Chapter Eleven

M ama waited until the next day to give her lecture. Helen wore her favourite old dress and her hair braided down her back. She didn't like the weight of it on the top of her head. It felt as if it pressed her down to the earth like Newton's laws of gravity. Donning her straw hat, she was about to put on her work gloves and climb over to Mark's back garden. She'd already finished watering all the plants in the conservatory and trimming off the dead blooms.

Her mother stood between her and the door. ‘We made a bargain, Helen.'

She tilted her chin up. ‘I danced most of the night. You know I do not like to stay up late. And these infernal ton balls go on until the wee hours of the morning.'

‘You cannot simply slip into someone's library and take a nap. What if someone had found you? What if a gentleman had taken advantage of you?'

Helen gulped.

Samuel hadn't told Mama that he'd found Mark with Helen. She felt a tinge of guilt for every rude thing she'd ever said to him and all the terrible things she helped Frederica do to him when they were children. The snake in his bed and the bear cub in his room. The salt in his tea. The list went on. And Helen had been a very willing participant in all the pranks.

‘Technically he wouldn't have been a gentleman, then.'

Her mother stepped closer, her hands on her hips. ‘You could have been compromised.'

‘I can't be compromised, because I wouldn't allow external forces to decide how I feel internally. And I wouldn't mind being ostracised by the ton , which is what you actually mean. I am not like the rest of them, Mama. You know this. I am a different sort of creature entirely.'

Mama sighed. ‘Lady Glencannon said that you insulted her son.'

‘I simply pointed out that the Bible was written by men and that wives did not have to be obedient to their husbands. If he chose to take offence at my words, I hope it is a stone fence and that it crushes his bones to dust.'

Her mother didn't laugh at her very poor play on words. ‘Helen, what am I to do with you?'

‘You remember Henrietta?'

‘How does one forget a caracal?'

Helen tugged at the end of her braid. ‘She died, Mama. After only two years in England. It wasn't because she lacked food or love. We did our very best, but she still died because this wasn't her natural habitat. London parties and the ton are not mine. I was meant to be near Hampford Castle. Near the river and in the wide-open spaces. Among naturalists and scientists...thinkers. I don't belong in a ballroom any more than a wild boar.'

Mama took Helen's cheeks between her hands. ‘You are my daughter. There is no place that you do not belong.'

Twisting away, Helen sighed. ‘You don't even care that I hate it here.'

‘Of course I care. But, Helen, you can't escape from who you are. You are not a bird or a snake. You are the daughter of a duke. And as much as it is delightful to imagine living in nature, you would miss exquisitely cooked meals, your family, your soft, warm bed and hot baths.'

‘Then why won't you let me marry Jason? Is it because you think he's a different creature entirely because he's a curate and not an aristocrat?'

Her mother folded her arms across her ample chest, the one that Helen had not inherited. ‘I have great affection for Jason. He was my daughters' dearest friend growing up, but I like him for his own sake as well. I have never met a person with a cheerier disposition who is both discerning and intelligent.'

Helen stuck out her chin. ‘Then what is your opposition to our marriage?'

‘You are.'

‘What?'

‘You would make Jason a terrible wife.'

Rubbing her eyes, she took a few shaky breaths. ‘Why...why would you say that? You're my mother.'

Mama stepped closer and put a tentative hand on Helen's arm. ‘I am your mother and I love you more than you will probably ever know. And I want your happiness more than anything and that is why I have opposed the match.'

Helen snorted. ‘Because he isn't wealthy or titled?'

‘Because Jason has chosen the church for his profession,' her mother said, gently squeezing Helen's arm. ‘There are expectations for his behaviour in the parish, as well as his wife's. What is charmingly eccentric and admissible behaviour in the daughter of a duke would be highly inappropriate for a vicar's wife.

‘You would be expected to behave above circumspection. You could not go out on your own to explore nature. You would be expected to stay at home unless you were accompanied by a servant or another female. You would not be able to say what you think. If you offended the wrong people, you would cost your husband his living. And publishing your own writing would be considered scandalous and outrageous. You would be blackballed from the local society. The vicar's wife is supposed to be a pattern card of obedience, virtue and submissiveness. I'm sure you would fail on all three counts.'

Helen tore away from her mother a second time, feeling as if the truth of her words had clawed her skin like a puma. What if the life she had imagined with Jason in the country was nothing more than a dream? ‘You don't believe in me at all.'

Her mother held up her hands. ‘I do believe in you and I love you exactly how you are. That is why I do not want you to have to change. But if you marry Jason, you will have to, or you will both be miserable. Not even his cheery disposition could overcome the censure and scorn you would receive as a couple. He would be held to blame for not keeping you in check and the last thing he would ever do is try to tame you. Not that he could.'

Helen couldn't bear to hear any more. She spun on her foot and ran up the stairs to her room. Flinging herself on her bed, she decided that Mama was right about one thing: even if Helen was a wild beast, she did like soft mattresses.

Mark had received a pile of invitations for dinner parties. He had declined every single one. Matchmaking mamas were truly the most terrifying creatures in existence. Most debutantes were only seventeen years old and they seemed like children to him. Awkward, coltish and not yet fully grown. And likely to be horrified by his missing limb. He felt decades older than them in life experiences and more like a grandfather than a suitor. Not that he wished to be a suitor to any of them.

He told himself he'd accepted the Duchess of Hampford's invitation because she was a formidable woman and not used to receiving no for an answer, but that wasn't it. He couldn't fool himself. He was coming because of Helen. Because she made him laugh. Because she didn't make him feel like a cripple. Because he never knew what she was going to say next. Because she was already secretly engaged to someone else and she didn't want to marry him. Because she made him feel like a real man again.

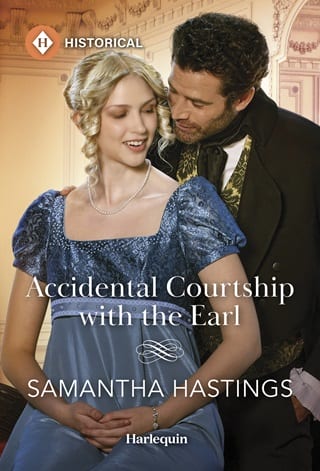

He wore his ‘Cossack' silk trousers lined with linen, even though he suspected that every other male of the party would be wearing knee breeches. He had no desire to show off his wooden leg. Mark missed wearing kilts. Still, his new dark blue double-breasted tailcoat with gilt brass buttons was stylish, with overlapping collar points called a ‘lark's tongue.' The collar was also notched with the letter ‘M' on both sides.

Content with his appearance, Mark went out to his carriage. Hampford House was a short distance and in the past he would have walked it. But he didn't want to arrive out of breath and sweaty.

Mark was ushered into a spacious room where the Duchess of Pelford was playing the piano and other guests were speaking. Helen smiled when she saw him and came bounding up to him at a speed he could no longer manage. He thought she might bowl him right over, but she stopped just short of him, the fabric of her dress covering his boots. Helen was not wearing her usual white, but an indigo-blue dress with little puffed sleeves that looked as though they were from a Tudor painting: ivory-coloured silks billowed out of the four little openings on each sleeve. Below the puffs were long sleeves that went all the way to her narrow wrists, where there were double bands at the cuffs and more ivory silk frills and ribbon. Blue ribbons had been woven into her pale hair. Helen had never looked more like Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queen .

She beamed up at him. ‘You came.'

He couldn't help but smile back at her. ‘As you can see.'

Helen put her arm through his without waiting for him to offer it, leading him to a sofa on the other side of the room. ‘It's best to get some distance when Frederica is fighting the piano or I will not be able to hear you.'

Mark laughed. ‘She is certainly playing it with great gusto—but she plays beautifully.'

‘She's clearly winning the battle,' Helen agreed, her arm still through his, even though propriety stated that she ought to have let it go once they sat down. ‘I can tell you from personal experience that she is a formidable foe.'

She pulled off her long white glove and pointed to several thin, small scars on her arm. ‘These are all marks from her claws.'

Before he knew what he was doing, he ran his thumb over the little ridges of skin. ‘Really?'

Helen's breath caught. ‘Truly. However, it would be remiss of me not to mention that I have marked her in several places as well. There's no creature quite as vicious, or as loving, as a sister.'

‘Then I am glad that I do not have any.'

She nudged him with her elbow. ‘Oh, but you are deprived. Sisters are the best friends you could have in the world. I miss my little sister, Becca, cruelly.'

‘Was she too young to come to London?'

Helen slumped in her seat, her lower lip coming out slightly in a seductive pout. ‘No. I was too badly behaved.'

‘I am sure that is not the case.'

Sighing, she shook her head. ‘No. It really is. There's a secret passageway behind the family rooms, where Becca and I eavesdrop on my parents' conversations. Mama wouldn't let Becca come because she said that a pair of Bow Street Runners couldn't keep track of us together in London.'

Mark tried to hold it in, but he couldn't help himself. He laughed. After nearly two years of no humour, he found that he couldn't help but laugh in Helen's company. At her words. Her antics. Her beauty.

Helen sat up straight and released her hold on his arm.

Glancing over his shoulder, he saw that the Duchess of Hampford was coming. She was a tall, imposing woman in dark purple, wearing a king's ransom of diamonds around her neck, ears, wrists, and a tiara in her hair.

‘Lord Inverness, I am delighted to welcome you to our house. It appears that Helen has already made you feel at home.'

Mark struggled for a moment to get to his feet, before bowing to her. He hated when he wobbled on his wooden leg. ‘Thank you for the invitation.'

‘You mean her summons?' Helen said, with her sharp wit and even sharper smile.

The Duchess of Hampford gave her daughter a glittering smile.

Mark felt an almost overwhelming curiosity to meet the young man who had caught Helen's heart. The only thing he knew was that the curate's temper was amiable, unlike his own mercurial disposition. And he was not still fighting a battle that was long over.

Sighing, Mark thought he had once been animated and amiable in company. Sometimes he thought that he'd left more than his leg in Brussels—that he'd left behind part of his personality. But it was hard to constantly be jolly when one was in constant pain.

The Duchess waved her fan. ‘Why don't you both come say hello to Lady Glencannon and her son, Lord Watford. She is your aunt, I believe?'

‘My late father's sister.'

Mark offered his arm and suppressed a smile as he watched Helen roll her eyes. ‘I hope that you don't have any spiders on your person. I should hate for them to accidentally end up on me, instead of my cousin.'

Helen briefly tightened her hand on his arm. ‘Alas, no. But I have been collecting them since I've arrived in London. I have thirty-six of them saved in my glass jar.'

An involuntary shudder ran down his back. ‘Please say that you don't like mice as well as snakes.'

‘I don't. My little sister, Becca, is the one who loves rodents, but Theodosia makes sure that I don't have any in my room. Or even in the house. A snake is better than a cat at keeping down the mice.'

He chuckled. ‘I'll take your word on that.'

‘You can take more of my words than that,' Helen said, grinning at him. ‘My publisher sent a note over that I can overlook the pages before he does his final printing of my book. I shall take your sketches with me for the wood blocker to etch. I am so thrilled, I could roar like a lion.'

‘I would love more of your words.'

It was true. Mark couldn't help but grin back at her. He wanted to hear and keep all her words for himself.

His smile faltered as he bowed to his Aunt Glencannon. She was a Friday-faced woman with a long nose. Her dark hair was swept back from her head in a ruthless bun. Her figure was all sharp angles. His cousin, Watty, appeared even more at a disadvantage at her side as her foil.

Mark bowed to his aunt.

‘I don't know what your father would think of you,' Aunt Glencannon said—her voice had no trace of her Scottish accent or ancestry. ‘You haven't taken your place in the Parliament, nor in society.'

He felt Helen's hand tighten like a claw on his arm. ‘Yes, my father and grandfather both served in Parliament.'

His aunt gave him a hawklike stare and he realised how much she resembled one with the plumage in her hair. ‘Your elder brother also was remiss in his government responsibilities. He didn't come to London once after your father died.'

Mark couldn't blame him. He'd be running to Scotland right now if his wooden leg could carry him. ‘I shall do my best in future, Aunt Glencannon.'

‘Good. Your King is in London.'

Helen cleared her throat, her talon-like hold on him tightening. ‘Actually, he's not. Mad King George is at Windsor Castle with his daughters. The Prince Regent himself told me at my coming-out ball.'

Mark wanted to chuckle again when he saw the look of indignation on his aunt's sullen countenance.

‘How dare you speak of your King with so little respect?'

Helen tipped her chin. ‘I am the daughter of a duke. I can do, or say, whatever I dashed well please. Besides, there is no love lost between the Prince Regent and his parents. He has been my mother's dear friend for decades.'

Aunt Glencannon brought a hand to her mouth. ‘Well, I say!'

‘What do you say precisely?' Helen countered impertinently.

Mark needed to intervene before an argument could erupt between the two ladies. ‘Aunt Glencannon, forgive me. I should have introduced you to Lady Helen at the first. Lady Helen, allow me to introduce you to Lady Glencannon. Her son you already know—Lord Watford.'

Watty gave Helen an oily smile and took her proffered hand. He bowed over it and then kissed it. Helen tugged her hand back mid-kiss and his cousin's face turned a blotchy red.

Helen curtsied to his aunt.

She gave her only a cold nod in return. ‘It is a good thing that you have a large dowry, girl, otherwise no man in his right mind would give you a second glance. You are too thin and bad tempered.'

Instinctively, Mark took Helen's elbow. He had no doubt that she could hold her own in a cat fight, but the parlour was hardly the time or place. He pulled her away from his aunt and cousin over to a man who had to be Helen's brother. He had the same lanky frame, fair hair and light blue eyes.

‘Didn't fancy a brawl, Inverness? I was about to offer ten-to-one odds on our Helen here. I have seen her hold her own against opponents twice her size.'

Helen stomped on her brother's foot. ‘Mark, this is my annoying brother Matthew.'

He gasped in pain and rubbed his sore foot. ‘Dash it, Helen. How can you even make it hurt in only dancing slippers?'

Mark bowed his head. ‘A pleasure to meet you, Lord Matthew.'

‘I'm actually the Earl of Trentham,' Matthew said, a wry smile cast at his sister. ‘It's all hush-hush. But my wife caught a French spy and his British government counterpart, so, of course, being a man, I took all of the credit and the title.'

Helen smirked. ‘Nancy said you helped a little at the end. A very little.'

Her brother grinned. ‘How generous of her. I did nothing but stand there and hope for the best.'

Helen looked around the room. ‘Where is Nancy tonight?'

Matthew, Lord Trentham, looked at Mark. ‘I am afraid that my wife wished to be here and add her familial pressure to the match that neither you nor Helen wish for. But, alas, she is indisposed.'

Mark wasn't as opposed to a match as he ought to have been.

‘Is she still vomiting?' Helen asked.

Matthew nodded, his face a little green. ‘She got dressed to come for the dinner, but after the third bowl was required, she thought it best to stay at home.'

Shaking her head, Helen sighed. ‘Poor thing. She's expecting another baby and is having a terrible time of it.'

Mark had never before been interested in other people's children, but after seeing the Duke dote on his son, he was. ‘Do you already have a son and heir, Lord Trentham?'

‘Something much better. A daughter. My only real contribution to the world. And again, my wife did all the work and I get the credit.'

‘I hope Nancy has another girl. We have quite enough boys in the family,' Helen said, then explained to Mark, ‘You already know Arthur. My brother Wick and his wife Louisa have three sons already and will be welcoming a fourth child any day now. And Mantheria only has a boy.'

Mark watched Matthew to see what he thought of another girl, instead of the required male heir to continue the title.

Lord Trentham nodded his head slightly. ‘I, too, have been praying for a girl, but if the baby is a boy we will still endeavour to love him as well.'

Mark snorted in surprise. Such words were usually reserved for female babies with a ‘good try, better luck next time'. But although they were jestingly said, Mark didn't doubt their sincerity. Matthew didn't care about providing an heir to his title or his name. Yet, having a son to continue the family line was ingrained in the British nobility and gentry. He remembered his father drilling it into his brother. And then his mother into him, after his brother's untimely death. But it seemed that the Stringhams loved their children for their own sakes and not for their place in the dynastic line.

‘I see Wick and Louisa coming in,' Matthew said. ‘They're always late, which means that Mama will be starting the promenade into the dining room. If I were a better man, Inverness, I would take Helen off your hands. But I'm not.'

Matthew strode away from them, before Helen's punch could land on his arm. He took his mother's elbow.

Helen huffed. ‘My brothers are such pests.'

Mark's own sibling had been the same. Oh, how he missed him. Missed having a family. He escorted Helen into dinner and there was no other place he wished to be. Mark was lucky enough to sit between the Duchess of Pelford and Helen. And far enough away from his aunt on the opposite side of the table that he would not be expected to make conversation with her. Or his cousin Watty.

Mark couldn't help but glance as the Duchess took off her long gloves and put them in her lap. She also had small white scars all over her arms. The Duchess caught him looking and he felt the blood rush to his face. He'd flirted with her when she was single and he didn't wish for her to think that he still admired her. Especially since he was more than half in love with her little sister Helen. Not that she wasn't a handsome and intimidating young woman.

She must have noticed him staring, for the Duchess held out her arm to him. ‘Yes, Helen gave me these scars. I dare say she showed you the ones I gave to her. Although it's impossible to tell which scratches are from each other and which ones were from our kittens. Helen unfairly claims they are all from me.'

‘ All the scratches on my arms are from both of you,' the Duke interjected, making everyone laugh. ‘I'll show you some time, Inverness. The Stringham girls were feral cats growing up. Even Becca scratched me once. She was the youngest kitten and the nicest of the bunch.'

Helen leaned forward to speak to Pelford past him. ‘Becca didn't want to be left out in torturing you.'

Pelford smiled. ‘I close my case. Feral cats.'

‘Oh, stop whining, Samuel,' his wife said. ‘I took a bullet for you and that scar is much worse than any of our scratches.'

Mark found himself leaning forward. ‘You were shot, Duchess?'

‘Yes. Samuel and I were scouting for information in France just before the Battle of Waterloo. We were attacked.' She touched the curve of her waist. ‘I was hit here... Not that I didn't get off a shot myself. I used to love to shoot. Not even Samuel could beat me in marksmanship. But now I cannot endure the noise of the bullets or the smell. They bring back too many memories of the battles and the bodies. I suppose it is little enough to sacrifice, since I was able to come home alive with Samuel.'

Mark used to love hunting with his father and brother, but now he could not. He also woke up gasping in the night, his nightshirt covered in sweat that felt like blood running down his head and back. But the worst part was that when he closed his eyes, he saw their faces. His Highlander men. The ones whom he had called friends who had died on the field. His leg cut off and piled on top of countless others to be burned. The smell of burning flesh was worse than gunpowder, but both were imprinted on his memory for ever.

‘My wife giving up her gun makes one less thing for me to worry about,' Pelford said fondly. ‘Now if she didn't make eyes at every fence she sees, my life would be just about perfect.'

Helen bumped her silverware. ‘Unfair, Samuel. When you're just as bad and horse-mad as she is.'

The Duke held up his hands. ‘You see what I grew up with? It's no wonder I have so many scars.'

He watched the Duchess elbow her husband. ‘You're about to get another.'

Mark laughed with Pelford and Helen. He'd almost forgot that there were other people at the large dining room table. The Duchess of Hampford sat at the head, her son, Lord Trentham, at the bottom. On her right side sat the Marquess and Marchioness of Cheswick, Sir Edward Monson, the Duchess of Glastonbury, Watty and his Aunt Glencannon. On the left, the Pelfords, himself, Helen, William Fitzgerald de Ros and Lady Georgiana Lennox. Georgy was quite his favourite cousin. She was the daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Richmond and still single, despite being two and twenty.

‘What, pray, is so amusing?' Aunt Glencannon asked in a voice loud enough for the entire table to hear.

Georgy cleared her throat, smiling. ‘My dear friend Frederica is only teasing her husband, Aunt.'

His aunt gave a dismissive sniff. Clearly, happiness in marriage was something to be frowned upon. His parents' marriage had certainly been unhappy, even though his father had defied his family's expectations and married the daughter of a wealthy Scottish mill owner. Whatever love they'd once shared had been long spent by the time Mark came along. All that was left of their relationship was his mother's fortune, which allowed his father to live the life of an aristocrat. He had seen that Mark and his brother were educated at Eton and then Oxford. But aside from that, he'd spent nearly half of every year in England, without his family, and had little to do with either of his Scottish sons.

‘Both the Duchesses were in Brussels during the Battle of Waterloo, Aunt Glencannon,' he explained. ‘It is because of their tender nursing ministrations and wonderful red soap that I am here today.'

Aunt Glencannon sniffed into her napkin, clearly unimpressed with their services. She had no idea how horrifying a hospital could be. Yet the two Duchesses had been as comfortable there as they were in a ballroom.

‘You forgot about me, Mark. I was there,' Georgy said, smiling.

He lifted his wine glass to her. ‘You were. Thank you for all that you did too, Georgy.'

‘Were you there as well, Lady Helen?' Aunt Glencannon asked, her hawklike eyebrows raised. ‘You are over one and twenty, are you not? Why is it that you were not presented until this year?'

Helen inhaled sharply, her nostrils flaring out. ‘It took longer to tame me than it does most young ladies. My parents decided to postpone my debut.'

‘It was my decision,' the Duchess of Hampford said, from the top of the table. ‘I do not see why we in the beau monde are in such a rush to get rid of our daughters. We do not expect our sons to marry at seventeen. My husband, as well, did not wish to be parted from our youngest children yet.'

Aunt Glencannon sniffed again. ‘It is different for young women. If they do not marry young, they grow too independent and do not become obedient wives. Besides, valuable breeding years are lost.'

His aunt gave Helen and then Georgy a glare. They were both over twenty and he didn't think either of them were particularly mouldable. Nor did they want to be considered as brood mares.

‘Men do not want obedient wives,' Mark said. ‘They want good companions.'

‘Only a crippled man would say such.'

Several of the ladies gasped at his aunt's words. The Duchess of Hampford signalled to the butler to have the footmen serve the next course.

Helen placed her hand, palm up, on his thigh underneath the table. He nearly jumped out of his seat and his heart thumped. At first, he thought that she was trying to give him comfort. But he realised when he saw the sad look in her eyes, she was seeking it. Covering her cold hand in his larger one, he held it tightly, eating the rest of the meal with only his left hand. If any of the Stringhams or his aunt noticed that he was only using one arm, they made no comment.

After dinner, they went to a beautiful blue drawing room where several card tables were laid out.

‘Lady Glencannon, Lord Watford,' the Duchess of Hampford said with a smile that appeared to be forced. ‘I insist that you make up a pair with myself and my son Matthew. I've heard that you are both excellent cardplayers.'

Matthew passed by Mark and Helen. ‘I'll fleece her for you and take you to Gunter's with the spoils.'

Helen giggled, before whispering in Mark's ear, ‘He will, too. Matthew can make money out of thin air.'

‘Come over here,' the Duchess of Pelford called to them. ‘You two can take us on in whist...and no cheating, Helen.'

They sat down at the table.

Helen picked up the deck of cards and shuffled it fast, turning the cards into a bridge. She handled them better than any professional gaming house worker he'd seen in action. ‘I don't always cheat.'

Pelford barked a laugh. ‘Yes, you do.'

Mark found himself laughing with the Pelfords at Helen's expense. The card table they'd chosen was about as far from his aunt Glencannon as you could be in the same room. A choice that he didn't think was a coincidence. He'd never been much of a cardplayer before, but he could tell that Helen loved the game. She played with great flare and ruthless precision.

Helen set down a card. ‘I trump your ace.'

And she had trumped him.

Completely.

Fullepub

Fullepub