Chapter Eight

S oon, it would be dark, and it was time to go back to the house. Pippa's father hadn't allowed her to have gas lights installed in the orangery. It wasn't worth it, he'd said. It was just a place for her alone.

She wasn't worth it to him.

But Wife Six, known to the rest of the Ton as Carolyn, had had an entire room converted to her dressing room with a daybed for her face massages. She thought frown lines came from a lack of care. In Pippa's opinion, this wife was the worst one yet and spread through the house like a disease. Room by room, she put her mark on the place and transformed the carefully selected decor that had been their family for generations into many vulgar arrangements. The bright pink curtains she had installed in the drawing room had orange fringes, and the new upholstered settees clashed in the brightest shade of rust red. It was hideous, especially considering the turquoise wallpaper that was partially faded, a leftover from the previous decor that donned shades of blue and white furniture. Wife Six had no decency, no taste, no scruples. But she had a goal: to get rid of Pippa.

And Pippa tried to stay out of her way.

That's why Pippa much preferred her orangery. It was a little house just outside the larger house. One might call it a doghouse for the unwanted daughter, but to Pippa, it was everything her mother had taught her about life. Every time her orchids had offshoots, she reveled in the beauty of the delicate blossoms; it was as if her mother breathed over her shoulder. Especially when the pineapple bore fruit, and she used the same knife with the wooden handle that her mother had kept hanging on a nail on one of the columns, she tasted the sweet and tangy love. For what else could these moments be called except for love? They were rare and precious and almost extinct these days.

By the time Bea found Pippa—not that it was difficult to guess where she'd hide—Pippa was a picture of agitation and had repotted the phalaenopsis orchids one by one. Her cousin, ever perceptive when it came to matters of the heart, quickly picked up on Pippa's distress.

"There was a man here, wasn't there?" Bea asked, her eyes narrowing as she sniffed. "It smells different. Smells like… musk and sandalwood but you don't grow any here."

Pippa nodded her cheeks uncharacteristically hot. "Yes, and he was absolutely infuriating," she admitted, her voice laced with frustration.

Her cousin's eyebrows lifted in surprise. "I've never seen you ruffled over a man before," she mused. "What happened?"

"He said…he implied that I was deficient ," Pippa confessed, wringing her hands anxiously in her lap.

"Deficient?" her cousin echoed, her voice sharp with disbelief. "Who was this man?"

"Nick," Pippa clarified, her voice wavering. He'd been on her mind so much; how couldn't Bea know who she meant? "To be more accurate, he suggested I had a deficiency ."

"And what might that be?" her cousin queried, her tone now soft with concern.

"Farsightedness," Pippa finally managed to utter.

"In the figurative sense," Bea said and put her hands on her hips. "He's right."

"He meant literally . As in, I need spectacles," Pippa corrected her.

The revelation appeared to give her cousin pause. She studied Pippa for a long moment, her gaze thoughtful as she processed this new information. The usually vibrant orangery was filled with a tense silence, the air heavy with unspoken thoughts and questions.

Finally, Bea spoke. "He has a point," she said.

A sense of dismayed betrayal rose in Pippa's heart. "No!"

Bea shrugged. "He does. It might explain why you are so clumsy."

"I'm not—" Well, she couldn't actually deny the truth of it. But she could try. Pippa took a deep breath before announcing, "I'm only clumsy at balls and in closed rooms."

"Yes, because you cannot orient yourself by seeing things far from you. But you have the keenest sense of direction in town; you always know where we need to go. Maybe that's because you can see at a distance."

"Oh!" That made more sense than Pippa cared to admit. Could it be true? Could her clumsiness be attributed to farsightedness? Was Nick correct about it being a condition and not a characteristic? She'd struggled with it for her entire life as a fault; it was hard to see it—so to speak—otherwise. "I suppose…well. He said he's an oculist. A doctor."

"Really?" Bea's voice rose in apparent intrigue. "What did he say you should do about it?"

"Come see him at his office, be fitted for eyeglasses." Pippa wrinkled her nose. She was missing a pair of glasses and a hat of whipped cream with a cherry on top so the Ton and her father's friends could make even more fun of her. "Glasses are not very flattering. I'll never catch a husband that way."

"But wouldn't it be nice to cure your clumsiness altogether? So, what if you wear glasses? They might make you look smart like a professor."

"I'm barely a professor; I'm just a girl." She frowned. "Besides, girls can't be professors. I'd be called a bluestocking!"

"Pish-posh," Bea scoffed. "Mark my words, one day, there will be girl professors for all sorts of things. You could lecture people on botany for hours. It's the perfect solution for you if it's not a man you want and just plants!"

"Except that I don't want a solution right now, not if it means I'll draw even more attention to myself with an ugly pair of spectacles."

"Nonsense. If all you need is eyeglasses, get them. If I were you, I wouldn't waste another minute. Do you know where to find him again?"

Pippa handed her cousin the card; she'd been carrying it with her, tucked in her sleeves, since he'd given it to her. Heavens forbid Wife Six or anyone find it among her things.

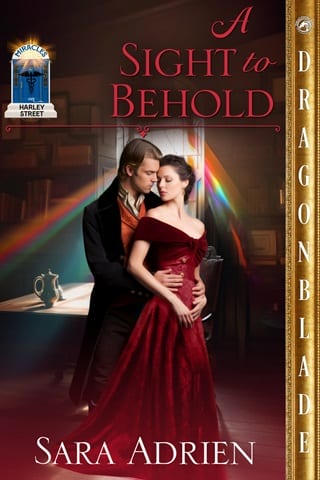

Nicholas Folsham

Oculist

87 Harley Street

"Go there first thing tomorrow morning!" Bea said.

Fullepub

Fullepub