morals that Father preached—no matter how much pressure it created. "You can't return. If someone sees you—"

"No one cares." Irene stood and touched her hairnet. "They don't care about your father or what he has to say—they don't really care about any of the old rules that used to matter. There are no pretenses with this crowd. No right or wrong. The war changed everything—it woke people up, and now they're living their lives however they want. And that's what I'm going to do, too. We're leaving Paris tomorrow, and I won't miss an opportunity to meet F. Scott Fitzgerald—even if your father locks me in this room."

The door to the connecting room creaked open, and Mother appeared, a pleasant smile on her pretty face. "Good. You're up. We'll be heading down to breakfast in twenty minutes. We mustn't be late."

"Of course, Aunt Marian," Irene said with a placating smile. "We'll meet you down there."

Mother closed the door again, and I faced Irene. "You're not returning to the Dingo Bar."

Just like 1727, there were expectations placed on me here. The only difference was that I didn't have to marry a man I didn't love, and I had more opportunities and comforts in 1927. Beyond that—my life was not my own.

What would it be like to live a life of my own choosing—both here and in 1727? I was almost too afraid to wonder. Reaching for something I couldn't have would only bring disappointment and regret.

Irene dismissed me with a bat of her eyelashes as she entered the bathroom and closed the door tightly, humming loud enough for me to hear.

By the time she left the bathroom, I had to rush in to finish getting dressed, and then we raced to the hotel restaurant where my parents were already eating. After a quick breakfast, we exited the building and entered the vehicle waiting to take us to the conference.

Father was silent as he looked over his sermon notes, encouraging other countries to follow America's lead and abolish alcohol. He was a handsome man in his late fifties. Tall and athletically built. He'd been a baseball player in his early twenties before turning his life over to Christ and pursuing a ministry as a pastor and reformer.

Mother was small and gentle in comparison, but her size was no indicator of her strength. She stood passionately alongside my father, supporting every move he made and advocating for her own beliefs and opinions. They were an admirable couple whom I respected deeply, even if their ministry felt too heavy for my shoulders. I often wondered if I hadn't been born with the uncertainty that came with two lives, and the possibility that my grandmother was hanged as a witch in Salem, would I have been more confident in my role as their daughter?

Irene looked out the window as we drove down the Avenue de Friedland and around the Arc de Triomphe. She'd washed her face and was wearing a modest dress, but I suspected she was thinking about her escape the night before, making me curious as to how many other nights she had snuck out.

We finally arrived at the Bois de Boulogne, a magnificent park in Paris that housed several venues that had been used for the conference. Hundreds of people were enjoying the beautiful morning, strolling through the landscaped park, riding the merry-go-round, and fishing in the ponds.

The driver opened the back door for our family.

Father stepped out first, Mother followed, and then I exited after Irene.

"Lindbergh! Lindbergh!" A bedraggled newsboy ran up to us, holding a newspaper aloft in our faces, his hands smudged with ink. " Aviateur Américain !"

"What is he saying?" Father asked Mother.

The boy was speaking quickly in his native tongue. Since Mother spoke French, she listened and nodded several times.

"Another American pilot has attempted to make a flight from New York to Paris for the Orteig Prize," Mother explained to Father. "He left New York yesterday and, if he makes it, will land in Le Bourget airfield just outside Paris tonight."

Irene's eyes opened wide as she tried to peer over Mother's shoulder at the newspaper she couldn't read.

"Please purchase the paper from him, Caroline," Father said as he offered his arm to Mother and led her toward the amphitheater.

I pulled five centimes from my purse and purchased the newspaper, but before I could tuck it under my arm, Irene grabbed it.

"This is so exciting!" she said. "Imagine if he makes it."

I said, " Merci ," to the newsboy and wrapped my arm through Irene's to tug her along as we caught up to my parents.

Mother, Irene, and I were ushered to seats at the front of the amphitheater as Father went behind the stage to meet with the organizers. I felt hundreds of eyes upon us as we took our seats. Mother kept a placid smile on her face, but I felt fidgety. Not only because we were the center of attention, but because I was anxious about my escape in 1727. As soon as I woke up there, I would need to work quickly.

I longed to speak to Mother about what was happening in 1727, but just like Nanny, Mother had hushed me as a child, admonishing me not to lie. But when I insisted my second life was real, she brought the matter to my father, who threatened to discipline me if I didn't hold my tongue. I hadn't breathed a word of it since then.

Mother took the newspaper from Irene as she said to me, "Stop fidgeting, Caroline. Do you want the others to think you're nervous? They might wonder why the daughter of a preacher would be nervous. We don't want them to think you're hiding something."

Irene's smug smile made me stop trying to get comfortable in my seat. Why did she seem so calm about her secrets? How did she not feel condemnation and guilt, knowing she had run out last night to spend time in a bar?

It was just one more secret I had to keep from my parents and from the teeming masses who either wanted to elevate Father to sainthood or ensure his complete demise. The responsibility to appear perfect on such a worldwide scale was suffocating. My brothers had folded under the demands and chosen their own paths, though my parents had no idea the double lives they were living. Just like Irene, they showed no signs of guilt or shame.

I, on the other hand, felt smothered under the weight of the smallest transgression. Everything I did was scrutinized. Father's calling to serve God had placed me on an unwanted pedestal. And, if that wasn't enough, his vision for evangelism was grand and impressive.

Was it not enough to serve God with an ordinary and humble life?

Mother glanced at the newspaper as she was about to set it aside, but then she paused. "This Lindbergh fellow is from Minnesota."

"Minnesota?" Irene's interest was piqued again.

I looked closer at the paper, surprised, because we lived in Minneapolis. We would board a ship tomorrow to make our return trip to America, arriving in New York and then going by train to Minneapolis and home. Irene would return to Des Moines and her fretful mother.

When the program finally started, the amphitheater was packed. All eighteen hundred seats were full, and hundreds more were standing around the edges.

Father motioned for me to join him.

I trembled as I took the stage. Though I'd done this dozens of times, it never got easier.

"We'll sing ‘Rock of Ages' and ‘Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing,'" Father said to me.

I nodded and then took my place in the center of the stage where the microphone had been placed.

"Please join me in singing ‘Rock of Ages,'" I said into the microphone.

As I began to sing, the amphitheater filled with my voice, and the audience joined me. Mother's eyes lit up with pride and joy.

Ever since I was young, people had praised my voice, and Father insisted it was a gift from God. To me, it was another burden. If I could sing for pleasure alone, I would love it. But singing for an audience who judged each note robbed me of joy.

After both songs were finished, I took my seat next to Mother again, my cheeks warm and my heart pumping with relief.

"Before I hand the microphone over to Reverend Baldwin," the organizer said in English, while a translator interpreted in French, "I want to make a special announcement. Reverend Baldwin has just agreed to host a weekly international radio broadcast program. It will be the first of its kind, and, we hope, will further our mission to eradicate alcohol use around the world."

The audience cheered enthusiastically as Mother and I looked at each other in surprise. I didn't know of any other pastor who had an international audience.

My heart started pounding for a whole new reason. It terrified me to think about my brothers' secrets getting out. Father's entire ministry would come crumbling down, and thousands of people would be disillusioned.

After all, what good was a pastor's preaching when one of his sons was a gangster and the other was a crooked cop, taking bribes from criminals?

The lights of Paris sparkled as the sun set on our last day in France. I had left the window open to allow the fresh air to flood our room, filling it with the fragrance of spring and the sounds of people at sidewalk cafés or passing by on the street. I wasn't ready to go to sleep in Paris—to face my escape in Charleston. I wanted to lie for a few minutes and enjoy this moment of tranquility. This breath between my two lives.

Ever since I was young, I could choose when I wanted to fall asleep. I would simply lie down, close my eyes, and fall into a deep slumber. If midnight came and went while I slept, I would wake up in my other life. But if I stayed awake past midnight, as was common while at a tent revival with Father, I would not cross over until I went to sleep. If I wanted to nap during the day, I would remain in whatever life I was in, as long as I woke up before midnight.

Somehow, I woke up refreshed in body—if not in soul or spirit.

The room was dark fifteen minutes later as I heard the rustle of Irene's bedding. When I turned, I was shocked to find that she had been under her covers fully dressed—shoes and all—and she was sneaking out of our room.

"Irene," I said in a loud whisper.

She opened the door and stepped into the hall. "Go back to sleep, Carrie. This doesn't concern you."

And, with that, she closed the door and was gone.

I tossed my covers aside and quickly began to dress. I put on the same clothing I'd worn earlier that evening to the farewell dinner. My gown was modest, but it was probably the most fashionable thing I owned. With layers of black silk and lace, it extended to my mid-calves and had a dropped waist. But it was the shawl, made of the same black lace, that had made Mother approve. She had not let me cut my brown hair short, like Irene's, so I had found a way to roll it up to make it look like the shorter styles, with marcel waves framing my face.

As I made my way toward the door, I slipped my black heels onto my feet, but I left my hat and purse behind.

I needed to stop Irene before she left the hotel.

Thankfully, my parents' connecting room had been silent since nine. I just prayed they wouldn't wake up and discover neither of us in our beds.

I didn't see Irene in the hallway or on the stairs. She wasn't in the lobby or just outside the hotel, either.

Traffic moved past the H?tel Westminster as people walked toward the Place Vendome, a large public square nearby. I moved in that same direction, my eyes scanning the street as I neared the large obelisk in the center of the plaza. Nightclubs, cabaret shows, and jazz clubs beckoned on this cool night. If Irene hadn't told me she was returning to the Dingo Bar, I would have thought of looking in one of them.

I caught a glimpse of my cousin as she took a left to head toward the Jardin des Tuileries, a beautiful garden along the river Seine.

"Irene!" I called out to her, heedless of the French men and women who turned toward me as I began to jog in her direction.

"Irene," I yelled again.

Finally, she stopped. When I caught up to her, she asked, "What are you doing, Carrie?"

She was wearing a dress I hadn't yet seen. It was ruby red and shimmered under the glow of the lamps. The hem was at her knees, and the décolletage dipped dangerously low. She wore no brassiere or undergarments and was covered in long, black necklaces, earrings, and a black headdress with more dangling jewels. Her outfit was so shocking, my mouth slipped open.

"What am I doing?" I stared at her. "What are you doing?"

"I told you." She continued to walk with determination toward the Jardin des Tuileries. "I'm going to meet F. Scott Fitzgerald."

I raced to keep up with her, wishing I had the same courage as Irene—or was it foolishness? To the left was the famous Louvre Museum, and to the right, at quite a distance, was the Champs- élysées. I could glimpse the top of the Eiffel Tower, though it was shadowed in the night sky.

"You can't go—"

"There's no use trying to stop me," she said as we walked through the Jardin des Tuileries, toward the Pont Royal bridge. "You can come with, if you want." She looked me up and down and wrinkled her nose. "Though you look like a frump in that getup."

I paused for a second, my heart longing for something my head knew was reckless. Irene was going, whether I liked it or not. I could either return to our hotel and pray she got back before my parents woke up, or I could go with her and try to get her back at a reasonable hour.

I had a feeling that either way, I would regret my decision.

"Wait for me," I said.

She slowed her pace and grinned as she wrapped her arm through mine. "I knew you'd come to your senses."

"We're going to regret this," I told her, feeling both excitement and guilt. I couldn't believe I was going to a bar. Even though alcohol was legal in France, if anyone found out where I'd been, it wouldn't bode well.

"Maybe you will—but I won't. What can Uncle Daniel do to me? Send me back to my mother? I'm heading that way tomorrow anyway."

She hailed a taxi just over the bridge to take us the rest of the way.

When we got into the back seat, she told the driver to take us to the American nightclub called the Dingo Bar at 10 rue Delambre in the Montparnasse Quarter.

"It's open all night," she told me as she pulled a tube of lipstick and a pocket mirror from her purse. With the aid of the streetlights, she began to apply it liberally to her lips. "It's a popular gathering place for the Lost Generation. You know who they are, don't you?"

I sighed. "Of course I do." They were Americans disillusioned after the Great War, the Spanish flu, and Prohibition, who saw their lives as fleeting. Too short to waste. They were grasping hold of the fragility and opining about its faults in their novels, poetry, and artwork. "I hope none of them recognize us."

Irene offered me the lipstick, but I shook my head. It wasn't that I disagreed with the use of lipstick, but that I would be in enough trouble with my parents already.

She applied her rouge next and rolled her eyes. "If you need to use an alias, I won't stop you. But I'm telling you, none of them care about you or your father."

"I can't take any chances."

We arrived at the Dingo Bar a few minutes later. It wasn't remarkable or even attractive. Nothing like the Moulin Rouge, with its red windmill atop the roof. Instead, it was a simple building in a row of buildings, with an awning that said Dingo American Bar and Restaurant. The windows were covered with curtains, not allowing us to see inside without entering.

Irene paid the taxi driver as I left the vehicle. She joined me a moment later.

"Ready?" she asked, her blue eyes lighting up with excitement.

I'd never been to a nightclub—had no idea what I was doing there—but Irene didn't give me time to think about it. She pulled open the door and sashayed into the bar as if she'd done it a dozen times—and perhaps she had.

"They say Lindbergh should have landed by now," a man said to another in an American accent as I followed her in. "I'd lay odds that he crashed in the Atlantic and no one will remember his name a month from now."

"I think he still has time," said the other. "We'll be hearing about his landing any second."

The room was long and narrow with a dark paneled bar on one side and a small stage at the back. There were dozens of tables, some in the middle and others along the outer wall. Pillars were interspersed throughout, giving people a little privacy. Were any of these men Hemingway or Fitzgerald?

"Lindbergh, Lindbergh, Lindbergh," Irene laughed. "That's all I've heard today. We should have gone out to the airfield to watch him land."

"What are we supposed to do now?" I asked Irene as she scanned the room.

A smile tilted her red-tinted lips. "We mingle and wait for Fitzgerald."

Several people looked in our direction as cigarette smoke swirled over their heads. They couldn't possibly know who I was by looking at me—and I wasn't going to tell them. They would recognize my father's name as part of the problem with America, but I was rarely in the newspapers. If I kept my identity to myself, my parents would never know I'd been there.

"There you are," a man said to Irene as he approached. He was probably in his late twenties, handsome, with intelligent eyes and a dimple in his left cheek when he smiled.

"Mr. Hemingway," Irene said in a voice that didn't sound like hers. "I was hoping to see you again."

This was Ernest Hemingway? My pulse pounded as I tried to remember to breathe.

His gaze slipped to me, and he took me in from head to toe, a curious look in his eyes. "Are you going to introduce me to your friend?"

Irene hadn't needed the rouge, since her cheeks were bright with color. "This is my cousin, Caroline B—"

"Reed," I said. "Caroline Reed."

"You sound Midwestern, too," he said with a chuckle.

I lifted my eyebrows, his easy demeanor relieving my nerves. "You could tell from three simple words?"

His grin was infectious. "You've got that innocent, wholesome look about you. Not to mention, I'm from the Midwest, so I know one when I see one." He put out his hand and said, "Ernest Hemingway. It's nice to meet you, Miss Reed."

"My pleasure." I wanted to tell him how much I'd enjoyed The Sun Also Rises , even though I'd had to read it in secret since Father shunned anything that came from this so-called Lost Generation. But I couldn't find the words.

"Jimmie," Mr. Hemingway said, rapping on the bar. "These girls need a stiff drink."

"No." I quickly shook my head. "No, thank you. I don't drink."

"I'll take one," Irene said with a giggle.

After Hemingway ordered a drink for Irene, he turned back to us. "Fitzgerald isn't here yet, but he should be along shortly."

Disappointment lowered Irene's shoulders and caught me off guard, too. I shouldn't have been so eager to meet these men—but I couldn't help it. Their books were popular because they reflected the thoughts and feelings of this generation. Even though my parents tried to shelter me, I was still intrigued. Perhaps even more so because I felt foolish not knowing what others knew.

"Don't fret," Hemingway said. "We can have a good time while we wait." He glanced at the empty stage. "If we had some music, we could even dance."

"Caroline sings," Irene said, much too eagerly. "She sings all the time."

"Is that right?" Hemingway's face filled with interest. "We haven't had music in here for days." He took my hand and led me through the maze of tables, laughing as he bumped into people, leaving me to apologize in our wake.

"Really, Mr. Hemingway," I protested as I tried to pull away. "I'm not going to sing here."

"Sure you are. And I'll accompany you." He led me up a short flight of stairs to the stage. "My mother is a musician, and she forced me to learn the cello. It comes in handy now and again." He motioned toward a cello sitting on the stage. "It hasn't been played nearly enough. What do you want to sing?"

"I don't want to sing."

"Come on," he said, his handsome smile almost blinding. "You're young, beautiful, and, if your cousin is right, talented. Life is too short to be bashful or modest. If you have it, use it. What'll it be, Miss Reed?"

He was still holding my hand, probably afraid I'd bolt if he let go.

People had noticed us on the stage, and several were watching with mild curiosity. Irene had found a table and was waiting with expectation.

But I couldn't do it. I only sang in public because I felt obligated to Father. I had no such obligations to Ernest Hemingway.

"I'm sorry," I said as I shook my head and pulled away.

"Miss Baldwin," Hemingway said as he stepped to the edge of the stage to address Irene. "Can't you convince her?"

Irene jumped up from her seat and met me at the base of the steps. "Please sing, Caroline. I'll do anything for you. I promise."

I paused. "Will you leave this place when I'm done? Return to the hotel with me?"

Her face fell. "I don't want to leave yet."

"Then I'm not singing." I began to move around her.

"Come on," Hemingway said.

"Please don't embarrass me in front of him," Irene begged.

"Promise me we'll leave as soon as I'm done," I told her, even though I wanted to meet Fitzgerald. The longer we stayed, the more we risked getting in trouble.

Most of the occupants of the bar were now watching, since Mr. Hemingway made no attempt to be discreet.

"Fine," she said, almost angry. "We'll leave when you're done."

"Good." I climbed the stairs again as Mr. Hemingway whistled his approval.

The crowd clapped, and Irene returned to the table, shooting daggers at me with her eyes.

"What'll it be?" Hemingway asked me as he took a seat behind his cello.

"I suppose you don't know ‘Amazing Grace' or ‘Rock of Ages,' do you?"

He laughed, hard. "I do," he said, "but I don't think this crowd will appreciate either one. How about ‘Downhearted Blues'?"

It was a popular song, one I'd heard Irene sing several times since our journey began.

"Alright." I gripped the microphone like an anchor, trying not to look as nervous as I felt.

Almost every gaze was on me as Mr. Hemingway began to play.

I closed my eyes, trying to block out the room and remember the lyrics that I'd only heard a few times.

The entire room was silent as I sang. I slowly opened my eyes and found their attention was riveted to me and the stage. Several of them were smiling and tapping their toes.

There were no judgmental stares, no one whispering behind their hands, and the weight of my father's reputation was nowhere to be found.

A smile lifted my cheeks, and for the first time in my life, I didn't hate singing in front of an audience. It was a strange and liberating feeling.

When the song came to an end, there was a brief pause, and then the room erupted into applause. They cheered and stamped their feet, calling for an encore.

I grinned. I couldn't help it.

The door of the Dingo Bar flew open, and a man ran inside shouting, "Lindbergh did it! He made it to Paris! Vive Lindbergh!"

The Minnesota boy had made it across the Atlantic Ocean all by himself.

Everyone left the bar to join the celebration in the street.

Mr. Hemingway was at my elbow, a smile on his face. "Come on, Miss Reed. Let's go commemorate this amazing feat of mankind. The first person has flown an airplane across the ocean. For better or worse, our world just got a whole lot smaller."

I didn't care about the world. All I cared about was finding Irene and returning to the hotel before my parents knew we were gone—and before I could think too hard about what I had just done or why it had felt so good.

Fullepub

Fullepub