Chapter Thirteen

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

T he song was still nibbling at Sally Blow.

She enjoyed working in the grocer’s shop up the road from the Bricklayers Arms. She’d come in early and sweep out while Mrs Parsons had her breakfast, then be busy all day weighing up the fruits and vegetables, twisting the paper bags full of beans and radishes, and on Fridays Mrs P. would give her a good deal on anything that looked as if it wouldn’t last over the weekend.

When she had come in that Tuesday morning, though, Mrs Parsons seemed much less disposed to chat than usual. Sally wondered if the increasing chill was making her rheumatism flare, so she’d shrugged her shoulders, taken her apron from the hook on the back of the door and got busy with the broom. She needed to keep busy, what with the song bothering her, and then Mr Sharps had turned up again on Friday night at the Bricklayers Arms and he, without doing anything, bothered her too. He’d arrived half an hour before she started and left again after her last song, when the crowd were still clapping. Every time his eyes rested on her she got a chill in her bones.

It was only at the end of the day, after the factories had let out and the girls who worked in the mill had been through, picking up odds and ends for their suppers, that Mrs Parsons cleared her throat.

‘Come into the kitchen, Sally. Have a cup of tea.’

Sally had hardly ever been into the kitchen. For the most part, she had her bread and cheese at lunch in the storeroom, among the bags of flour and sugar. Mrs Parsons liked to keep her privacy, so there was something in the air.

Mrs Parsons poured, and pushed the cup and saucer towards her.

‘Sally, dear,’ she said, ‘you’ve been ever such a good worker.’

Sally’s stomach flipped. ‘Thank you, Mrs Parsons.’

‘So this pains me,’ Mrs Parsons went on, her eyes fixed on a little ceramic donkey on the mantelpiece over the range. ‘My sister’s daughter needs work, and I can’t afford two girls.’

‘Oh,’ Sally said.

‘I doubt she’ll be as good as you.’

‘Don’t hire her, then!’ Sally said quickly. Her eyes were getting all hot. Mrs Parsons reached out and patted her hand.

‘She’s family, dear. You know how it is.’

‘Can’t say as I do, Mrs Parsons,’ Sally said, staring at the pattern on her teacup. ‘My boy is the only family I’ve got. And he’s six, so not much good at getting me employment.’

‘Now, Sally,’ Mrs Parsons replied, her voice getting firm. ‘Like I said, you’re a good worker. You’ll have no problem getting another job.’

The injustice of it made her skin hot. ‘Easy for you to say, Mrs Parsons. I was down to my last shilling when I met Belle and Alfred. I’m only just feeling like I’m back on my feet.’

Mrs Parsons withdrew her hand, and folded it together with her other one on her lap. ‘I’m sorry to hear that. But it cannot be avoided. Susan will be starting tomorrow morning.’

‘Tomorrow?’

‘No use hanging around when there’s a decision to be made.’ Mrs Parsons stood up quickly and fetched an envelope from behind the clock. Sally recognised her own name carefully written on it, though her vision was getting a bit blurry. She blinked hard. Mrs Parsons handed the envelope to her. ‘Now, there’s a ten-shilling note in there, as well as a reference saying you’re honest and hardworking.’

Sally took it and looked up at Mrs Parsons. Her eyes looked a bit red, too. Sally thought of her little store of savings, her attic room and her yellow curtains, her mending basket and the heavy old bed where she and Dougie could curl up through the winter and make up stories. If she couldn’t get another job – and sharpish – how long would Belle and Alfred let her stay there? A thousand recriminations leapt to her lips. What was the good of working hard, of showing some loyalty and pluck, if it could all be whipped out from under you in a second? But what was the point? Every time life let you get a bit comfortable, it sneaked up in your blind spot and swept your legs out from under you. A couple of weeks before she’d been admiring her curtains, and now she was thinking how long it would be before she had to pawn them for rent or Dougie’s medicine. She felt her breath catch.

‘Thank you, Mrs Parsons.’

She stood up, carefully took off her apron and laid it gently over the back of the chair. Mrs Parsons’ nose twitched. Perhaps she had been hoping Sally would make a fuss. That way, she wouldn’t feel so bad.

Sally let her shoulders droop, picked up the envelope and turned towards the door with a sigh. She’d bite back the words, but she wasn’t above twisting Mrs Parsons’ conscience a bit. Not that it was an act, either. She’d never been let go before, and losing a job – even if it was to Mrs Parsons’ niece – felt like a failure, as if she was being judged and found wanting.

‘Sally!’ Mrs Parsons said, getting to her feet. ‘Would you clean? My cousin is looking for someone to char.’ She looked guilty. ‘It’s not as pleasant as shop work, I know, but it’s better than the mill or laundry.’

It was a straw. Sally clutched at it.

‘I’m not too proud to clean, Mrs Parsons.’

‘Well, go along and see her. Mrs Briggs at The Empire.’

The Empire. What a turn-up.

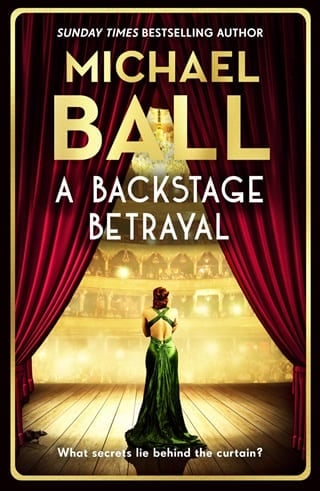

Sally dropped her eyes to the envelope in her hand and she thought of that night behind the velvet rope, watching the great and good arrive at the theatre and imagining herself in one of those sleek cars, pulling up to the red carpet, stepping out in an evening gown to the sound of popping flash bulbs and people calling her name. Now here was reality, coming to give her another nip. She’d go to The Empire, but in an apron, not a silk dress, and go in through the side door and be greeted with a grunt. If she ever got on stage, it would be to sweep up the flowers thrown at the real performers. Well, there you are.

Chin up, Sally Blow.

She straightened up and turned, her hand on her hip. ‘Thank you for the tea, Mrs Parsons,’ she said, ‘and for the tip. I’ll take it. But I hope you’ll miss me and your niece spills the sugar at least once.’

Fullepub

Fullepub