Chapter 20

"Behold!"

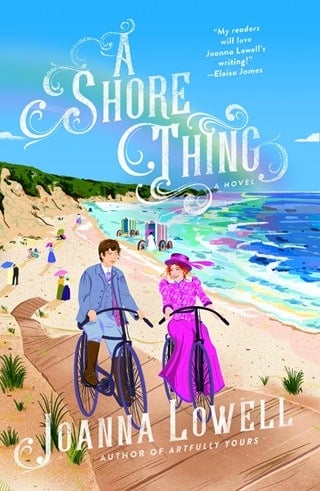

Griffith accelerated away from her, sprinting on his bicycle down the shady street.

"Behold what?" Muriel flew past primrose-covered villas, and out of the tunnel of elms, into the sunlight. He'd crossed a patch of grass and stopped to gaze down the steep slope at the shimmering blue of Falmouth Bay. He wore a crestfallen expression.

"The bay?" she asked, rolling up beside him. This was their first glimpse of it. They'd followed the coast around the Lizard, then swung inland at the Helford River, traveling the last miles to Falmouth through a verdant landscape of creeks and cornfields.

"It's picturesque," she offered. In his moody state, he was picturesque as well. Sulkiness did something unholy to his mouth. Warmth rushed through her, unrelated to the hours of continuous exercise.

Last night, that mouth had done unholy things to her.

She turned her flushed face into the breeze. "Is the inn nearby?"

He shook his head. "The inn's by the harbor."

"Then why are we here?"

"To hunt for seaweed on those rocks." He made a desultory gesture.

"Erm." She peered. The bay sloshed placidly below. "What rocks would those be?"

"Those magnificent, limpet-plastered rocks that you can't see because they're underwater." He knuckled a lock of hair off his forehead, pushing it under his cap with a grimace. "Falmouth has several beaches. Swanpool and Gyllyngvase are big and sandy and crawling with families. This one, which I swear to you exists—at low tide, anyway—is particularly interesting to algologists. Algologists? Bugger. Algologist is hard to say, even if you're not three sheets to the wind."

"You brought us here to hunt for seaweed." Suddenly, she was smiling, an over-wide, very silly smile. "What about the look on Deighton's face?"

"I will relish it when I see it." He shrugged. "But I realized I was far more eager to relish the look on your face. The look of delight when you beheld this…" The grimace returned. "This beach."

She couldn't contain herself. The boom of her laughter startled a seagull into flight. "You should see your own face. It's utterly forlorn."

"Is that so?" His brows lowered.

"Adorably forlorn," she revised, and his brows lowered further.

"You find my face funny." He leaned toward her, putting his face close to hers. "Or perhaps something is tickling the secret ticklish region of your body that I've mercifully made no attempt to locate."

"Is that a threat?" she whispered. Before he could answer, she was pitching herself off her bicycle. He lunged, and she shrieked and ran parallel to the bay, weaving around the daisies. He gained on her quickly, so she changed tack, bounding down the slope to the lapping waves. Here the bay hadn't swallowed the beach completely. She lurched along a narrow band of dry shingle, struggling to keep her footing. She heard his crunching steps, then his amused voice sounded in her ear.

"I thought you were nimble like a mountain goat."

"How nimble are you?" She gave him a shove. His arm shot out, and he tottered, swinging her with him. Her feet left the ground as they spun, locked together. When he set her down in the wet sand, he was laughing, staggering to keep his balance.

"I'm fabulously nimble." He wheezed. "If there were a candlestick, I'd jump right over." He jumped in place, sinking before he lifted up, and even then, barely leaving the ground.

"Hard to jump in sand," he muttered.

She rolled her eyes, then raced—nimbly—for the shingle as cool surf began to flow around her shoes. A moment later, he joined her.

She crouched to examine a shell, a peachy cowrie, no bigger than a fingertip.

"We could stroll," she suggested when she'd caught her breath. "See what we discover."

"Which way?"

She chose to walk toward the isthmus. He fell into step beside her, linking their elbows.

"No tickling," she warned him.

"Indeed not."

"I appreciate your forbearance." Her gaze glued itself to his gloved hand.

At dawn, she'd stirred and realized he was already awake, propped behind her, lazily stroking her hair. She'd slid her thighs together restlessly, unable to ask for what she wanted, until his calloused fingers had skated down her hip and worked the hard knot at the top of her opening, plunging inside as everything loosened, and cries burst from her lips.

"Self-preservation."

"Hmm?" She gave a little shake, looking up.

"It's self-preservation, not forbearance," he said wryly. "I know when I've met my match."

The light playing on his irises turned them to liquid silver.

On a shaky breath, she faced forward. The isthmus rose precipitously from the sun-spangled water, rock transitioning to wooded hillside. A castle stood on the hills' summit, like something from a fairy tale.

"Camelot," she murmured, half-dreamily, half in jest.

"A popular artistic subject," he remarked, after a pause. His voice was mild, but his biceps had tensed, and his stride changed rhythm.

"One of yours?" She stole a sidelong look at his profile.

"Oh, yes. The artists I grew up admiring painted knights and enchantresses. I had to try my hand at it."

"And?"

"I am half sick of shadows," he said, in a manner she recognized, from James.

"You're quoting. From a poem?"

"By Tennyson. ‘The Lady of Shalott.' Do you know it? The Lady is imprisoned in a tower, forbidden to look on Camelot directly. She must sit and weave the scenes she sees in her mirror. Eventually, she rebels. The reflected sight of a pair of lovers stirs her, and then Lancelot, who rides by on a warhorse. She leaves her loom. She leaves her tower. And for that, she dies."

"Golly." Muriel directed her frown at the castle. "You painted the unfortunate Lady?"

"I did a whole series. The Pre-Raphaelites all made drawings of her. In their illustrations, she's powerless by her loom, or floating dead in the river. I took more liberties with the poem."

"I am sick to the back teeth of shadows." Muriel tipped her head. "I'd like it if the Lady said something emphatic, then galloped away on Lancelot's warhorse."

"You'd have liked my pictures, then."

"I've no doubt of that."

The silence between them felt warm and comfortable.

"The Pre-Raphaelites," she ventured. "I've heard of them."

"From people telling you that you look like you belong in one of their paintings?"

That was it, exactly.

She flushed. "Also, I've seen Ophelia, by Millais. He's a Pre-Raphaelite, isn't he?"

"One of the founders of the Brotherhood."

"It's an extraordinary picture, botanically speaking. I could have looked at the riverbank all day. The plant life seemed infinitely detailed." Her brow puckered. "Of course, there was death at the center of the thing. Another floating woman. Do I detect a theme?" She paused. "And does something about me suggest a watery grave?"

"It's your hair." He slanted a gaze at her. "The women in their paintings have long, thick, wavy hair, often red."

"My hair isn't red," she sputtered. "Have you ever looked at me?" She shut her eyes. "What color are my eyes?"

"Your hair gives off a reddish glimmer."

"My eyes."

"Brown. With a belligerent glimmer."

She opened them and blinked away the sparkles. The afternoon air had a dazzling clarity.

"What about my eyes?" He bent over her, batting his lashes. She laughed and was still laughing when she intercepted his kiss.

How did he know how to kiss like that? Like casting a spell and issuing an invitation. The buzzing was in her ears, not bees—every particle of her being, rearranging.

"Your eyes are also brown, are they not?" Her breath hitched as they stepped apart, ruining her delivery.

He raised an ironic brow. "It seems you are no close observer of my person. Shall I come closer still?" He moved toward her.

She skipped back, scandalized, and as happy as she'd ever been. "We're abroad, in daylight."

"We are," he conceded, glancing about the deserted shore. "Quite correct." He halted on the approach and held out his arm.

They began to walk again toward the castle.

"It occurs to me," he said. "You can see my Lady of Shalott, if you're inclined. Several of my Arthurian paintings sold to an American dry goods magnate with a private gallery on Fifth Avenue. I've heard he puts on excellent exhibitions."

She felt a bittersweet rush of emotion. Months from now, she might stand in a great gilded room, surrounded by strangers, and look upon pictures that recalled her to this golden afternoon.

"I'll make it a point to attend."

"How long will you stay in New York?" He sounded nonchalant.

"Indefinitely." She gave him a bright smile. "I'm going to teach botany at an academy for women."

"Wonderful," he murmured, with undoubtable sincerity. "And you have friends there?"

She looked away. Friends overstated it. "Fellow botanists. We write to each other and exchange our findings. I became friendly with the Satterlee sisters when they were researching in England. They founded the academy. They're the ones who arranged for my position." She looked back at him. "And the ones who set up my original lecture at Clinton Hall."

He nodded slowly. "What do they think of that fellow's meddling?"

Good question.

"I don't know. I haven't had a letter since it happened." She stopped walking and slipped her arm from his. "They're members of his botanical society—the Heywood Botanical Society. It's the most important botanical society in the whole United States. They depend on his connections for their fundraising. They've been equipping a lab, modeled on the Balfour Biological Laboratory for Women at Cambridge. It's an expensive project. Whatever they think, they're probably best advised to keep it to themselves."

Griffith's forehead creased as though he meant to object.

She turned to the bay. "They look like chicken coops."

He turned as well and tracked her gaze. "Bathing machines?"

A lone bathing machine stood a few yards away, a wooden hut on wheels, the waves washing nearly as high as the hubs.

He shook his head, a smile flitting across his lips.

"What?" She crossed her arms. "I know that look." Her cheeks scalded. "Good Lord. In a bathing machine? Really?"

"Penny." He widened his eyes. "Your mind goes to such places."

"I'm wrong?"

He sighed.

"What was her name?"

He turned his gaze up to the clouds. "Becky."

She snorted, and he dropped his gaze to her face, amused.

"I was thirteen," he said. "My family was on holiday in Ramsgate. She and I went into the bathing machine together."

Muriel's eyes wandered back to the bathing machine in front of them. Anything could go on inside those dark, hot little changing rooms, even in the middle of a crowded beach, with no one the wiser.

She gripped her elbows. "Pray continue."

"We'd only met the day before, but we were already in love. Well, puppy love." He laughed. "We changed into our bathing costumes in a white heat, to make the most of the time, the three jostling minutes it took for the horse to tow us past the breakers. No opportunity had ever been so perfect. Maybe it was too perfect. For some reason, I couldn't kiss her. I froze completely. She waited for as long as possible. Our driver began to shout, so she opened the door and jumped into the sea, without a backward glance. That was it. From then on, she avoided me like the plague."

She looked at him, trying to gauge his seriousness. "Did you mind dreadfully?"

"My suffering lasted about as long as our love. It was a bad day and a half." He shrugged. "I was a bit callow back then. Anyway, we weren't meant to be."

"Too perfect," she mused, eyes back on the bathing machine. Her heart began to race. "What would you say to another chance at perfection?"

Kit didn't take her meaning. It wasn't until she marched into the surf, casting a teasing glance over her shoulder, that the penny dropped.

He pursued her, then, with all deliberate speed, waves pushing against his shins.

Inside the bathing machine, he turned to pull the shore-facing door closed, and to pull off his leather gloves, which he rolled tightly together, one inside the other, and tucked beneath the waistband of his knickerbockers, into the pocket sewn into the front of his drawers.

When he turned to Muriel, he could hear his blood rushing through his veins. The space was small, and hot, and dim, and smelled of old sun-warmed wood. She was standing with her back to the other door, her hat in her hands, stray wisps of hair framing her face. She looked equal parts eager and nervous. The hat went around and around, the brim rotating through her fingers. The tip of her tongue swept the inner rim of her lower lip, leaving it damp.

"Becky could have kissed you," she said, voice sounding oddly hushed in the little room.

He stretched up his arms and put his palms on the rough wood boards of the ceiling. "Neither of us thought of that."

"Why not?"

He dropped his arms. "We were thirteen."

She nodded as her dark gaze assessed him.

"You're thinking something," he murmured.

Carefully, she hung her hat on one of the hooks in the wall, lingering a beat too long. With a sharp breath, she faced him. Two steps, and she launched into his arms. The impact knocked him back against the door, which held, thank God, and both of her gloved hands pressed hard on his nape. She dragged his head down, thrusting up onto her toes. Her lips crushed against his, slightly off-center, wet heat at the corner of his mouth, and then she corrected, her tongue stroking inside. It was the clumsiest, most arousing kiss of his life. He half laughed, half groaned, and let her plunder him. She seeped into all his senses, the taste and the feel of her inseparable from the breathy sounds, the indefinably sweet scent. He kept his need leashed, until her teeth scraped his bottom lip, and he reacted, pushing forward, fusing their mouths.

The atmosphere changed around them. The heat thickened. Time slowed. His fingertips glided over her silky cheekbones, her sweat-glazed throat. Her convulsive gasp shuddered something loose inside him. He dropped onto one of the changing benches, pulling her down, gripping her bottom as she straddled his thighs, skirts bunching.

"You're thinking something," she gasped. Her eyes were wide and dazed, her mouth glistening.

"I'm thinking I'm glad I'm not thirteen," he said, and hitched her higher. A little cry escaped her, and he knew she could feel the bulge of his rolled gloves between her legs. He could feel it too, rubbing his groin as she rocked her hips.

"What is that?" she panted.

"Something to please us." He flexed, driving up, and she moaned and ground harder against him. "Do you feel pleased?"

"I could be more pleased." She struggled for breath, twining her arms around his neck, a smile stealing across her lips.

"Is that a challenge?" He bloody well hoped so. "What if I please you more?" He flexed again, muscles hard as adamant. She sighed, eyes fluttering closed. "And more?"

She kissed him, a voluptuous, open-mouthed kiss.

He broke away. "And more?"

Her forehead fell onto his shoulder, and she bore down, stroking herself back and forth, the friction between them discharging sparks. They both shuddered with it. He imagined tearing her bodice like paper, baring her completely and luxuriating in her flesh. Every contour. Every texture. But here, now, the layers of silk and cotton and woolen twill added to the pleasure. Seams and buttons bit at them, and that pleasing leather dragged sensation from him to her, and her to him. His climax hit him like a storm. He jolted and gave a guttural shout, and she stiffened, inner thighs clamping hard enough to bruise. When she'd shivered and slumped, he lazed with her on his lap, arm under her skirt, fingers caressing the downy skin above her garters. The pad of his thumb traveled up and circled, moving in time with her slow, extravagant pulses.

Clouds of lust still billowed in his brain. He let his eyelids droop, memorizing her shape, the feel and weight of her. He'd sat up half the night at the table, looking at her, and looking at his sketchbook—the paper dry despite the sodden clothing at the top of his knapsack, which he'd laid out by the fire. The marks he'd finally made were depressingly inadequate. The room had been low-lit, and he'd tried to rely on shading. He'd focused on her hair spread in shining ripples on the pillow—to no avail. He'd thrummed with the urge—the old urge—to draw, to paint, to express what he saw and felt in the visual language he'd studied for more than half his life. She was naked in the bed, all lines and curves and rich tones, her strong features languid, and he knew exactly how to translate the dreamlike moment, how to compose it, how to give it depth.

And he could not. He could not.

He'd guided them to Castle Beach, steeled for another confrontation with the page. He wasn't sorry that it would wait for another day.

She seemed to sense that his mood had shifted. She brushed her lips across his neck, and then her tongue coaxed his attention back to the present.

By the harbor, Falmouth bustled, streets choked with sailors. The inn was a dingy building sandwiched between an ironmonger's and a ship chandler's, the windows of the latter papered with advertisements in half a dozen languages. He locked their bicycles in the back courtyard, then they entered the inn itself, a warren of darkly paneled corridors and dusty rooms that gave off the warm, yeasty smell of old beer. As Muriel inspected the display of model boats, he rang the ship's bell by the desk and inquired after rooms. The proprietor didn't have their names in his register. Deighton actually presumed they'd thrown in the sponge. With a suppressed snort, Kit made a reservation—two rooms, for appearance's sake. One last rotation through the inn confirmed that the wheelmen were elsewhere.

Elsewhere seemed a good place to be. He and Muriel wandered back out into the town. They ate pilau at a curry house near the quay, then wound their way to the shops. Muriel found a drapery that sold dresses off the rack and stopped to make a purchase. He bought Valencia oranges from a grocer, and they continued on with their parcels, circling back toward the harbor, or so he surmised from the increasingly potent odor of tar and rotten fish.

When the water came into view, Deighton came into view as well. He was a head taller than the men surrounding him, and so Kit had ample opportunity to observe his darkening expression as their gazes clashed.

"Oh dear," murmured Muriel.

A small crowd had gathered around a post upon which two men had planted their elbows. One was Kemble. The other was a thickset sailor in a scarlet cap. It took a moment to realize the wrestling had begun, they were both so still and silent. Kemble's veins made a bulging map on his forehead. The sailor's lips had peeled back.

Deighton cracked his neck as Kit and Muriel approached.

"Here you are, then," he said.

"Here we are." Kit smiled.

"Use your legs!" shouted Butterfield. "Damn it all, use your legs!"

"I don't know that you rode all the way south." Deighton's blue eyes looked hard as glass. "You might have cut east early."

"Orange?" asked Kit, plucking one from the bag.

"Yes, please," said Egg, reaching around from behind Deighton.

"Mrs. Pendrake!" Prescott had turned from the combatants. "Mr. Griffith," he added, in a more subdued tone.

"It's mandatory that you ride the entire distance," persisted Deighton.

"Check our cyclometers." Kit shrugged.

"You might have tampered with them."

Patience.With Deighton, patience came at a premium.

"We rode the entire distance," he said. "If my word doesn't suffice, you can examine the page I took from the register at the Top House Inn." He'd offered the puzzled innkeeper a pound to tear it out. "You'll trust your own signature, won't you?"

"Ingenious." Prescott looked impressed.

"He wasn't ingenious. He was ungentlemanly," Deighton snarled. "No one anticipates his word being doubted unless he's a liar and cheat."

"Or dealing with a liar and cheat," suggested Kit.

The crowd exploded into French-sounding hoots and hisses.

Kemble's arm had advanced by several inches.

"The hook!" shouted Butterfield. "Finish him with the hook!"

A laugh cut through the masculine uproar like bell song. It was a high, clear feminine laugh. Not Muriel's. She laughed like a flock of adorable geese.

He looked over his shoulder. A woman was gliding toward them. A dark-haired, flower-faced woman in a heavily trimmed biscuit-colored silk gown, with an underskirt of dusky rose.

Grace Swanwick, the diamond of the West End sapphists.

Fullepub

Fullepub