Chapter 4

It was the light that drew so many artists to Cornwall. The great marine painter J. M. W. Turner had inaugurated the tradition. He'd toured the West Country at the beginning of the century, walking or riding the whole of the way, nearly as far as Land's End. The golden views he put to canvas inspired future generations, and the railway bridge made their treks west swifter and more comfortable. Now a dozen trains crossed the Tamar a day. You could chug out from Paddington Station in the morning and step off the Cornish Riviera in St. Ives in time to set up your easel and capture the sunset.

That's what Kit had done, two years ago. He'd sent his luggage to Tregenna Castle, the Great Western Railway hotel, and raced down to the foreshore of Porthminster Beach, wedging his easel between the seine boats, painting until it was too dark to see his brushstrokes.

He'd come for the light, like Turner, for the breathtaking natural beauty, for the scenes the local industry provided, fisherfolk at work.

He'd come for the chance to be himself, fully himself. To introduce himself as Kit Griffith to everyone he met. To hear himself called the same. To answer to it. To go months without hearing that other name, Kate Holroyd, the sound of which set his teeth on edge.

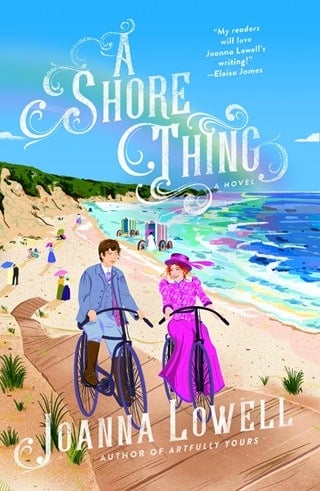

Riding away from the scene of that unexpectedly agreeable smashup, the wind in his hair, light streaming down from the sky and reflecting up from the sea—he could feel it again, the joy and ease, the sheer relief of those early days.

He'd begun to sign some of his pictures Kit Griffith long before St. Ives. Putting that masculine name to his work—it felt true, a way of expressing something about how he experienced the world he represented on those canvases. But he'd maintained a separation, in his mind, between Kit and Kate. Perhaps because he'd known society enforced such distinctions. Perhaps because he'd feared collapsing the tension, collapsing alter egos into one identity—the choice and additional sacrifice required.

He'd endured the irritation, the slight abrasion of wrongness, until the repeated chafing burned like fire.

Geography had offered a solution—all those miles between London and St. Ives. He could be Kit here, at the very edge of England. And Kate there, with his friends and his family. His friends at least accepted that Kate wore trousers, and his parents tolerated it as best they could.

They accepted and tolerated her.

He turned off the path, the Rover juddering, and pedaled over the heath, the smell of wild thyme rising from beneath his wheels. Miners' paths crisscrossed the land, and he picked one up and spun along, curving back toward the cliffs, until the huer's hut rose before him, round and gray.

Such huts dotted prominences on the Cornish coasts. From high above the harbor, huers watched for shoals of pilchards, sending up cries and directing the boats below to the glinting silver mass of fish.

He jumped off his bicycle and pushed it to the nearest boulder. He scrambled up the lichen-spangled granite and stood gazing out at the horizon, the blurred line where airy fathoms churned into the thicker blue of the Atlantic. Luggers with rust-brown sails drifted toward the bay.

Wind blew steadily, drying the sweat that had gathered under his collar. He spread his arms, coolness pooling in their hollows, then he probed the ridges of his brow, walking his fingers up to his hairline, smiling despite the painful tenderness.

Nothing like getting staggered by a beautiful woman. And what a woman.

Blunt and bossy, her coppery hair nearly metallic in the sun. That hair, and her strong profile, put him in mind of Roman statuary.

Muriel Pendrake looked like a goddess cast in bronze. If a goddess wore a scandalously short yachting dress with boys' shooting boots, tall and stout and coated in rubber.

She was an odd duck, bewitchingly outré. She'd been collecting seaweed with Raleigh, the sunburnt doctor. He should have guessed even before Raleigh had pointed to the jars in the basket. She'd smelled of rosemary soap, but also of the ocean, and her skirt was crusted with salt, and, then, by God, those boots.

He'd seek her out at the rock pools. He'd carry a picnic basket filled with scones and pots of raspberry jam and lemonade and Pimm's, to appease Raleigh. Then he'd whisk her away to a secluded cove where they could pursue any number of summer activities.

First, though, the joust.

He half climbed, half jumped down from the boulder and righted his bicycle.

That Deighton was a muttonhead, exactly the kind of entitled blighter he lived to vanquish. His old self—she had thrilled every time she'd asserted her presence in a place she'd been told she didn't belong. Every time she'd taken a medal for drawing, or run the table in billiards, or made some braggart shut his mouth.

Kit's impulses hadn't changed, even if his dearest friend—former friend—Lucy Coover, now the Duchess of Weston, refused to believe it. But his triumphs landed differently—they didn't undermine assumptions about female capabilities. They didn't blaze new trails. More often than not, they partook of the very privilege he'd once envisioned himself helping to dismantle.

For example, his solo exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery this past November. A tremendous critical success. The least picture went for twice the amount commanded by Kate Holroyd's best.

Had his painting so improved? Or did the Consulting Committee, the critics, the public value it higher by virtue of the signature, the abbreviated biography that played so neatly into societal myths about the solitary male genius?

People were keen to attribute visionary greatness to a mysterious young man. If you believed the gossip, even the reviews themselves, Kit Griffith's refusal to attend his own opening was as radical and interesting as his merging of form and color.

He'd allowed himself to relish the achievement regardless.

And then his life broke. Or rather, his two lives collided.

It had been Boxing Day, his third day back in town for the Christmas holiday. When he'd fulfilled his family obligations, he'd walked to Weston Hall, rare London snowflakes drifting down, whiter than gray for once, almost sparkling. Nose cold, blood hot, he'd taken stomping, twirling steps, had been laughing as he'd charged up the stairs to bang on Lucy's door. He'd been so excited to see her after his long absence, bursting with stories.

She'd confronted him with his exhibition catalogue, voice icier than a thousand winters.

Tell me this isn't you.

But it was. He couldn't deny it, and he couldn't find the words to explain. As students at the Royal Academy of Arts, he and Lucy had formed an artistic society, the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood. They'd exchanged praise and criticism at the easel. They'd entered into passionate collaboration with fellow artists—women artists—evolving new styles. They didn't exhibit behind each other's backs. They celebrated each milestone together, for what it meant for them, and for what it meant for women generally.

I can't believe you'd do such a thing. I can't believe you'd betray us all.

The ice in Lucy's voice traveled through his veins until it reached his heart.

He'd intended to stay in London until Twelfth Night. He could hardly remember the excuses he'd given his parents. The next morning, he was on the train out of the city.

Motion caught his eye. Two men were hailing him from the edge of the cliff, waving from behind their easels. Johannes Bernhard and Shigeki Takada.

Last summer, they'd drunk barrels of ale in each other's company and covered miles of canvas with paint. This summer, Kit was keeping his distance.

He waved back, but he was already rolling his bicycle in the opposite direction, hopping onto the saddle.

After that shattering confrontation with Lucy, he'd found himself unable to sustain focus on large pictures. He'd spent the late winter and spring dabbling, producing but a few small color sketches.

Until the fifteenth of May. That was when he'd finally written Lucy a letter, formally withdrawing from the Sisterhood.

I can no longer be your Sister,he'd written. But I hope to remain your friend.

He hadn't managed so much as a scribble since. For him, art was over.

He pedaled for home, where he could hide from all this goddamn painterly light.

Once home, he spent the remainder of the afternoon taking apart his best high wheeler—a New Rapid, the same model as Deighton's—and putting it back together, assuring himself that his mechanical steed was in peak condition. Reassembly complete, he considered decoration. For a joust, destriers wore rich caparisons embroidered with heraldic symbols. He could paint gold bezants on the black steel, to signal that he rode for Cornwall.

His fingers trembled, then closed into a fist. No, he wouldn't—couldn't—paint gold bezants, or anything at all.

His nails were cutting half-moons into his palms when a decisive knock made the door jump in its frame.

Muriel Pendrake's face appeared before him. He could feel the ghost of her kiss, butterfly soft. Her lips had opened beneath his. In that moment, she'd wanted more.

With a good rake, seduction had a tonic effect.

A low dose wasn't always sufficient.

He hoped she'd decided to follow the doctor's orders. That she'd come to find him. That she'd come for more.

He wiped at the grease on his hands with a rag.

The door jumped again.

His heart jumped too.

Florence,he'd say. I've been expecting you.

"Holroyd?" Another knock. "Blast. Sorry. Bungled it. Griffith, I mean. Griff, it's me."

The unmistakable voice sent Kit rocketing around his worktable. He flung open the door and stared, disbelieving, at the one old friend in the world he could greet without fear.

Fullepub

Fullepub